Knights of the Hawk • James Aitcheson

Arrow • Paperback • £6.99

Knights, the third novel in the Conquest Series, which is due to be published in paperback in the UK on Thursday 22nd May, sees Tancred journeying further afield than ever before, setting out across the length and breadth of Britain and making common cause with some unlikely allies as he strives for honour, vengeance and love.

Set in the autumn of 1071, Knights of the Hawk begins during the siege of the Isle of Ely, where the infamous English outlaw Hereward the Wake has gathered a band of rebels to make one final, last-ditch stand against the Normans. As King William’s attempts to assault the rebels’ island stronghold end in disaster, however, the campaign begins to stall. With morale in camp failing, the king turns to Tancred to deliver the victory that will crush the rebels once and for all and bring England firmly within his grasp. But events are conspiring against Tancred, and soon he stands to lose everything he has fought so hard to gain.

Look out for it appearing in a bookshop or a supermarket near you. As always, e-book editions are available on all platforms for the more technologically inclined. If you can’t wait until publication day to get a taste of what’s in store, you can read an extract from the beginning of the book.

And if you’re interested in finding out more about the setting and how the landscape might have looked at the time of the Norman Conquest, there’s an entry on Ely and the Fens in “Tancred’s England”, my historical guide to the kingdom c.1066. Don’t worry, there are no spoilers! As a special web-only bonus, there’s also a map of how the area would have looked in the Middle Ages before the marshes were drained, which unfortunately there wasn’t space to include in the book.

All three books (so far) in the Conquest Series:

UK paperback editions.

Readers in the US unfortunately have a little longer to wait before Knights is available, but in the meantime there’s The Splintered Kingdom to look forward to. Set in the borderlands between England and Wales, it’ll be published this August, and I’ll be revealing more about it in the coming months. Watch this space!

On this week’s edition of In Our Time, the long-running BBC Radio 4 series, the topic under discussion was Domesday Book. One of the most significant documents in English history, it is unparalleled in form and scope, and one of the greatest legacies of the Norman Conquest.

Commissioned by William the Conqueror in 1085, it is, in essence, a kingdom-wide record of who held what estates and other assets in England and how much they were all worth. The level of detail sought by the men carrying out the inquest was remarkable, even if not all of it necessarily made it into the final, edited version. As one of our key sources for the period, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, comments in its entry describing the Domesday Survey:

“…there was not one single hide, not one yard of land, not even (it is shameful to tell – but it seemed no shame for him to do it) one ox, not one cow, not one pig was left out, that was not set down in his [King William’s] record.”

Joining Melvyn Bragg to discuss Domesday Book, the circumstances of its creation, the processes of the survey that supplied the information, its contents and its lasting impact, were three eminent scholars of the Norman Conquest: Elisabeth van Houts, David Bates and Stephen Baxter. It’s a fascinating debate; even after 900 years there remain several unanswered questions as to how it was put together and the exact reason for its being commissioned.

If you missed it, you can catch up online or else download the discussion as a podcast to listen to later from the BBC website. The In Our Time archive includes many excellent programmes related to Anglo-Saxon England and the Norman Conquest, and indeed history in general. In time I plan to compile a list of the best ones and post the links here on the website for anyone who’s interested in finding out more.

For the moment, however, here are two of my favourite programmes from the archives: firstly, Alfred and the Battle of Edington, about the West Saxon king’s struggles against the Viking invaders; and secondly, if you’re looking for further insight into life in England post-1066, The Norman Yoke, exploring and questioning the idea that the Conquest was necessarily a Bad Thing that resulted in many years of harsh oppression for the Anglo-Saxons.

If you’re interested in looking deeper into Domesday Book, meanwhile, or in exploring the history of your own home town or village, you need go no further than the Open Domesday project. Combining map data with records from the survey, it’s a visual, searchable database of who held what property in England, both on the eve of the Conquest in 1066 and at the time of the survey two decades later. It’s free to access, and easy to use.

And of course I can’t talk about Domesday Book and go without mentioning my own grand historical survey of the kingdom of England c.1066, Tancred’s England. With just three location entries so far, it’s not quite on the scale of that eleventh-century masterwork, which records 13,418 places and contains over 2 million words, but I’ll be adding to it bit by bit over the coming months. Any comments, including suggestions for other places that I could feature in Tancred’s England, are welcome – just let me know via the Contact page.

Today I’m launching a brand new section here on the website! Eagle-eyed visitors might already have noticed the new link on the menu bar above, nestled between Bio and Blog. Entitled Tancred’s England, the idea is to offer an insight into the history behind some of the key places featured in the Conquest Series, and to share some of the research that goes into the writing of the novels.

Baile Hill, on the western bank of the River Ouse, is all that survives of York’s second castle, constructed in spring 1069.

So far you’ll see that I’ve posted information about three locations, and there will be more to follow in due course. To begin with I’ve chosen to feature the two great Anglo-Saxon cities of York and London, as well as Ely and the Fens – where the English outlaw Hereward and his allies made their stand against King William in 1071.

The valley of the River Teme to the north of Knighton, not far from Tancred’s fictional manor of Earnford. Taken from Offa’s Dyke Path, looking north-west.

I’ll be expanding the Tancred’s England section and adding fresh content to each of these pages in the coming months, with entries on Durham, Bristol and the Welsh March all in the works. So keep checking back from time to time to see what’s new, and if you have any suggestions for things that I could add or which you’d like to know more about, please get in touch with me via the Contact page.

Tell your friends! Today, the brand new paperback edition of Sworn Sword will be hitting bookshelves across the United States. Featuring an updated, more vibrant cover design (similar to the UK paperback cover; see below right), it also contains a short excerpt from the sequel, The Splintered Kingdom, which is due to be published this August and of which I’ll be posting more details here in the next few months.

Sworn Sword • James Aitcheson • Sourcebooks Landmark • 400 pp.

Trade paperback • $14.99

I’m pleased to say, as well, that Sworn Sword has been picking up excellent reviews since its hardback publication last summer, including one in Publishers Weekly and another recently in the Philadelphia Inquirer. Thanks to all those of you who have kindly taken the time to email me through the Contact page or sent messages on Twitter and Facebook to say how much you’ve enjoyed the book and are looking forward to Tancred’s further adventures. He and his brothers-in-arms will ride again in the not-too-distant future!

If you already own the hardcover edition of Sworn Sword and can’t wait until August to find out where Tancred’s travels will be taking him in The Splintered Kingdom, you can find the synopsis as well as the first chapter, which is available to download for free, here.

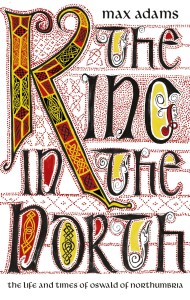

A prince-in-exile makes his triumphant return from obscurity, slaying the tyrant who was ravaging his homeland and reclaiming the throne that, half a lifetime earlier, was stolen from him, before establishing himself as one of the pre-eminent kings of his age and ushering in a golden age for his people. The story of King Oswald of Northumbria (reigned 634-42) is a remarkable one – indeed the stuff of legend – and yet nowadays his achievements have largely been forgotten by most except Anglo-Saxon specialists.

The King in the North

Max Adams • 448 pp. • Head of Zeus

Hardback • £25.00

In keeping with the book’s subtitle, “the life and times of Oswald of Northumbria”, Adams does not examine his subject’s career in isolation, but also explores the array of societies and cultures – religious and secular – that inhabited seventh-century Britain, and so places his reign in its historical context. While Oswald, his achievements and his afterlife as the focus of a saintly cult form the backbone of the book, a significant amount of attention is given also to the career of his predecessor Edwin (616-32) as well as to the long reign of his successor, his brother Oswiu (642-70). Indeed The King in the North is less a biography of a single man than it is a study of a dynasty, and of the leading role played by Northumbria in the politics, religion and culture of seventh-century Britain. This was a land divided: a land of seemingly perpetual conflict between rival families, Anglo-Saxons and Britons, new and old customs, pagans and Christians, and even between different branches of the Church: the Irish, the British and the Roman traditions.

Oswald’s reign as king was relatively short – only eight years – and yet his impact in that time was decisive in forging the Northumbrian kingdom. After ousting a Welsh army from his ancestral homelands in order to claim his crown, he proceeded first to unite the ancient provinces of Bernicia and Deira under one rule and, later, to win a great victory over a coalition of forces drawn from the southern Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, which in the following century led the historian Bede to assert that he had “brought under his dominion all the nations and provinces of Britain.”

Exactly how much can and should be read into these words isn’t clear. It would perhaps have been useful to have seen a deeper interrogation of Bede’s statement, which Adams accepts at more or less face value. There’s no doubt that both Oswald and Oswiu were among the most powerful rulers of their age, and widely respected throughout these isles. What’s more questionable is the extent to which they can be justifiably said to have been overlords over all the kingdoms of Britain, south as well as north of the Humber. What might this overlordship have entailed? How might it have been achieved and exercised in practice? What was the exact extent of their authority, and was it was uniform throughout the territories that lay beyond their kingdom’s borders? Given that their power base was centred upon Bamburgh, it is hard to imagine how they could have exercised much influence over Wessex or Kent, for example.

Lindisfarne Castle on Holy Island. The castle was built in 1550, re-using stone from the Norman priory. (Photo credit: Matthew Hunt. Reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic licence.)

Around these events Adams expertly weaves his account. If the title of The King in the North is intended as a nod towards George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series, then the comparison between the world of Oswald and that of Eddard Stark is an apt one. The political landscape of seventh-century Britain was a ruthless and volatile one, in which rival dynasties pursued vicious bloodfeuds and in which fortunes of entire kingdoms could be overtuned at a single sword’s blow. Elaborately constructed networks of alliances and tribute rarely outlived the rulers at their head. Power rested in the hands of the most military successful: those who were able to attract the largest warbands, and who were able to prove their throne-worthiness through victory in battle.

The great triumph of Adams’ study is in bringing all this to life. Impeccably researched, compellingly written and accessible to the general reader as well as to the specialist scholar, The King in the North vividly reconstructs the world that Oswald not only inhabited but also helped to shape.

The ruins of St Andrews Cathedral. At 119 metres (391 feet) in length, it’s the largest church ever to have been built in Scotland.

As well as giving a paper of my own on representing the Middle Ages in fiction, I also had the chance to meet and share ideas with historians and people from a wide range of other academic disciplines whose work involves the medieval in one way or another.

I was also privileged to be able to attend the lecture that closed the conference, which was delivered by Nobel Prize-winning poet Seamus Heaney in what was probably one of his final public appearances before he died just a couple of months later.

Five of the keynote lectures, including Heaney’s, were recorded on video and have now been posted on the conference website for anyone interested in getting a taste of what the conference was all about. The five lectures are:

Saints’ cults and celebrity: the medieval legacy

James Robinson (National Museums Scotland)

Adapting medieval romance

Felicitas Hoppe (author and translator)

The worlding of medievalism: past and present in the early anthropocene

Bruce Holsinger (University of Virginia)

European ethnicity: does Europe have too much past?

Patrick Geary (Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton)

“Feinyit Fablis and Ane Cairfull Dyt”?: a Reading with Commentary

Seamus Heaney (Nobel Prize-winning poet)

The week following the conference, the British Academy in London held a special event with Patrick Geary and broadcaster, actor and writer Terry Jones, chaired by Dr Chris Jones from the University of St Andrews, in which they reprised their presentations and discussed the continuing relevance of the Middle Ages. The video of this event is also now online on the British Academy website.

All of the lectures are well worth watching if you have the chance. Between them they give a fairly good idea of the variety of subjects that were discussed over the four days, exploring how ideas and misconceptions of the Middle Ages have informed, and are reflected, in disciplines as wide-ranging as literature, politics and even climatology, which was the focus of Bruce Holsinger’s particularly excellent talk – just one of my many highlights of the conference.

In case you missed them the first time around, catch up with Part One and Part Two of my report from “The Middle Ages in the Modern World”.