The 12th-century tower of St Rule (St Regulus), in the grounds of St Andrews Cathedral.

While many of these and other dramatisations dress themselves in the lavish costumes, scene-dressing and CGI that are the hallmarks of the so-called “sexy historical”, the content is often much less glamorous. The main focus of the discussion revolved around the prevalence and degrees of vice, debauchery and violence (including sexual violence) depicted in these programmes, their portrayal of women, and the ways in which they make use of the commonly held belief that the Middle Ages were a period in which life was “nasty, brutish and short”.

Clearly this is a very skewed and limited vision of the period, and yet it seems to be one that the US-based cable networks such as HBO, Showtime and Starz, who commission and in large part fund these series, have hit upon as a means of drawing in viewers. A similar formula can also be found in the treatments afforded to The Tudors and The Borgias. Why is it that this recipe has recently found success, and should we be concerned that the Middle Ages are getting such a bad press?

It should be noted that this new brand of “dirty medievalism” is, by and large, the preserve of the cable channels. Indeed in the UK, the BBC’s dramatic uses of the Middle Ages have tended to be oriented more towards family entertainment, with series such as Merlin and Robin Hood offering a very different depiction of medieval life: one that is gentler and interspersed with humour. Which of the two approaches, if either, presents a better reflection of the medieval reality?

St Andrews Castle (foreground), with West Sands Beach and the North Sea beyond.

Nevertheless, I’d hope that readers of my novels come away with the sense that kinship, duty and love did matter to medieval people, just as they matter to Tancred and his allies, and that there was honour to be found in their world. While treachery, backstabbing, power games and violence abounded, it seems strange to argue that these facets were peculiar to the Middle Ages, or that they were the main distinguishing features of that period. For that reason, as entertaining as these recent TV dramatisations are, there remains for some a nagging sense that, in limiting their vision, they do the Middle Ages a disservice.

Needless to say it was a fascinating discussion – one of many over the course of the conference. Even now, more than a week after coming back, I’m still working my way through and absorbing the various notes I made. I hope to share some more of my findings from my time in St Andrews in the not too distant future!

If you missed it last week, catch up with Part One of my report from “The Middle Ages in the Modern World”.

Based on real-life events, Sworn Sword tells the story of the great rebellions that swept England in the years after 1066, as seen through the eyes of a Norman knight named Tancred, who seeks vengeance after his lord is killed by English rebels.

Published by Sourcebooks Landmark, it’ll be available from all good bookstores and, of course, online as well, in both hardcover and eBook editions. Here’s the full synopsis:

January, 1069. Less than three years after the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and the death of the usurper, Harold Godwineson, two thousand Normans march in the depths of winter to subdue the troublesome province of Northumbria. Tancred a Dinant,a loyal and ambitious knight, is among them, hungry for battle, honor, silver, and land.

But at Durham, the Normans are ambushed in the streets by English rebels, and Tancred’s revered lord Robert de Commines is slain. Badly wounded, Tancred barely escapes with his own life. Bitterly determined to seek vengeance for his lord’s murder, the dauntless knight quickly becomes entrenched in secret dealings between a powerful Norman magnate and a shadow from the past.

As the Norman and English armies prepare to clash, Tancred uncovers a cunning plot that harks back to the day of Hastings itself. If successful, it threatens to destroy the entire conquest-and change the course of history.

This stunning debut sweeps readers into a ruthless, formidable world, where violent warriors seek honor in holy places and holy men seek glory in dark deeds. As the two opposing forces battle for conquest, the fate of England hangs in the balance.

Battles and betrayals abound, and there’s also a touch of romance, too – something, I hope, for everyone. And if that’s whetted your appetite, here’s the first chapter to give a further taste of what’s in store.

The ruins of St Andrews cathedral. At 119 metres (391 feet) in length, it’s the largest church ever to have been built in Scotland.

Being a historical novelist is all about bringing the past to life for a modern audience, so this conference seemed like the ideal chance to meet and share ideas with like-minded people from across the academic community who also happen to have the same love of the Middle Ages. And so I found myself in the company of 175 other delegates from 15 countries – some having travelled from as far afield as Australia, Korea and Canada – discussing how various aspects of the Middle Ages are represented today in literature, music, film, TV, climate change science and almost every other field imaginable.

I was there to deliver a paper entitled Representing the Middle Ages in Fiction, drawing upon my own experiences to discuss ways in which novelists might go about presenting their subjects in a historically responsible way. How rigorous should novelists be in their research? Can and should we hold them up to the same standards as professional historians? Accepting that a certain amount of invention and distortion is unavoidable in writing historical fiction, is there a certain point at which too much becomes unacceptable, and it descends into fantasy? What can historical fiction offer that non-fiction histories alone might ordinarily struggle to do?

The town of St Andrews, as seen from the top of the 12-century St Regulus’ Tower, which stands amidst the cathedral ruins.

I also had the good fortune to meet and discuss writing with Felicitas Hoppe, a German novelist and recent winner of the prestigious Georg Büchner Prize – one of the most prestigious German-language literary awards – who gave a plenary lecture about the challenges of adapting medieval romances into fiction. Other brilliant lectures included James Robinson from the National Museum of Scotland speaking about the similarities between the cults of medieval saints and those of modern celebrities; Bruce Holsinger from the University of Virginia talking about how an extract from the Icelandic sagas has found its way into debates about global warming; and Patrick Geary from the Institute of Advanced Study, Princeton, examining how medieval ideas of European ethnicity still have political currency today.

Those were just a few of the highlights from the conference. More on those, and on the rest of my findings from my time in St Andrews, in Part Two of my report, coming soon!

The Splintered Kingdom is released today in paperback in the UK, with a vibrant and striking new cover design! Look out for it in supermarkets and all good bookshops, as well as online. As always, e-book editions are also available on all platforms for the more technologically inclined.

Set one year on from the end of Sworn Sword, it once more features the knight Tancred, who has been rewarded for his exploits with a lordship on the turbulent Welsh Marches. But as the enemy stirs, his hard-fought gains are soon placed in peril. Under siege on all sides, the Norman realm begins to crumble, leading Tancred to face his sternest challenge yet. It will be either his chance for glory, or his undoing.

To whet your appetite for further Tancred adventures, the paperback edition also contains a sample chapter from the forthcoming third book in the Conquest series, which I can now reveal will be entitled Knights of the Hawk. There’ll be more info on where Tancred’s travels will be taking him next in the coming months.

Those of you who’ve been following this blog or have seen my updates on Twitter and Facebook will know that 14 March 2013 actually marks a double launch for the Aitcheson clan, as my brother Alistair’s eagerly anticipated new game for iPad, the fast and frantic Slamjet Stadium is also unleashed upon the world.It’s a huge amount of fun and has already been generating a lot of buzz in the gaming community. But don’t just take my word for it – give it a go yourself! It’s now available from the App Store across the world. For more details, including the trailer, visit the game’s official website.

Enter the date into your diaries! Thursday 14th March marks a mega-launch day for the Aitcheson clan. Not only will the paperback edition of The Splintered Kingdom be hitting the shelves – available in all good bookshops, supermarkets and online – but also my brother Alistair’s latest game for iPad, the fast and frantic Slamjet Stadium will be unleashed upon the world.

Set in the distant future, Slamjet Stadium features a galaxy of sporting stars drawn from the furthest reaches of known space to take part in the ultra-competitive and deadly Slamjet Tournament. There can only be one winner, and the only rule is that there are no rules!

Having already played the pre-release version of the game, I can tell you that it’s not just brilliant fun, it’s also incredibly addictive. Check out for yourself what’s in store, in this sneak preview:

Here’s what Alistair himself has to say about the game:

Based on an ancient 20th Century sport known as “football”, the Slamjet tournament is the hottest event of the galactic calendar. Arenas are filled with deadly saws, mysterious wormholes and ridiculous power-ups, and only the fastest and toughest can win!

Played on a shared iPad, players are free to get in each other’s way, steal each other’s characters or set off traps to mess their opponent up. It’s fast, it’s chaotic and breaking the rules is encouraged!

You can get all the latest updates by following Alistair on Twitter, while more information about Slamjet Stadium can be found on the official website and also on Alistair’s development blog, which also features behind-the-scenes videos and articles on the making of the game.

Slamjet Stadium will be released worldwide on 14 March 2013, the same day as The Splintered Kingdom is published in the UK in paperback. Spread the word on Twitter with #AitchesonBrosLaunchDay!

One of the toughest challenges involved in writing about medieval warfare is that of describing what battle in that period was like: how it might have felt to be there, including not just the physical sensations but also the psychological and emotional. What would have been running through the combatants’ minds? What motivated and inspired men like my protagonist, Tancred, to take up arms in the first place, and what gave them the confidence to risk their lives in the fray? Was it for money or fame that they principally fought, in the name of God or one’s king, or (more probably) was it a combination of all of these things?

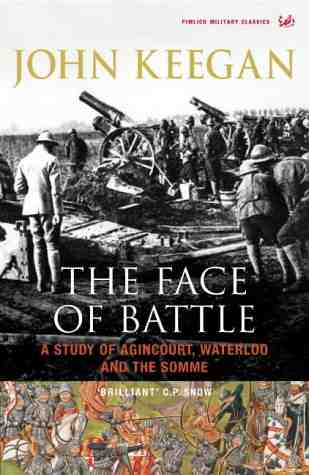

The historian John Keegan, who sadly passed away last year, explores similar themes in his pioneering book The Face of Battle, in which he analyses and compares the experience of combat in three major encounters of the last 600 years: Agincourt (1415), Waterloo (1815) and the Somme (1916). In particular he examines how the mechanics and logistics of conflict affected the psychology of the individual soldier – looking not just at the critical moments during the heat of combat, but also at the hours before battle was joined, and its aftermath once the dust has settled.

The historian John Keegan, who sadly passed away last year, explores similar themes in his pioneering book The Face of Battle, in which he analyses and compares the experience of combat in three major encounters of the last 600 years: Agincourt (1415), Waterloo (1815) and the Somme (1916). In particular he examines how the mechanics and logistics of conflict affected the psychology of the individual soldier – looking not just at the critical moments during the heat of combat, but also at the hours before battle was joined, and its aftermath once the dust has settled.

Keegan eschews analyses of strategy and tactics that many conventional military histories often involve, which – he argues – can sometimes misrepresent the ebb and flow of battle; instead he recognises the chaos and unpredictability inherent in war. The focus of his study is statedly not upon the respective generals and their abilities to lead and choose the correct course of action, but upon the lower ranks: a bottom-up rather than a top-down angle.

An advantage, too, of taking such a long view of the experience of battle is that he is able to highlight those aspects that have remained constant even over hundreds of years, in widely different fighting environments; and those which have altered as a result either of technological development – in weaponry, transport and communication, among other areas – or of societal changes.

A good example of the latter is the religiosity of the common soldier, which had declined during the age of the Enlightenment prior to Waterloo, only to re-establish itself in the Victorian age. The motivations of the men fighting in 1815 were thus vastly different to those of their counterparts only a century later. Prayer and faith in God helped many British soldiers combat their fears and reconcile themselves with the possibility of death in 1916, in a way and to an extent that their predecessors at Waterloo would not have been able to identify with, but which those at Agincourt very probably would.

One particularly ingenious feature of the book, which I can’t fail to mention, lies in the maps. Keegan juxtaposes the fields of battle firstly of Agincourt and Waterloo, and then of Waterloo and the Somme, depicting them on the same scale to demonstrate how the magnitude of battle has increased exponentially over the centuries.

Due to the outpouring of fiction in the military-historical sub-genre in the last couple of decades, accounts of past conflict illustrating the hardships and traumas faced by the front-line soldier are much more familiar than they once were. At the same time there has been a massive surge of interest in recent decades into the kind of bottom-up history favoured by Keegan: an interest that began in academia but which has filtered down into popular history as well, so that there has been an explosion in studies of this nature.

For both of those reasons The Face of Battle doesn’t seem quite quite as revolutionary a text as it probably did when it was first published in 1976. Nevertheless, it remains a thoroughly absorbing and eye-opening read, and one that I can highly recommend.