This summer, after writing professionally for eight years, I finally penned my very first short story.

To some readers of this blog this may come as a surprise. Creative writing guides often advise those getting started to begin with short fiction: it is regarded by many as part and parcel of the traditional apprenticeship that writers must undergo. The short story, according to the theory, is the training ground where we’re supposed to hone our craft, to find our voice, to tighten our prose, to learn the skills that will allow us to tackle our bigger projects.

The beach at Manorbier, Pembrokeshire, pictured here on a grey and chilly April day in 2017, offered the inspiration for one of my short stories this summer.

There’s a certain logic to this school of thought. A novel is a mountain: to scale it takes considerable planning and preparation followed by a long and arduous climb to the summit, punctuated by unforeseen obstacles that aren’t always visible from base camp. And the metaphorical descent can be just as tricky, as you return over ground already covered: editing, reassessing and rewriting, often repeatedly. The prospect is daunting, and there are any number of reasons to give up along the way. The gratification that comes with completion can seem forever out of reach; it’s easy to misinterpret the constant struggle as a sign of failure.

The short story, on the other hand, offers a quicker route to that sense of gratification. For the novice, the knowledge of having completed something is invaluable: it is validation of one’s own ability. Success breeds confidence, and confidence breeds success. It’s a virtuous circle, or at least that’s the principle. It enables experimentation without risk.

But writing short fiction has its own unique challenges. Few of us read it, and even those of us who do tend not to consume it in the same quantity that we consume novels. If we don’t read it, how can we expect to be able to write it? When in 2006 I started out on my writer’s journey I certainly hadn’t read enough short stories to understand their form and structure. I did attempt to write a few, but without a clear idea of what I was trying to achieve, and so I soon abandoned them. What I wanted was to write a novel, and so with the single-mindedness of youth I set out from the beginning to do exactly that.

It’s only now – after an MA in Creative Writing, four published novels and now the first year of a PhD – that I feel I understand my craft well enough that I’m able to graduate from the novel to the shorter form. The short story is more technical, more succinct; it requires greater precision of language and phrasing. Every word matters. What is not said can be just as important as that which is made explicit. Working out how best to exploit the negative space around the words can reap immense rewards, but takes time.

A short story doesn’t obey the same conventions as its longer counterpart. It can be a puzzle for the reader to crack; it can pose questions without the pressure of having to offer resolution. In its very brevity it offers complexity. The process of writing one is certainly shorter, but not necessarily any easier than writing a novel. It requires skills that my younger self twelve years ago simply did not possess.

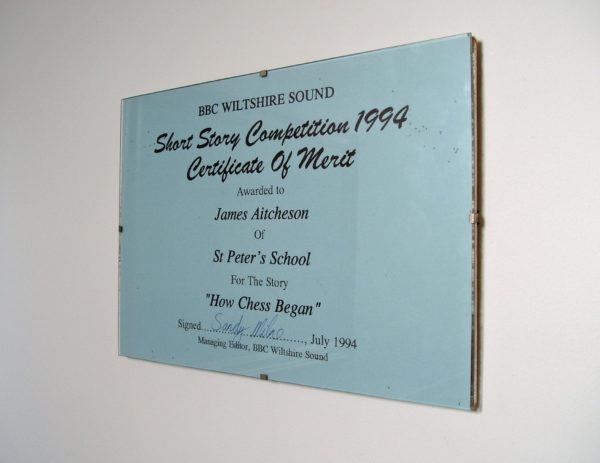

Disclaimer: in saying that I haven’t written a short story before, I’m obviously not counting the one I wrote when I was eight, which won me this lovely certificate from BBC Wiltshire Sound.

For me, writing short stories this summer has offered me a chance to experiment with voice, form and prose technique, to break away from my usual habits and comfort zones, and to test ideas for my bigger project – the novel that forms the heart of my PhD thesis. It has been liberating, allowing me to expand my horizons beyond historical fiction and try out other genres for the first time in years. (Not that I’ve ever seen myself purely as a historical novelist: that’s simply where my career has happened to take me so far.)

These past few months have been some of the most creative I’ve experienced, and the stories I’ve produced are, I believe, some of my most challenging and imaginative work. As I turn now back towards thinking about the novel, I feel reinvigorated but also increasingly aware of the possibilities of the longer form – and increasingly confident in my own ability to achieve them. More than ever I feel I’m on the cusp of something very exciting: I’m redefining myself as an author.

Get ready for James Aitcheson 2.0.