Earlier this year I was invited to do a Q&A with fellow historical novelist and Norman Conquest enthusiast Joanna Courtney over on her website, about the highs and lows of the writer’s life, the significance of 1066 and the appeal of historical fiction.

Earlier this year I was invited to do a Q&A with fellow historical novelist and Norman Conquest enthusiast Joanna Courtney over on her website, about the highs and lows of the writer’s life, the significance of 1066 and the appeal of historical fiction.

This week, to coincide with the publication of her latest novel, The Conqueror’s Queen, I’m delighted to return the favour, and Joanna has kindly written a guest blog post on seeing the events of the Conquest from a Norman perspective.

Joanna says:

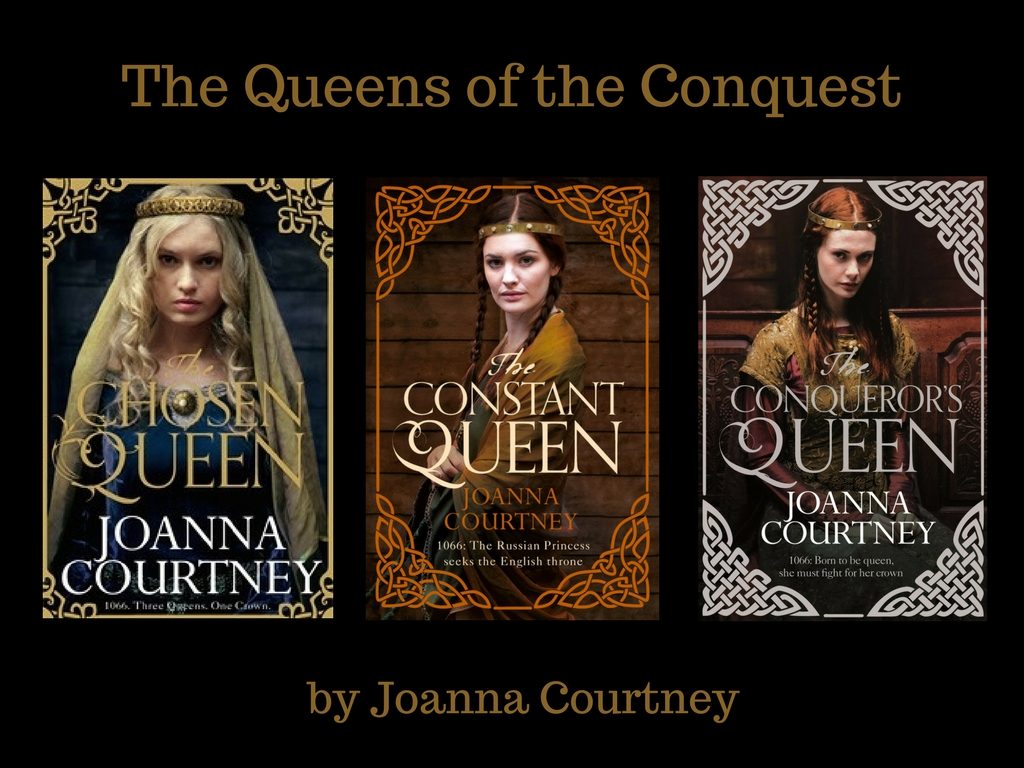

“Ever since I sat up in my cot with a book, I’ve wanted to be a writer. I started out with short stories and have had over 200 stories and serials published in women’s magazines, but I always wanted to make it as a novelist. I was delighted, therefore, when PanMacmillan bought my historical trilogy, The Queens of the Conquest, telling the stories of the too-long-neglected women of 1066. The Chosen Queen and The Constant Queen are both out in the world and it’s always my great joy to hear from readers who’ve enjoyed them, so I’m over the moon that The Conqueror’s Queen is just about to join them. I really hope people like the Norman side of the story and watch this space for more queens in the future…”

The girlie side of the Normans: or, understanding Duke William

Joanna Courtney

The Normans don’t get a great press in history. They generally go down as Vikings without the sex appeal – dour, straight-laced, humourless warriors who liked to go about nicking other people’s countries. Here in the UK they do particularly badly because of the terrible ‘Harrowing of the North’ after the Conquest in which thousands of men, women and children were wiped out in one of the greatest acts of genocide in known history. The Normans’ reputation is perhaps, then, fair…

But is it?

My novel The Conqueror’s Queen is the third in my series The Queens of the Conquest about the wives of the men fighting to be King of England in 1066. When writing the first two books from the Saxon and Viking perspectives I happily embraced the idea of the Normans as the ‘baddies’. When I came to write from their point of view, however, I had to talk myself into looking at things from the other side of the story – which is always an interesting place to be. And so it proved.

I write from a female perspective and am therefore focused on domestic intrigue, human motivation, and political twists and turns, rather than the flesh and blood of the battlefield. I am not suggesting that the women back then (or now) were necessarily less ruthless or vicious than their male counterparts – indeed there is a fabulous woman called Mabel de Bellême whose reputation as a heartless poisoner proves this instantly wrong – but simply that women operated on their estates and at court, rather than with a sword in their hands. What I wanted to research therefore was why the Normans acted in such apparently dark ways. And there are many very sound reasons.

Normandy was a fairly new province in the mid-eleventh century, being only a little over a hundred years old. William was only the seventh duke and was still having to fight to establish and confirm his borders. Plus, William became duke aged only seven when his charismatic father died on pilgrimage. As a child and a bastard-born one at that, his rule was not readily accepted. There were plenty of cousins apparently concerned for the duchy in his control and – more to the point – keen to assert their own claim in his place. As a result there were endless rebellions throughout his early years of rule and stone walls (something Normans became famous for when they introduced castles to England) grew higher.

Inevitably in this warlike climate, the more cultural and domestic sides of life seem to have been neglected. When Mathilda of Flanders arrived to marry William in 1050 I suspect she did not find a place that was terribly congenial for women, especially in contrast to the far more peaceful and sophisticated court she’d grown up in, in Bruges. Mathilda and William’s long reign, however, changed all that.

William successfully put down all rebellions and gradually stability became the norm in Normandy. As a result the ducal pair were able to spearhead a huge programme of church-building which included their own beautiful Abbey aux Hommes and Abbey aux Dames in Caen. From this grand starting point they built Caen up into a hugely prosperous city and they also developed already flourishing Rouen. Bayeux, too, became rich and beautiful under the patronage of William’s extravagant half-brother Bishop Odo and it is safe to say that in the fourteen years between Mathilda marrying William and the invasion of England, Normandy was transformed into a far more stable, prosperous and elegant duchy than it had been before. It was this stability that enabled them, in 1066, to turn their eyes over the narrow sea…

Was William wrong to invade? He did not believe so and the more I researched his story the more I began to see it from his point of view. He was promised the throne by King Edward in Christmas 1051 when the Godwinsons (Harold’s family) were in exile. Most people, King Edward included, may have conveniently forgotten about that promise when the Godwinsons came back into power at court but William never did. It was why, when Harold visited Normandy in 1064, he forced him to swear an oath to uphold him as the next king.

William and Mathilda genuinely believed the English throne was William’s right and he wasn’t alone. When Harold was ‘treacherously’ declared king in January 1066 William sent straight to the Pope to denounce Harold’s reign – and the Pope did so. The Normans marched on England beneath a papal banner offering full benediction for their cause and whilst that may have been a handy political tool, it was also an unequivocal statement of William’s right to invade from the highest Godly authority on earth. It helped him attract soldiers from all over Northern Europe and undoubtedly shored up his own belief in his cause. God, in William’s eyes, wanted William to win – and God made sure that he did. We might sneer at that now but back then it was a very serious matter.

William, I believe, was a hard man but a straightforward and perhaps surprisingly loving one – at least in private. Of the three men fighting to be king of England in 1066 he was the only one who was faithful to his wife. A great man was more or less expected to have mistresses in those times but William never did. This may have been as a result of his Bastardy taint or may just have been his own love for Mathilda but it was remarkable enough for contemporaries to comment on it.

He was also very devoted to his mother, Herleva, and persistently promoted her ‘lowly’ family to high office. He was a man who prized loyalty, who worked hard to surround himself with faithful servants, and who rewarded them well for their devotion. He was not, perhaps, a lovable man, but looking at the 1066 story from his side enabled me to see that he was an earnest one who was driven by duty and a genuine desire to create a better world for his subjects.

And that is what he wanted for England too – but England would not play ball. The Harrowing of the North was a truly terrible act but when you look at it through the eyes of a man who had longed to be king for many years, who was desperate to be a good one, and who had spent his youth fighting off endless rebellions by people who wouldn’t trust him to do his job, it can perhaps been seen less as a cruel act than as a desperate one.

Call me girlie if you wish, but I firmly believe that all William wanted to do was be a good king. It is perhaps as much his tragedy as ours that history didn’t quite work out that way.

For more information about Joanna and her work, you can visit her website (www.joannacourtney.com) or her Amazon author page, and also follow her on Facebook, Twitter or Goodreads

As well as visiting bookshops and libraries as part of my book tour, occasionally I’m also invited to speak about my work in universities and schools, and it’s been my pleasure in the last few weeks to present talks and chair workshops at both Swansea University and Huddersfield New College.

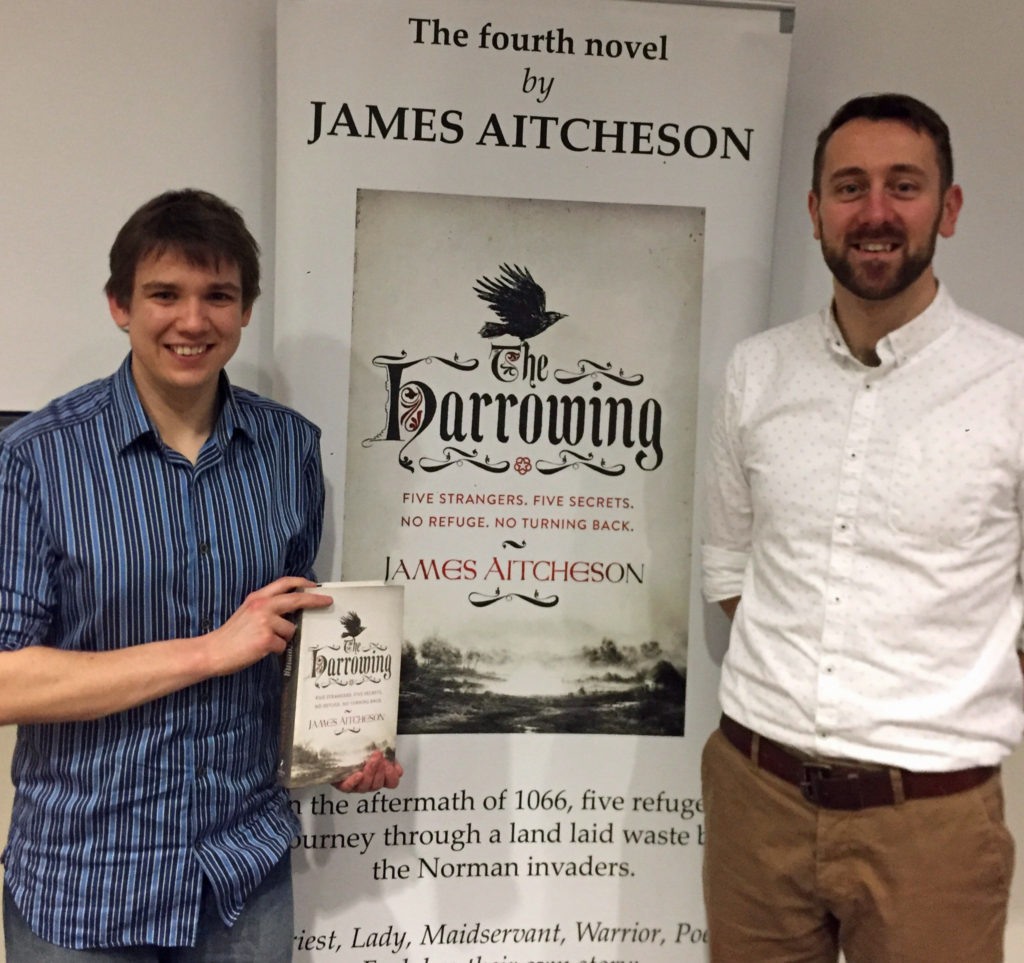

From left to right: myself and Dr Charlie Rozier following my public lecture at Swansea University. Photo credit: Swansea University.

At Swansea I was invited first to co-chair a workshop for medieval history students, looking at primary sources, their value and their limitations. After a short presentation by me, students used extracts relating to the Norman Conquest as inspiration for creative writing – an unusual and in many ways counterintuitive brief to give historians, for whom imaginative interpretation of available evidence doesn’t always come naturally, but an exercise that produced some interesting results.

Later I also gave a public lecture on the process of writing historical fiction, tackling a common question posed by readers, and one that has dominated the debate about the genre for seemingly forever: “Where do you draw the line between fact and fiction?” Drawing upon examples from my own work, I argued that we shouldn’t fixate, as we traditionally have done, on the issue of historical accuracy. Rather, we should celebrate fiction’s potential to understand, interpret and communicate the past in new ways, and I offered some alternative ways of framing the debate regarding the genre.

Both sessions provoked some lively discussion with staff and students, historians and writers alike. I was thrilled to be invited to speak – my thanks to Dr Charlie Rozier (pictured with me, above) for kindly organising the event and making sure the day ran smoothly.

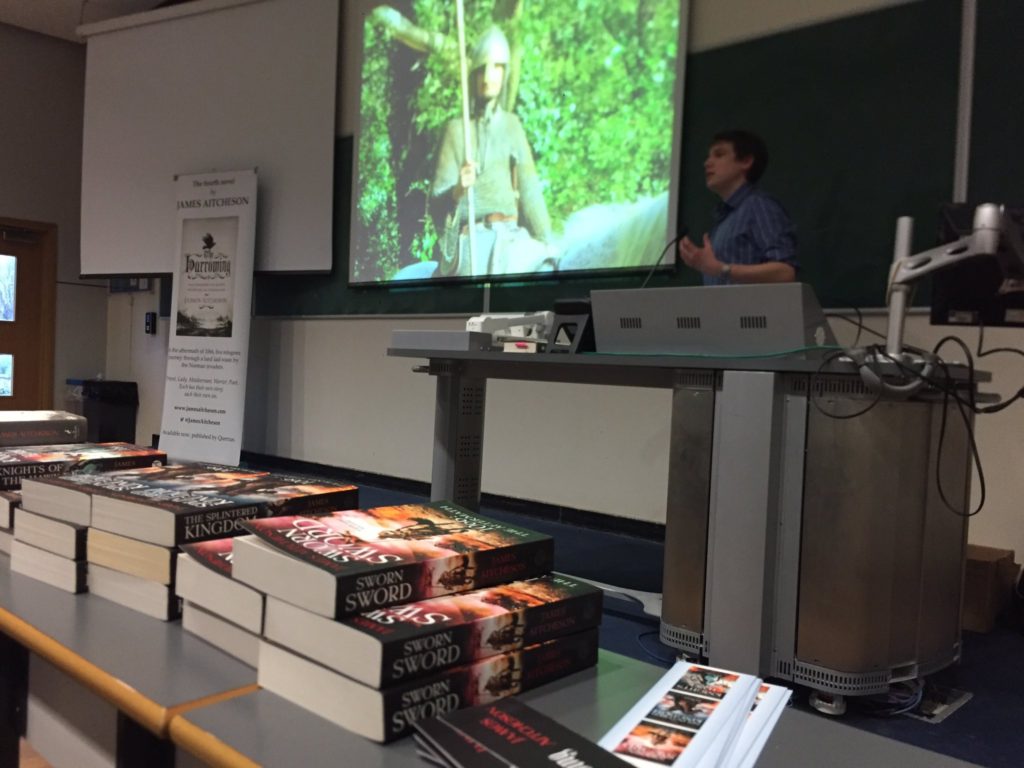

Delivering my public lecture on historical fact and fiction at Swansea University. Photo credit: Charlie Rozier.

The following week I was delighted to return to Huddersfield New College for the third year in a row as their guest author for World Book Day. As well as speaking about the process of researching and writing historical fiction with A-Level medieval and modern history students, I also led a creative workshop based around a series of timed writing challenges designed to free up the imagination and to help writers bypass the internal editor that can sometimes hold them back.

Students were encouraged to write as much or as little as they wanted, without any obligation to share what they’d produced. The challenges varied in difficulty and structuredness, including question-based prompts for generating plots, a picture-based free writing exercise and the ever-popular (and my favourite) “word salad”. I was hugely impressed not just with the energy and enthusiasm the students brought to all of the tasks, but also the range of different responses produced, which often put my own efforts in the shade!

Me (centre, holding The Harrowing) with A-Level students at Huddersfield New College and History course leader Scott Townsend (far right). Photo credit: Huddersfield New College.

Again this year I was given the honour of presenting the certificates at a lunchtime prizegiving ceremony to the winners – chosen by College staff – of the annual short story competition, this year themed upon myths and legends. I also made myself available throughout the afternoon to chat with students about their current writing projects and give advice. It was fantastic to speak to so many keen young writers, and I wish them all the best for their future literary adventures. I’d like to thank Rebecca Hill, the College Librarian, for putting together this year’s event, as well as to Scott Townsend, Sarah Newton and the Principal, Angela Williams, for once more making me feel so welcome.

I’m always happy to visit schools, colleges and universities to speak about my work and to run creative writing sessions. If you’re a teacher, librarian or lecturer and would be interested in hosting a similar event, please do get in touch with me via the Contact page – I’d be glad to discuss some ideas.

With 2016 firmly behind us and January already almost half gone, it’s fair to say that my annual books roundup is long overdue. In this post, I’d like to share with you two of my favourite reads of the year, as well as a handful of other titles to which I’ve awarded honourable mentions.

As with my previous end-of-year reviews, I haven’t focussed exclusively on books that came out in the last twelve months, but have instead compiled a mix of older titles and new releases, across a variety of genres.

If you’ve enjoyed any of the titles below or would like to share your own favourite books of 2016, feel free to join in the discussion on Twitter (@JamesAitcheson) or on Facebook. You can also take a look back at my fiction and non-fiction picks of 2015 and 2014.

The Many Selves of Katherine North

The Many Selves of Katherine North

Emma Geen

Bloomsbury Circus, 368 pp., £14.99

Hardback

I first came across Emma Geen’s work as long ago as 2012, in ARC, a collection of new writing by the 2010-11 cohort of MA in Creative Writing graduates at Bath Spa University. I was instantly captivated by her accomplished prose, and ever since then I’ve been eagerly looking forward to the publication of her debut novel, which is now out in both the UK and the US.

The eponymous heroine, Katherine (Kit for short), is a phenomenaut: one of a select group of teenagers who project their consciousnesses into lab-grown animal bodies – Ressies – in order to carry out ecological research. At 19 years old, Kit is the most experienced and most valued phenomenaut working for Shen Corporation, but after a traumatic incident in one of her jumps as an urban fox, her psychological condition and her readiness for the job is cast into doubt. Withdrawn from research duty and drafted into Shen’s experimental new consumer-oriented programme, she soon begins to call into question the ethics of her paymasters.

A complex and deftly crafted pscyhological thriller that plays upon many of the tropes of speculative fiction, The Many Selves of Katherine North is a sophisticated exploration of – among other things – the nature of consciousness, the concept of self, the exploitation of our natural environment, and the ethics of child labour. As a phenomenaut, Kit has had to sacrifice much of her adolescence in order to pursue her passion, affecting her physical and her social well-being alike. As the novel progresses and she begins to suspect her role as a pawn in the games of others, she becomes ever more uncertain of her identity and place in the world, not to mention her sanity.

Geen’s prose throughout is taut and considered, and yet retains an earthy, sensual quality entirely in keeping with the novel’s themes, while the flitting between past and present lends a feeling of perennial dislocation that helps communicate Kit’s developing paranoia and fragile mental state. Original and inventive, this is a superlative first novel by a gifted writer: without a doubt one of my favourite books of the year, and one that I’m sure I’ll have great pleasure in re-reading very soon.

Hyperion

Hyperion

Dan Simmons

Gollancz, 496 pp., £9.99

Paperback

Shortly after I finished working on the final edits for The Harrowing, I stumbled upon this excellent novel – winner of the 1990 Hugo Award for Best Novel and now part of the SF Masterworks collection, published by Gollancz.

Centuries in the future, humanity has colonised the stars, but civilisation in the form of the Hegemony is under threat, both from the machinations of their AI allies within and from invasion by the barbarian Ousters. With war looming, seven pilgrims are selected to travel to the planet Hyperion and to seek out and appeal to the mysterious, dangerous, demigod-like entity known as the Shrike, in the hope that it might come to the Hegemony’s aid. All of them come from different walks of life, with seemingly little in common.

The book can perhaps be most concisely described as The Canterbury Tales in space, made up as it is of several shorter stories, narrated by each of the pilgrims in turn as they pass the time during their long journey. Having recently finished my own multi-viewpoint novel, also inspired in part by Chaucer, I found myself straightaway absorbed by the concept behind Hyperion and eager to see how Simmons managed to weave the many strands of his novel together.

Each thought-provoking tale offers a different perspective on the culture and history of this richly imagined future society, and each is unique in voice and in the themes it explores. One tale is a horror; another is a romance; a third is a war story and a fourth is a tragedy. To flit between genres so readily and with such panache is far from easy, and is testament to Simmons’ skill and flexibility as a writer.

Not simply an excellent SF novel, Hyperion is also a glorious, genre-spanning feat of literature that fully deserves its many accolades. A TV adaption is reportedly in the works, and there are no fewer than three sequels, although the first volume stands well enough on its own. A magical, compelling read.

Also recommended:

- Nobel Prize-winner Gabriel García Márquez’s colourful One Hundred Years of Solitude, a magical realist tale of the fortunes of the Buendía family over seven generations;

- Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff, a non-fiction novel – one of my all-time favourites – charting the early years of NASA through the stories of the post-war test pilots and the Project Mercury astronauts;

- The Edible Woman, Margaret Atwood’s first published novel, written over 50 years ago and full of her characteristic wit and energy;

- A little-known yet exceptional collection of early short stories by Road Dahl, Over to You, based on his flying experiences during the Second World War.

This week I’m pleased to be interviewing fellow historical novelist Edward Ruadh Butler, the author of the Invader series, which is set in twelfth-century Ireland and begins with Swordland (Accent, 2015).

This week I’m pleased to be interviewing fellow historical novelist Edward Ruadh Butler, the author of the Invader series, which is set in twelfth-century Ireland and begins with Swordland (Accent, 2015).

Ruadh recently ran a Q&A with me on his own website, albeit a Q&A with a difference. Instead of giving me a conventional list of questions to answer, he presented me with a selection of quotations from famous works of literature, including Moby-Dick and The Great Gatsby, which I was invited to reflect upon and respond to however I saw fit.

In this interview, I thought I’d turn the tables, offering up a range of quotes not necessarily from the great novels of the past, but simply from books currently sitting on my shelf. Without further ado, then, I’d like to welcome Ruadh to my blog.

*

“Small beginnings. The principle of the oak tree, and the secret of the successful artist, politician, sportsman. Nice and easy does it.” (From The Mighty Walzer by Howard Jacobson.)

It was never an ambition of mine to write a novel. I love reading. I have done for as long as I can remember and as a kid nearly everything I read had the grand backdrop of history; Herge, Goscinny and Uderzo came first, then Morgan Llywelyn, Mary Stewart, Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson, before Bernard Cornwell came along and I became more than a little obsessive, reading and re-reading his books a number of times. It simply never occurred to me to write since all I really wanted was the next book of Sharpe, Starbuck and Derfel’s escapades!

It was only when I was studying journalism in London in 2007 that the kernel of an idea to write a novel took seed. I was staying with a cousin and came across a whole raft of journals about the Butler family, and, having only the vaguest knowledge of what that meant, I started investigating. They had come to Ireland in the wake of the Norman invasion of 1169, an invasion which had, for better or worse, changed everything in the country, across all strata of society. Surprisingly, it remains a period of history that has been largely unexplored by most people. I had found an untapped treasure trove of stories, of intrigue and adventure, of men and women, in a land so alien to modern eyes. They were stories of remarkable deeds and fascinating characters. I had to write about it. I didn’t know how, but I wasn’t going to let that stop me.

My first attempt was named Spearpoint. Told from the perspective of Dermot MacMurrough, an Irish king exiled from his throne by his enemies in 1166, it simply didn’t work, principally because Dermot proved a little too unsympathetic as a lead character. So I began again, this time from the angle of one of the real-life Norman mercenaries who Dermot had employed to help him reclaim his kingdom.

With a bit of patience – and a number of re-writes – a book called Spearpoint became one called The Outpost with the Welsh-Norman knight Robert FitzStephen as the protagonist for the first time. Further work and fine-tuning (for one hour during my work lunch break as well as a good few weekends and late nights) saw The Outpost become Vanguard.

Swordland • Edward Ruadh Butler • Accent • 478 pp. • £7.99

It was only when I was certain that the book was ready for public view that I sent it to my father’s sailing pal, the late Wallace Clark, a respected (and much missed) travel writer, for his assessment. He loved it but suggested a name change. Thus, Swordland was sent out for the consideration of literary agents in late 2010. It found a home with Accent Press and was published in paperback in April 2016.

“You must understand, therefore, that there are two ways of fighting: by law or by force. The first way is natural to men, and the second to beasts.” (From The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli.)

In the period in which I write it is true that the Normans employed both military and legislative force to overcome the Gael and so conquer much of Ireland. However, it was a much greater power than either ‘law’ or ‘force’ that would win out in the end. This was culture.

The Normans were, without doubt, superior to the Gael militarily but what the invaders met in Ireland was a far older, more vibrant culture to their own, and within two centuries most of the would-be conquerors had absorbed the traditions of those against whom they fought. They had famously become “more Irish than the Irish themselves”. I can think of few circumstances in history where the victorious invader adopted the cultural practices of the conquered to such an extent or so readily.

Of course this campaign was conducted principally through marriage. Wherever they ventured, the Normans married local women, usually well-connected ladies who would give them an advantage politically, but the effect was to inject new ideas into already complex mongrel lineages that the Normans had developed over the previous centuries of conquest.

Most of those who had taken part in the invasion of 1169 were of the second or even third generation living in Wales and as a result as much of their maternal pedigree was Welsh, Breton or Flemish as it was Norman. The central character in Swordland, Robert FitzStephen, was a real-life man and the son of a (presumably) Norman warrior, Stephen of Cardigan, and a Welsh princess, Nest ferch Rhys. It is interesting to imagine the impact that this hybrid background would have on Robert, how it affected his personal and public life, and how it influenced the decisions he made.

The Song of Dermot and the Earl – written in the first half of the 13th century – has Maurice FitzGerald, Robert’s half-brother, upon the walls of besieged Dublin in 1171, just two years after the Normans arrived in Ireland, stating:

“Is it succour from our country that we expect? Nay, such is our lot that what the Irish are to the English, we too, be now considered Irish, are the same. The one island does not hold us in greater desperation than the other. Away, then, with hesitation and cowardice, and let us boldly attack the enemy, while our short stock of provisions yet supplies us with sufficient strength.”

While Maurice is unlikely to have said such a thing, it does give an idea of how his descendants identified themselves during the 1220s. By 1366, these Hibernicised Normans were referred to as “the middle nation” and as a result the English government tried to impose the Statutes of Kilkenny to prevent further degeneration of the settlers. They didn’t succeed. Gaelic culture proved more persuasive than either law or force.

“Tonight the curtain that separates the dead from the living will quiver, fray, and finally vanish. Tonight the dead will cross the bridge of swords.” (From Enemy of God by Bernard Cornwell.)

I’m not a religious person but I do believe that one way for a person to ‘live’ beyond their lifespan is through storytelling. In the future I plan to write about fictional characters, but at the moment it gives me great pleasure to write about the deeds of men and women who really existed (albeit in a fictionalised manner). My characters are people almost forgotten by history, but, by telling their story with as much authenticity and passion as I can muster, I hope that they will be in a sense ‘resurrected’ and the curtain separating their time from ours will indeed vanish – if only in the mind of the reader.

My most recent novel, Lord of the Sea Castle, is currently with my editor and I’m very much looking forward to hearing what he thinks. I really enjoyed writing it. The story picks up right after the end of Swordland and is based around the siege of Baginbun in the summer of 1170. The battle is not terribly well-known today, even in Ireland, but Richard Stanihurst, the celebrated Tudor historian, claimed in 1577 that “by the creek of Baginbun, Ireland was lost and won”. If he is to be believed Baginbun should be remembered as Ireland’s version of the Battle of Hastings. My host, James, will know that this hardly tells the whole story of the conquest of England and it is much the same with its Irish equivalent.

Baginbun Head in County Wexford, where Raymond de Carew made his stand against an army of several thousand Waterford Vikings in summer 1170. You can still identify the remnants of the double embankment he constructed at that time, running between the beaches at the narrowest point.

Without giving too much away, the main character in Lord of the Sea Castle, Raymond de Carew (or Raymond the Fat, as he was more commonly known), leads an advance force of just 120 warriors to Ireland to establish a bridgehead for his lord, Richard de Clare, ahead of his invasion of Ireland. With no hope of aid from home, Raymond is confronted by an alliance of Waterford Vikings and Gaelic tribesmen who outnumber him by at least twenty to one and are bent upon wiping out his small company. The part set in Ireland is lifted almost totally from 12th- and early 13th-century sources. Some of the acts of bravery are so incredible that you might truly believe them to be fictitious! They are deeds worth remembering and I hope I can do them justice.

“Maps and mazes. Of a thing which could not be put back. Not be made right again. In the deep glens where they lived all things were older than man and they hummed of mystery.” (From The Road by Cormac McCarthy.)

One of the great losses to Ireland was Brehon Law. These ‘laws’ came about over several thousands of years before the Norman invasion and are, in their widest terms, a set of ‘fair dinkum’ principles and customs to which all 140 ancient petty-kingdoms in Ireland adhered. They managed to survive and thrive during the Norman colonial period before being stamped out during the second half of the seventeenth century. I find it tantalising to imagine what form it would’ve taken if it had survived and developed through to modern times.

Unlike the rest of medieval Europe which for the most part took on a Romanised form of laws, under the Brehon system the responsibility of law-making and taxation was taken out of the hands of kings. Neither could they create new laws to subjugate their people. Outlandishly for the time, the laws of the land were derived from the bottom of society rather than the top.

Kings could not sit in judgement over the people below them in society and they were subject to the law just like everyone else. Kings were elected from amongst a group of suitable males and they acted as figurehead, particularly in times of war while also being expected to finance judges and poets from an area of land given over to him by the tribe to support him during his time in position. The next holder, considered the most capable at that time, might easily be his brother, son, uncle, or distant cousin.

The law was the realm of the Brehon class. These professional jurists studied the customs of their petty-kingdom and settled disputes. Elsewhere in Europe (and up to the current day) if you committed a crime it was not an offence against your victim, but against the law of the land. In Ireland, the state (represented by the Brehons) was merely the adjudicator between disputing parties. Their rulings were based solely on compensation rather than punishment (even for the worst crimes such as murder) with the ultimate aim being to attain a position of mutual agreement and of resolution. Responsibility for every crime was shared around a kin-group rather than by the offender alone. It was the entire family who put forward monetary sureties and this led to the family unit most commonly trying to rehabilitate unruly members in order to avoid further liability. Only the most wayward in society lost this protection, becoming outlaw and therefore susceptible to killing without risk of legal reprove.

These laws were thousands of years old yet surprisingly modern in many aspects. They were comparatively liberal and compassionate towards women, offering certain protections and independence within marriage and divorce, as well as towards the disabled and children (particularly those of illegitimate birth). Inheritance was equal amongst all the sons rather than having everything inherited by the eldest.

The Normans who came to Ireland were initially subject to English Law but they slowly began to adopt the Brehon customs. Why would they do this rather than look to Dublin or for the king’s judgement? Is it because they found the older laws more fair-minded and impartial than the centralised and distant governments with the monopoly on power?

As a journalist, I spend a great deal of time in court rooms and have seen just how isolated young people can become caught in the criminal justice system, unable to break out of the circle of offending, while going through the list of ineffectual punishments to overly severe sanction that impacts the rest of their life. It seems to me that many caught in this life have devolved personal responsibility to a district judge rather than take it on themselves.

The Brehon Laws put responsibility squarely on the shoulders of those accused of crimes and put them face to face with their accusers. They were asked what it was worth for them to stop aberrant behaviour. It bound their future and finances up with that of their entire family. It caused them to be part of something bigger and more powerful than themselves rather than in opposition to it. The ancient Irish didn’t have to look to the government (or the church) as the adjudicators of good conduct within society. They constructed it themselves and were proud of it.

“I have a story to tell you. It has many beginnings, and perhaps one ending. Perhaps not. Beginnings and endings are contingent things anyway; inventions, devices.” (From The Algebraist by Iain M Banks.)

I’m not a historian. I write historical fiction. Despite writing about people who, for the most part, actually lived, I have no problem changing a few historical details if I think it pushes forward the story. My aim is to make any changes feel authentic to the period and I always try to come clean in the historical note!

One instance was when I had both Dermot MacMurrough and his daughter Aoife able to speak French in Swordland. This was not because I have any evidence that they could, but because it would have been infuriating to have them converse with the Normans through an interpreter at every turn (I also tried everyone speaking in Latin but that didn’t quite work).

Similarly, at the end of the novel I had a major engagement between the High King’s vast army and Robert FitzStephen’s thousand-strong force at Dubh-Tir. This fight never occurred. Instead, the High King is said to have taken one look at the Normans’ newly constructed defences and decided that discretion was the better part of valour, sending forward emissaries to negotiate rather than his spearmen to make battle. That wasn’t an exciting enough conclusion for me and so, having just watched the Bastogne episodes of Band of Brothers (again), I decided to construct a battle in the mountains in the depth of winter for the big finale. I hope it was an exhilarating conclusion to the story, but more so, I hope it came across as truthful to the period in which it was set.

I have taken some liberties with the first half of my next book, Lord of the Sea Castle. In this case it was more out of necessity than choice! Next to nothing is known about the main character, Raymond de Carew, before he landed in Ireland in the summer of 1170 and so I made up a backstory for him, dragging him places he almost certainly never went and allowing him to interact with historical figures that he almost certainly never met. He even gets to attend events to which he undoubtedly would never have been given an invitation! The changes permitted me to look into various aspects of the Welsh Marcher lands, the Viking colony cities in Ireland, and the court of King Henry II which, had I stuck to what is definitively known about Raymond, I might not have had the chance to investigate.

I have taken some liberties with the first half of my next book, Lord of the Sea Castle. In this case it was more out of necessity than choice! Next to nothing is known about the main character, Raymond de Carew, before he landed in Ireland in the summer of 1170 and so I made up a backstory for him, dragging him places he almost certainly never went and allowing him to interact with historical figures that he almost certainly never met. He even gets to attend events to which he undoubtedly would never have been given an invitation! The changes permitted me to look into various aspects of the Welsh Marcher lands, the Viking colony cities in Ireland, and the court of King Henry II which, had I stuck to what is definitively known about Raymond, I might not have had the chance to investigate.

*

Edward Ruadh Butler’s debut novel Swordland is available now, published by Accent Press; the second book in the series, Lord of the Sea Castle is forthcoming. You can find him on Twitter (@ruadhbutler).

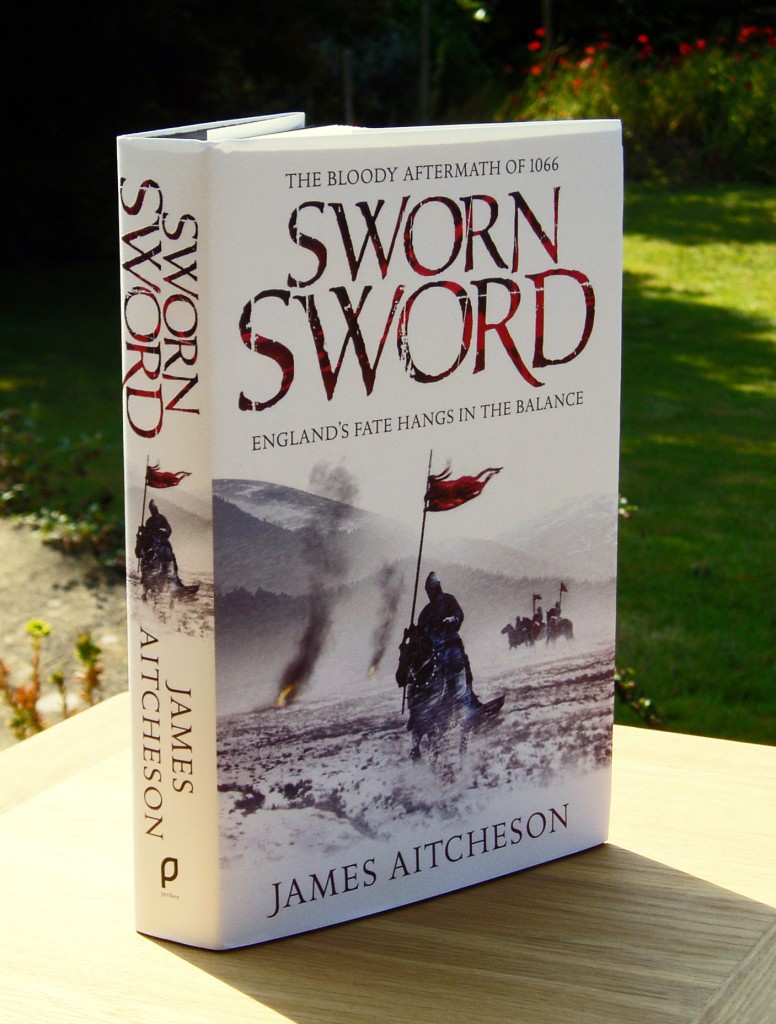

It’s hard to believe, but last month marked the fifth anniversary of the publication of Sworn Sword. My debut novel and the opening instalment in the Conquest trilogy, it arrived in bookshops across the UK for the first time on 4 August 2011.

Where has all that time gone? It seems like only yesterday that I was a wide-eyed young author preparing to release his first work of fiction into the wild, with little experience of literary festivals, book signings or radio interviews and everything else that comes with promoting a book, or indeed much knowledge of the publishing world in general.

My personal copy of Sworn Sword, seen here in pristine condition in August 2011. Nowadays it looks very well-travelled, having accompanied me to many events over the last few years!

Five years on, having just come back from chairing a masterclass on point of view in historical fiction at the Historical Novel Society’s biennial UK conference in Oxford, I realise not only how much I’ve grown as a public speaker, a perfomer and a teacher, passing on my wisdom and hard-won experience – but most especially how far I’ve travelled as a writer.

Four published novels, each very different to the one before it, sometimes in ways that might not necessarily be obvious to the reader, but which to me as the creator are very clear. Around 600,000 words in total, and that’s not including the many revisions, deleted chapters, alternate endings and discarded drafts that never made it into print, nor the pages upon pages of handwritten outlines, character sketches, diagrams or research notes.

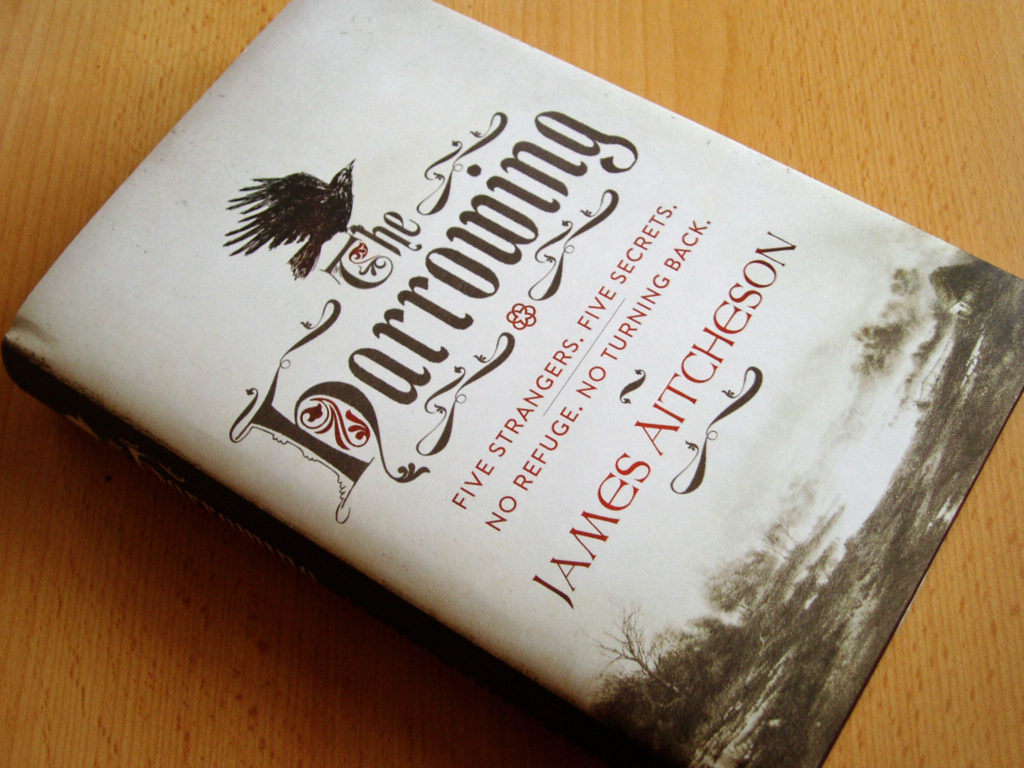

And then there’s The Harrowing. I’m proud of all my books, but I’m proudest of this one, partly because it’s the kind of novel that I’ve always longed to write, but mainly because I feel it represents better than any of my other works the full extent of what I have to offer as a novelist. Of that five year period since 2011, more than half my time has been spent on this one project: researching, drafting, redrafting, re-redrafting, editing, polishing, perfecting.

I’ve adapted and in some aspects entirely reinvented my writing style, learnt to write in different voices, played around with unfamiliar narrative structures and devices, generally challenged myself to do things that I’d never attempted before, and (I believe) emerged from the experience a more complete writer.

My personal copy of The Harrowing, still looking in good condition – for now!

So thank you, readers, for your loyalty and your continued support over the last few years, for following me on Facebook and on Twitter, for reading my blog and listening to my podcasts, for turning out to hear me speak at events up and down the country, and for buying each new book that’s released and thereby following me on this exciting and most rewarding creative journey.

Last year the novelist Joanne Harris presented her writer’s manifesto, making twelve promises to her readers. In a similar way, I’d like to end this blog post by outlining my personal writing philosophy and make some pledges of my own for the next five years and beyond, namely:

- to seek new ways of reaching out to my readers and providing you with insights into my writing process;

- to continue challenging myself both technically and creatively;

- to explore alternative, sometimes unconventional perspectives, as well as different narrative forms;

- to innovate in historical fiction and push the boundaries of what the genre can do;

- never to be afraid of going against the current or of breaking conventions in the name of originality;

- ultimately, to create something the likes of which has never been seen before.

Here’s to the future, and all that it may bring!

Today’s the day that The Harrowing is officially released into the big, wide world! Almost three years have passed since I first began working on it, so to see it finally in bookshops is hugely exciting.

Signed copies of The Harrowing in the London Review Bookshop.

I’d like to take the opportunity to thank everyone at Quercus Publishing who has worked on the novel over the course of its long journey from manuscript to finished product, including my editors Jon Watt and Stefanie Bierwerth, as well as Kathryn Taussig, Olivia Mead and Jeska Lyons, whose hard work has been invaluable.

Signed copies of the book are already available in several bookshops across central London, including but not limited to Foyles, Waterstones Piccadilly, Goldsboro Books and the London Review Bookshop. I’ll be continuing my book tour over the coming weeks with events across the country.

A stack of 100 signed copies of The Harrowing in Goldsboro Books

The Harrowing is also available online through all the usual retailers, and of course is published in digital formats as well to meet your e-reading needs. If you’re based outside the UK and would like to get your hands on a copy, I recommend ordering from the Book Depository, which is based in England but offers free worldwide delivery.

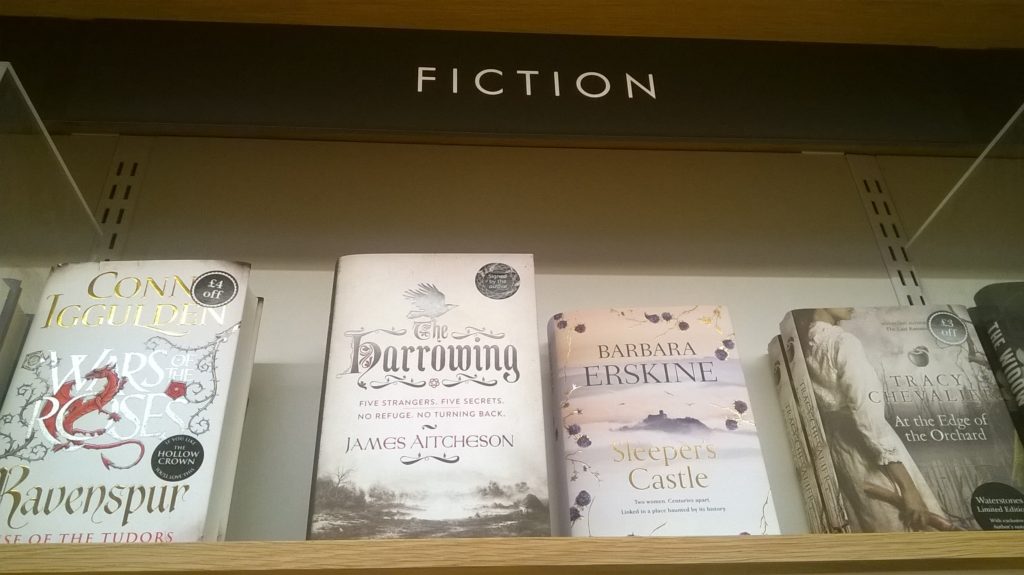

The Harrowing prominently displayed in the hardback fiction section at Waterstones Piccadilly.

I hope you enjoy reading The Harrowing as much as I’ve enjoyed writing it, and I look forward to hearing your comments and feedback over the coming weeks and months! Feel free to get in touch with me at any time, either by emailing me via the Contact page, or through Facebook and Twitter.