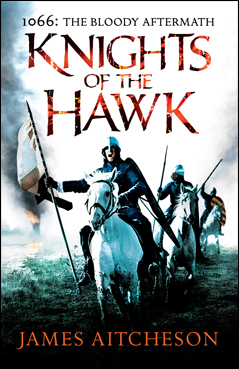

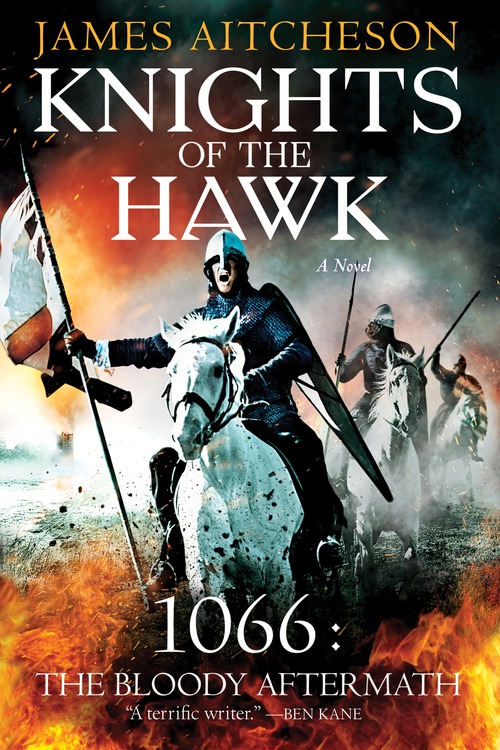

Eight shiny new copies of the US edition of Knights of the Hawk, published by Sourcebooks Landmark.

Look what arrived this week, all the way from Chicago – a boxload of shiny new copies of the hot-off-the-press US hardcover edition of Knights of the Hawk, published by the lovely people at Sourcebooks Landmark!

Many thanks to Stephanie Bowen, Anna Michels, Heather Hall, Kathryn Lynch, Nicole Villeneuve and everyone else on the team at Sourcebooks with whom I’ve had the pleasure of working over the last few years, and who have helped bring the series to thousands of historical fiction aficionados across North America.

And, of course, a massive thank you has to go to you, my readers. I hope you’ve been enjoying reading Tancred’s adventures as much as I’ve been enjoying writing them!

“The sword-path is never a straight road, but rather ever-changing, encompassing many twists and turns. All a man can do is follow it and see where it leads.”

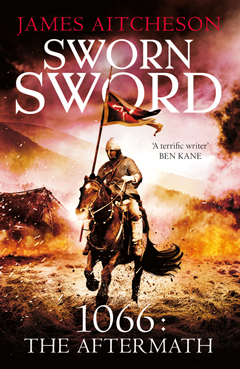

In a little less than a month’s time, Knights of the Hawk, the third instalment in my Conquest Series featuring the knight Tancred, will be released in the United States in hardcover.

Knights of the Hawk • James Aitcheson

Sourcebooks Landmark • 416 pp. • Hardcover • $24.99

Like the previous two volumes in the series, the book will be published by the excellent team at Sourcebooks Landmark, with whom I’ve had the immense pleasure of working over the last three years, and will be available from all good bookstores and online retailers from August 4th.

The cathedral at Ely, built on the site of the Anglo-Saxon monastery which Hereward and his fellow rebels established as their base in the fight against the Normans.

The novel begins during the siege of the Isle of Ely, where the infamous English outlaw Hereward the Wake has gathered a band of rebels to make one final, last-ditch stand against the Normans.

As King William’s attempts to assault the rebels’ island stronghold end in disaster, however, the campaign begins to stall. With morale in camp failing, the king turns to Tancred to deliver the victory that will crush the rebels once and for all and bring England firmly within his grasp. But events are conspiring against Tancred, and soon he stands to lose everything he has fought so hard to gain.

“It is in those final hours, when the prospect of battle has become real and the time for hard spearwork is suddenly close at hand, that a man feels most alone, and when doubt and dread begin to creep into his thoughts. No matter how many foes he has laid low, or how long he has trodden the sword-path, he begins to question whether he is good enough, or whether, in fact, his time has come.”

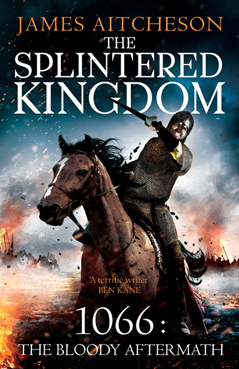

Also, keep a look out for the U.S. paperback edition of The Splintered Kingdom, which will be published by Sourcebooks Landmark in November. I’ll be posting more information about that in the coming months.

What makes a great first sentence? What do people look for in the opening of a novel? How do authors grab readers’ attentions and entice them to read on?

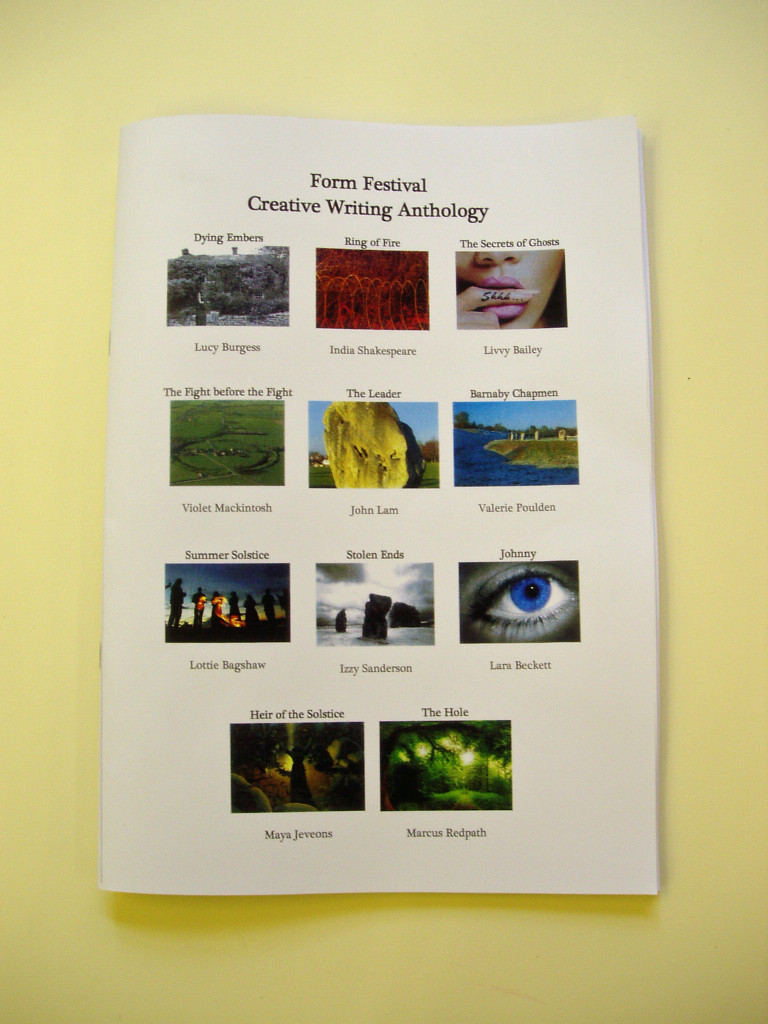

These were some of the questions I posed last week when I visited Marlborough College to lead a two-day creative writing workshop for a group of Year 9s as part of their summer term’s Form Festival. The ancient monuments at nearby Avebury provided the inspiration, the students provided the creativity, and the end result was the very smart-looking anthology pictured here!

After spending a few hours exploring the ancient stones and the museums at Avebury, and trying to imagine the kinds of people who might have lived there through the ages, we returned to the College in the afternoon armed with character concepts and the seeds for possible plots.

With guidance, suggestions and feedback from me, the students then started to use the ideas they’d come up with to write a short story or the first chapter of a novel. At the end of the second day, all the pieces, complete with blurbs and front covers, were collected into the volume shown above, which was printed for the rest of the school to read and enjoy.

One of the two Portal Stones at Avebury, Wiltshire.

Although the main focus of the workshop was historical fiction, the students were encouraged to let their imaginations run wild and to write in whatever genre they liked, so long as their stories were connected in some way to Avebury.

What emerged from the workshop was an amazing outpouring of creativity. The tales produced took place in all periods of history, from the Neolithic to the Viking Age to the modern day; they featured supernatural forces, ancient rituals, long-forgotten battles, mysterious ruins, and a diverse range of characters including druids, archaeologists and a prehistoric proto-suffragette rebelling against the traditions of her tribe.

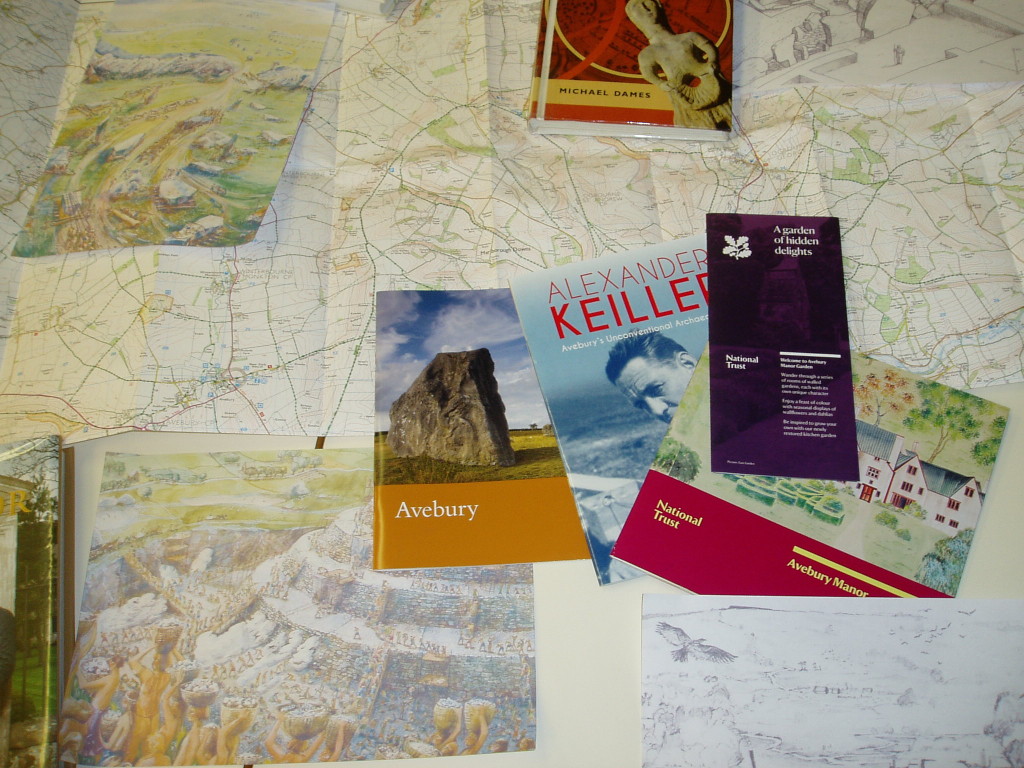

Some of the research materials used to generate ideas, including maps, artists’ renderings and (of course) books!

Thanks to everyone at Marlborough College for making me feel so welcome over the two days I was there. It was a pleasure to work with such an enthusiastic group of writers, and I wish them the best of luck for the future.

*

Earlier this year, I was invited to give a talk about the Norman Conquest and also to run a creative writing workshop at Huddersfield New College to celebrate this year’s World Book Day.

The creative writing session was based around a series of short, fun challenges designed to help free up the imagination, spark ideas and (above all) overcome the fear of the blank page – an affliction that strikes all authors from time to time.

Here I am with the creative writing group at Huddersfield New College

on World Book Day 2015. Photo credit: Huddersfield New College.

I was blown away with the range and quality of writing produced in response to the various challenges I set. The workshop was enormous fun for me as well as for the students, as I think you can tell from our grins in the photo above, taken at the end of the workshop.

As at Marlborough, the welcome I received from both staff and students in Huddersfield was absolutely terrific. With any luck my being there will have inspired a few to go on to study History or to develop their writing further! I certainly felt very privileged to be in the presence of so many talented young authors, and I hope to be able to return in the not too distant future.

*

If you’d like to get in touch about organising a creative writing workshop at your school, college, library or festival, you can do so via the Contact page.

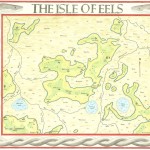

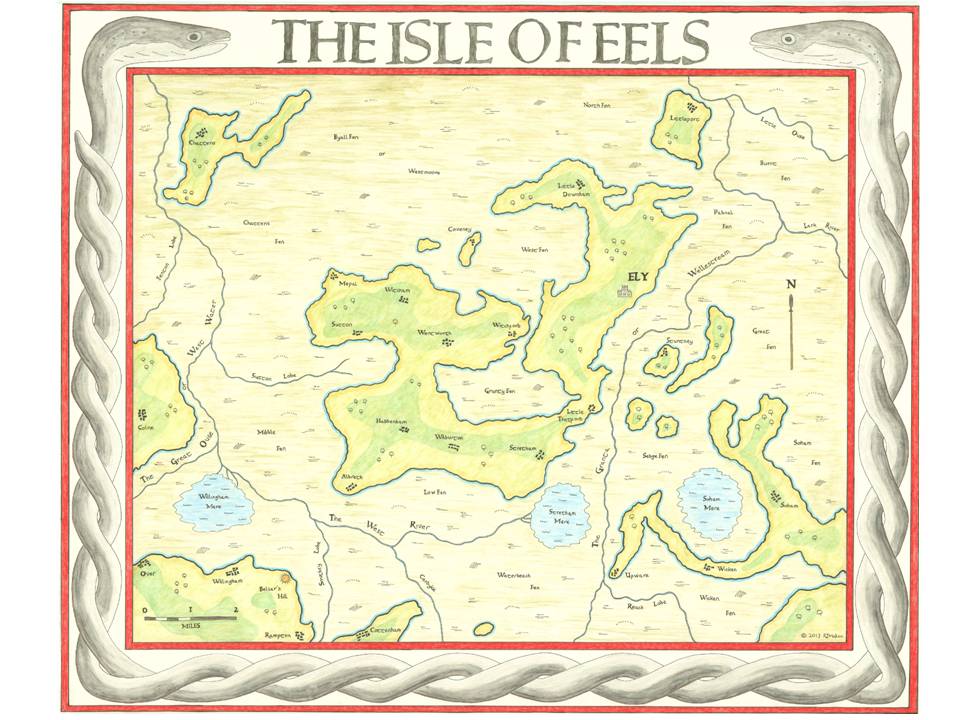

This week I’m pleased to be interviewing author and artist Rus Madon, the creator of the Isle of Eels map (below). The map reconstructs the historical geography of the Fens around Ely as they would have appeared at the time of the Norman Conquest: specifically in 1071, when Hereward the Wake and other rebels used the Isle as a base from which to conduct their guerilla war against the invaders.

Rus recently sent me a copy of his meticulously researched map, a remarkable piece of work and a wonderful resource for anyone fascinated, as I am, by the Fens and the role that they played in the years that followed 1066.

His work was also featured recently on the British Library’s blog. You can find him on Twitter at @RusMadon.

*

What was the initial inspiration for researching and creating the map, and how long did it take you to complete?

I am writing a Young Adult story about a girl who lives in modern-day Ely. She travels back in time to the year 1071 when Ely was defended against the Normans by Hereward the Wake. The more I wrote about 11th-century Ely, the more I wondered what it actually looked like. I knew that Ely had been an island, and I was having difficulty tracking where my characters were in relation to the original fens. So to help answer the question, I set about drawing a map of medieval Ely.

Including doing all the research, it took 200 hours to complete the map over an 8 month period in 2013. The original map is 1m x 1.2m and I had to make a workspace in the loft for all the materials, as it was too big to work on in the house!

Was this the first time you’d tackled a project like this?

The proper answer is yes. I do not have an artistic bone in my body, and made several attempts before ending up with the version you see. The eels in the border were particularly challenging (or should I say slippery!).

However, when I was a teenager in the mid 1970s, I spent an entire summer holiday recreating the map of Middle Earth from The Lord of the Rings. By coincidence, that is also 1m x 1.2m, and was drawn on a big piece of butcher’s paper! It hangs on the wall next to my map of Ely.

However, when I was a teenager in the mid 1970s, I spent an entire summer holiday recreating the map of Middle Earth from The Lord of the Rings. By coincidence, that is also 1m x 1.2m, and was drawn on a big piece of butcher’s paper! It hangs on the wall next to my map of Ely.

The Romans were the first to try to drain the Fens. How much evidence of their activities can still be seen in the landscape today?

Well, the Romans were first and foremost engineers, and they managed to tame many environments across Europe. But the might of Rome met her match with the fens! The landscape of the fens was too wild and impenetrable for the Romans to have any real success in their attempts to drain them.

However, the Romans did build several causeways to make travel easier, the most famous of which was the Fen Causeway, or Fen Road. This linked Denver, near Downham Market, to Peterborough, but it essentially was a road at the northern edge of the fens, which at that time would have been a coast road, as the modern coastline is many miles further north than it was in Roman times. Another causeway linked Cambridge with Ely, some of which is now part of the A10 trunk road and can be seen near Denny Abbey.

They also excavated the Cardyke (visible on my map). This canal system linked the Granta (now the Cam) to the West River and allowed movement of goods and people through the river system of the fens.

Since the marshes were drained in the seventeenth century it has obviously changed a great deal. How difficult was it to rediscover the medieval Fens?

It was harder than I expected. At first I simply tried searching online for a copy of how the fens would have looked, and that would have been sufficient for what I needed. But there were no definitive sources I could find. I also became aware that researchers had published material, but the information was not easily accessible.

What became apparent was that my task had two elements to it. The first was to try and understand how the land would have looked. This was relatively straightforward, as whilst the level of the water table has dropped since the fens were drained, the geology that created the “islands” has not changed at all (in other words, there has been no undue erosion of the landmass).

By far the most difficult part of the research was to try and understand how the waterways would have looked, and how they linked together. The river systems that people living in Ely today will recognise is very different to that of a thousand years ago. Today, the Ouse runs west to east and joins the Cam before heading North past Ely. The Cam (Granta) has not changed much since those times, but it came to light that the West River flowed east to west and joined the Great Ouse to head north to the left of Ely! This was a very different system to that seen today. The courses of the Ouse changed principally because of the two huge artificial drainage ditches that were constructed to the northwest of Ely (the Bedford Rivers), commissioned by the 4th Earl of Bedford in 1630 to help in the process of draining the fens.

By far the most difficult part of the research was to try and understand how the waterways would have looked, and how they linked together. The river systems that people living in Ely today will recognise is very different to that of a thousand years ago. Today, the Ouse runs west to east and joins the Cam before heading North past Ely. The Cam (Granta) has not changed much since those times, but it came to light that the West River flowed east to west and joined the Great Ouse to head north to the left of Ely! This was a very different system to that seen today. The courses of the Ouse changed principally because of the two huge artificial drainage ditches that were constructed to the northwest of Ely (the Bedford Rivers), commissioned by the 4th Earl of Bedford in 1630 to help in the process of draining the fens.

What sources did you use to delve into this lost landscape?

I used the resources of the British Library to look for the oldest maps of the area prior to the Dutch draining the fens in the 17th century. All maps of the area are thought to derive from a survey of the area carried out by William Hayward at the beginning of the 17th century. This map was destroyed in a fire, but it is believed that Sir Robert Cotton, a keen collector of fenland maps, had a copy made (The Cotton Map). It is an extraordinary document. Looking at the hand drawn map, you can see the lost Isle of Eels emerging from the fens, as if I was looking back in time.

I supplemented this information with a review of existing Ordnance Survey maps, using the 5-metre contour line to sketch out land that would have been above the ancient water table. In the British Library I came across a pivotal paper published by Major Gordon Fowler in 1934. This paper outlined the possible ancient watercourses of the area. Along with several other authors and notably the excellent Henry Darby, I pieced together how the rivers would have flowed around the island in Saxon times.

The final step was to add the main settlements that would have existed in 1071. For this I used a mixture of references from Domesday Book and the Liber Eliensis, the so-called Book of Ely, written in the 12th century by monks at Ely Abbey.

[NOTE: A full list of references can be found at the end of Rus’s article on the British Library’s blog.]

How much fieldwork did you have to do and what did that involve? How useful was it to be on the ground?

During the summer of 2013 I drove the back roads and lanes that criss-cross the island, making adjustments to my notes, extending the sweep of a hill, noting natural hollows in the ground, and removing the causeways and embankments that had been added much later. Without doubt, being on the ground helped add context to the map.

But for me, on a personal level, it was more than a matter of accuracy. Seeing the landscape allowed me to connect with the map, it helped guide my hand when I was back in my draughty cold loft, transcribing the information; it made the map live for me.

Were there any particularly unusual or surprising nuggets of information that you turned up in the course of your research?

Were there any particularly unusual or surprising nuggets of information that you turned up in the course of your research?

My discovery that the modern day Ouse had a completely different route and was not joined to the Cam surprised me. But to some extent, that was a matter of historical record, I simply needed the time to find the information.

However, some of the old books I read in the British Library gave vivid accounts of the fens in medieval times. The people were a breed apart; tough, independent, wary of outsiders. They wore eel skins to ward off illness and bad spirits. They would fight fiercely to defend their homes. The fens themselves were thriving with life, with bitterns, swans and eels. I read of Flag Iris, a beautiful carpet of flowers with a fragrant scent; but if a man stood on it, he would be sucked deep into the waters below. There was one account of a pod of whales that swam into the Granta from the sea. They became stuck in a small tributary and died. For many decades their skeletons were a reminder of the dangers of the fens.

So what did I do with all these nuggets? I am a writer, so I weaved them into my story, to bring it alive, to make it real.

How do you plan to use the map now that it’s finished?

Now that the map is complete (a copy of which I donated to the British Library), I can travel back in time to 1071 and see the Isle of Eels through the eyes of my characters. It has allowed me to be more credible when describing their adventures.

It is also my intention for the map to be part of the book, so that the readers can also see what Ely would have looked like in the eleventh century. Maybe one day, if my book is a success, the map will become as famous as the one of Middle Earth…

As 2014 draws to a close, the time has come for me to reveal my favourite books of the year. A few of these are relatively new releases, published within the last twelve months, although some are older.

I’ve divided the list into three sections – fiction, non-fiction and graphical novels – so I hope that there’ll be something for everyone. As you might expect, there’s a strong historical slant: the Middle Ages feature particularly strongly, but my choices also cover Roman Britain, Tudor England and the nineteenth century.

If you’ve enjoyed any of the titles below or would like to share your own favourite books of 2014, feel free to join in the discussion on Twitter (@James Aitcheson) or on Facebook.

Fiction

Alias Grace

Alias Grace

Margaret Atwood

Virago, 560 pp., £8.99

Paperback

Margaret Atwood never fails to impress me with the brilliance of her prose and the scope of her ambition. In a year in which I’ve read no fewer than six of her novels, Alias Grace is the one that has most stood out, and which has left the greatest impression on me.

Based on real events that took place in 1840s Canada, the novel centres upon former housemaid Grace Marks, recently convicted of the murder of her employer and his mistress, and sentenced to life imprisonment. But serious doubts remain regarding her guilt, as the earnest young proto-psychiatist Dr Simon Jordan discovers when he comes to investigate her case.

Told partly through Grace’s eyes and partly from Dr Jordan’s perspective, the novel is an absolute tour de force. Atwood’s prose sparkles throughout, her research into the period is impeccable and her characters are nuanced and fully realised. Alias Grace is one of the most absorbing and complete historical novels I’ve read, and one that almost certainly I will be returning to soon.

Beowulf

Beowulf

Seamus Heaney (trans.)

Faber & Faber, 256 pp., £12.99

Paperback

As a medieval scholar, it shames me to admit that until this year I’d never read Beowulf, perhaps the most famous text written in the Old English language. The exact date of its composition is unknown, although it is unlikely to be less than 1100 years old and perhaps much older, but the tale of the eponymous hero’s struggles against the monster Grendel and, later, against the dragon remains as compelling now as undoubtedly it was to its Anglo-Saxon audience.

The translation, by the late Seamus Heaney, captures the hero’s vitality and the drama of his deeds, and is all the more absorbing and thrilling when it is read aloud. This bilingual edition uniquely features the original Old English text alongside the translation for easy reference.

Also recommended:

- Gentlemen of the Road, a swashbuckling tale of derring-do in the medieval Khazar Empire, by celebrated author Michael Chabon;

- Atwood’s new collection of short stories, Stone Mattress, which was published this summer;

- CJ Sansom’s latest Shardlake novel, Lamentation, set during the final months of Henry VIII’s reign.

Graphic novels

The Complete Maus

The Complete Maus

Art Spiegelman

Penguin, 296 pp., £16.99

Paperback

For the first time my end-of-year list includes a graphic novel, although graphic memoir or biography might be a more appropriate term. Art Spiegelman’s harrowing telling of his father Vladek’s experiences as a survivor of the Holocaust won the Pulitzer Prize when it was published, and deservedly so.

By choosing to depict the subjects of his narrative not as humans but as anthropomorphic animals, Spiegelman takes a bold step, and one that has come in for more than its fair share of criticism. Far from trivialising the events he describes as a cat-and-mouse chase, however, the effect is to allow him to depict subject matter that otherwise might be too horrific for the reader to bear.

Maus is a masterpiece of the genre, a prime example of the power of the graphic novel if ever there was any doubt. Spiegelman’s companion book, MetaMaus, is also well worth reading, for the insights it offers into his early career and how the project came about, his research, the decisions he made in the course of writing the book, and how it affected his relationships not just with his father but with his own children as well.

Non-fiction

Worlds of Arthur

Worlds of Arthur

Guy Halsall

OUP, 384 pp., £10.99

Paperback

The fifth century, which witnessed some of the most momentous events in British history – the end of Roman rule and the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons – is a period shrouded in mystery. In this hugely important study, Guy Halsall demolishes the pseudo-historical case for the existence of King Arthur and examines the historical and archaeological evidence for what took place in that dark age.

Halsall assumes no prior knowledge, although some of the source analysis may seem impenetrable to the general reader, and so some familiarity with the discussions surrounding the period will undoubtedly help. While not all readers will necessarily agree that the evidence supports his specific conclusions, nevertheless Halsall succeeds in opening up the debate on post-Roman Britain and suggesting some new avenues of enquiry. Cogently argued and well illustrated throughout, this is an excellent piece of scholarship – history writing at its best.

The King in the North

The King in the North

Max Adams

Head of Zeus, 464 pp., £9.99

Paperback

The early Anglo-Saxon period is one largely unknown nowadays except to specialists. In this accessible and compelling history, Max Adams rescues from obscurity one of the most powerful rulers of that age: King Oswald of Northumbria (r. 634-42), who according to the historian Bede “brought under his dominion all the nations and provinces of Britain”, and whose reign witnessed the establishment of Christianity and the foundation of the famous monastery at Lindisfarne.

Less a biography of a single man than it is a study of a dynasty, The King in the North depicts a ruthless and volatile world in which Britons fought Anglo-Saxons, pagans fought Christians, and fortunes of entire kingdoms could be overtuned at a single sword’s blow. For a more in-depth discussion, take a look at the fuller review I penned earlier in the year.

Magna Carta: a Very Short Introduction

Magna Carta: a Very Short Introduction

Nicholas Vicent

OUP, 152 pp., £7.99

Paperback

2015 will mark the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta, the great charter between King John and his barons that sought to restrict and regulate royal authority. The document casts a long shadow: even today, it’s often held up as one of the cornerstones of modern democracy, not just in Britain but in the United States as well.

Nicholas Vincent examines the history and context of Magna Carta, including how it was reinterpreted and reframed in the generations following 1215, and asks whether the mythic status that it has acquired over the centuries is justified. Concise and yet comprehensive, it includes a translation of the full text of the original issue. An excellent introduction to the subject.

Also recommended:

- Jared Diamond’s latest book The World Until Yesterday, in which he asks whether as wealthy Westerners we can learn any lessons from traditional, pre-industrial, stateless societies;

- The Middle Ages: a Very Short Introduction, Miri Rubin’s new addition to the long-running series from Oxford University Press, which offers a broad overview of medieval Europe and its society and culture.

- Under Another Sky, part travelogue and part work of history, in which classicist and journalist Charlotte Higgins explores the legacy of the Romans in Britain.

Many thanks to everyone who entered my recent prize draws on Twitter to celebrate the arrival of the festive season. Each week since the beginning of December I’ve been giving away two signed paperback copies of one of the books from my Conquest Series.

The Conquest Series (so far…)

Each week’s winners have been selected using a random number generator from all the entries received. And so without further ado, here they are:

Week 1

Sworn Sword

@JamesRees83

@AJWatersAuthor

Week 2

The Splintered Kingdom

@eblueaxe

@amaz_ed

Week 3

Knights of the Hawk

@RebellionJason

@shaun_chalky

Congratulations to the winners – I’ll be contacting you directly on Twitter. If you didn’t win, better luck next time! For full details of the competitions, click here.