In a way, it’s reassuring to know that, amidst the pandemic-induced tumult that has engulfed the world, The Archers – that famous Radio 4 institution – remains a coronavirus-free zone. Life in the fictional community of Ambridge continues miraculously as it ever has done, sans the lockdown and self-isolation measures witnessed by the rest of us.

For now, at least. Enough episodes have been recorded that the long-running radio soap will keep going in its current format until the end of this month, with (presumably) no references to the dreaded c-word being made during that time.

From May, however, all that will change. The BBC’s recent announcement reveals that coronavirus will indeed begin to feature, “in a way that the programme’s many loyal listeners might expect”, and that the format will be different, too, with individual cast members recording their parts from home studios.

But with fiction in this case taking so long to catch up with reality, there are some important questions worth raising about the relationship between the two. To what extent do we expect fiction to reflect the real world that we see around us? How important is it that fiction – whether in the form of radio drama, film and television, or novels – keeps up with rapidly developing current events?

We are, of course, primed to accept a certain level of artificiality in our fictions. We know that there is no Ambridge, no Felpersham, no Borsetshire. We know that these places – and their associated characters – exist in a setting which is not actually rural Britain but a simulacrum, an amalgam of rural Britain, and not even that but rather than insulated pocket within that imagined world.

We take these things as given. We readily accept that The Archers represents an alternate or parallel reality, a pretence, an illusion. And yet, as series editor Jeremy Howe says, one of the programme’s aims to offer “a picture of the way we live now in rural England”. That is to say, if it doesn’t bear at least some relation to the texture of real life – if it does not feel authentic – then it will not satisfy its listeners.

The BBC’s press release reminds us that topical events such as England’s progress during the World Cup have often been added to scripts, not only keeping the programme up-to-date but also sustaining the sense of authenticity required in order to render this fictional world believable.

But where does one draw the line? How much of the real world should be permitted to intrude upon the lives of these characters? Which real-world events are important enough that they must be included, and which can be disregarded? More widely, we might well ask: what do we want to see from the fiction that we consume – both during the current crisis and otherwise? Is its role to represent and respond to reality, or to offer a diversion from it?

“For nearly 70 years Ambridge has been a haven for our audience, and so it continues to be,” Howe says. “Whilst Coronavirus might be coming to Borsetshire, listeners can still expect The Archers to be an escape [emphasis added].”

On how he intends to reconcile these two apparently divergent aims, however – to provide both “a picture of the way we live now” and “an escape” – he remains tight-lipped. It will be interesting to see what course the programme steers over the coming months.

The reason these questions have occupied my attention this week isn’t because I’m a devoted listener of The Archers (sorry, Ambridge fans) but because many of the same issues arise in my own work and research, albeit in relation to the past rather than the present.

What is it that gives a historical novel authenticity? How closely must a novel set in the past adhere to real events, cultures, social customs etc., in order for it to qualify as “historical” fiction? Would it be better if we considered all works set in the past to be essentially a form of counterfactual (“what if?”) narrative – imagined, possible versions of events that bear some resemblance to reality, without necessarily making any claim to represent it?

These are the sorts of questions I’ve been asking over the past two-and-a-half years during the course of my PhD at the University of Nottingham, and which I’ve been trying to answer while working on my latest novel and the thesis that accompanies it.

Whether we’re writing about the past or the present or the future, there will always be a natural tension between fiction and reality. That said, imagining how things could be different either now or in the future, or how they might have happened (or happened differently) in the past, is what fiction has always excelled at. Moreover, the power of these alternative realities to contextualise our present situation – and allow us to see it in a different light – should not be underestimated.

Would it be a problem if The Archers were to continue blithely on its own timeline – if it remained pandemic-free indefinitely? I wonder.

Why is there no historical note in The Harrowing? A number of readers have asked me this over the past two-and-a-half years since the novel was first published. It’s a question that, I’ve come to realise, goes to the heart of what I believe historical fiction is all about. In this post I’ll explore my decision not to include a note (no, it wasn’t down to laziness) and how this fits into my wider philosophy as regards writing fiction set in the past.

In all three of my Conquest novels, first published in the UK between 2011 and 2013, the final chapter or epilogue is followed by an appendix in which I contextualise the story by exploring the real-life events, cultures and individuals who inspired it. In this very short essay – never more than around 2,000 to 2,500 words, or roughly 5 to 6 pages in the printed book – I would offer an insight into some of my preparatory research and the primary sources I’ve relied upon, deconstruct the novel’s relationship to the historical record, and highlight particular occasions where the truth is uncertain, where I’ve used artistic licence, or where I’ve deliberately introduced a fictional element.

The historical note, or author’s note, or afterword – whatever one wishes to call it – is these days a standard element of the historical novel, especially at the commercial end of the market. It’s my general impression that it’s slightly less common at literary end, although by no means is it unheard of. Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood and Burial Rites by Hannah Kent are two prominent examples of novels containing such a note that spring to mind, being as they are conveniently placed on the shelf above my desk as I write this piece. Needless to say, historical notes vary considerably in length: in the case of Burial Rites, it’s a mere three pages; by contrast, C.J. Sansom concludes his latest Shardlake novel, Tombland, with a 60-page essay.

The key reason why I elected not to write a historical note for The Harrowing was my desire to let the story speak for itself. I won’t give any spoilers here, but suffice it to say that the novel finishes on a touching moment, balanced between optimism and tragedy, and with a complex swirl of emotions in play. It felt appropriate to give the reader space to digest the resolution and decide how they feel about the events described, rather than allow the authorial voice to intrude and puncture the atmosphere. Closing the book with Tova’s words rather than my own felt more respectful towards her, the other characters and the journey they have completed – and on which the reader has followed them.

The end, in this case, really is the end. There is no story beyond the story; the novel’s meaning is not complicated or revised by the addition of an appendix that seeks to provide a broader picture, or that brings the reader back to ‘reality’. Demonstrating the narrative’s historical underpinnings would, in this case, have severely undermined what I was trying to achieve.

After all, my rationale for using fiction rather than non-fiction to explore the Harrying of the North – the devastating campaign that saw the Normans lay waste to vast tracts of northern England during the winter of 1069–70 – was that the bare facts and figures seemed insufficient to convey the true horror of this episode. No first-hand accounts of this event have been handed down to us by its victims; their stories have been lost forever. The only way to give voices back to those people, to make sense of their experience, to see them as individual human beings and to rescue them from being relegated to mere statistics, was through fiction.

For that reason, to fall back at the end of the book upon statistics, dates and sources relating to the Harrying of the North as justification or context for the narrative would have seemed to me like an admission of defeat. It would have diminished the creative process, the act of imagination and the attempt to forge an emotional connection with the past, by implying that the story was not robust enough to stand on its own merits.

Here we come to the crux of the matter. In 2017, in an interview at the Oxford Literary Festival, Hilary Mantel criticised her fellow historical novelists who, in her words, ‘try to burnish their credentials by affixing a bibliography’. She said: ‘You have the authority of the imagination, you have legitimacy. Take it. Do not spend your life in apologetic cringing because you think you are some inferior form of historian. The trades are different but complementary.’

The historical note, it is true, offers novelists a chance to set the record straight. In it we can demonstrate the breadth and depth of our reading. In this way, we are arguing for the right to be taken seriously – a natural impulse. But by doing so we are actually asking to be judged by the standards of a different discipline, and so inadvertently diminishing our own status as writers. It is a defensive act rather than a positive statement of our own distinct and legitimate authority.

Novelists, it should go without saying, are not historians. Historical fiction, no matter how well researched, is not history. Its value as a literary genre lies elsewhere. Where? Well, that’s a weighty subject in its own right, and one that I’ll save for another day and another blog post. Suffice it to say for now that historical fiction is the product of a different set of skills, and it is those skills – the craft and technique that we have each developed as writers – that we should be celebrating and drawing particular attention to.

Historians and other scholars are required to show their workings if they are to build a convincing argument. For artists it is different: what matters above all is the final piece. I would much rather these days that my work speaks directly to the reader. That’s why, for me, the historical note has become redundant: not because I have nothing to say, but because to say it would risk dispelling the magic. Yes, it’s always fun to see how the trick is done, but we revel more in the mystery. Less, as so often, is more.

For both narrative and philosophical reasons, then, there is no historical note in The Harrowing. Will there be one in my current work-in-progress? Probably not. That’s not to say I can’t envisage a future novel that might be enhanced by such a note. For now, though, I’m content to keep separate my twin identities – the novelist and the medievalist – and to let them work freely and independently in their own respective ways.

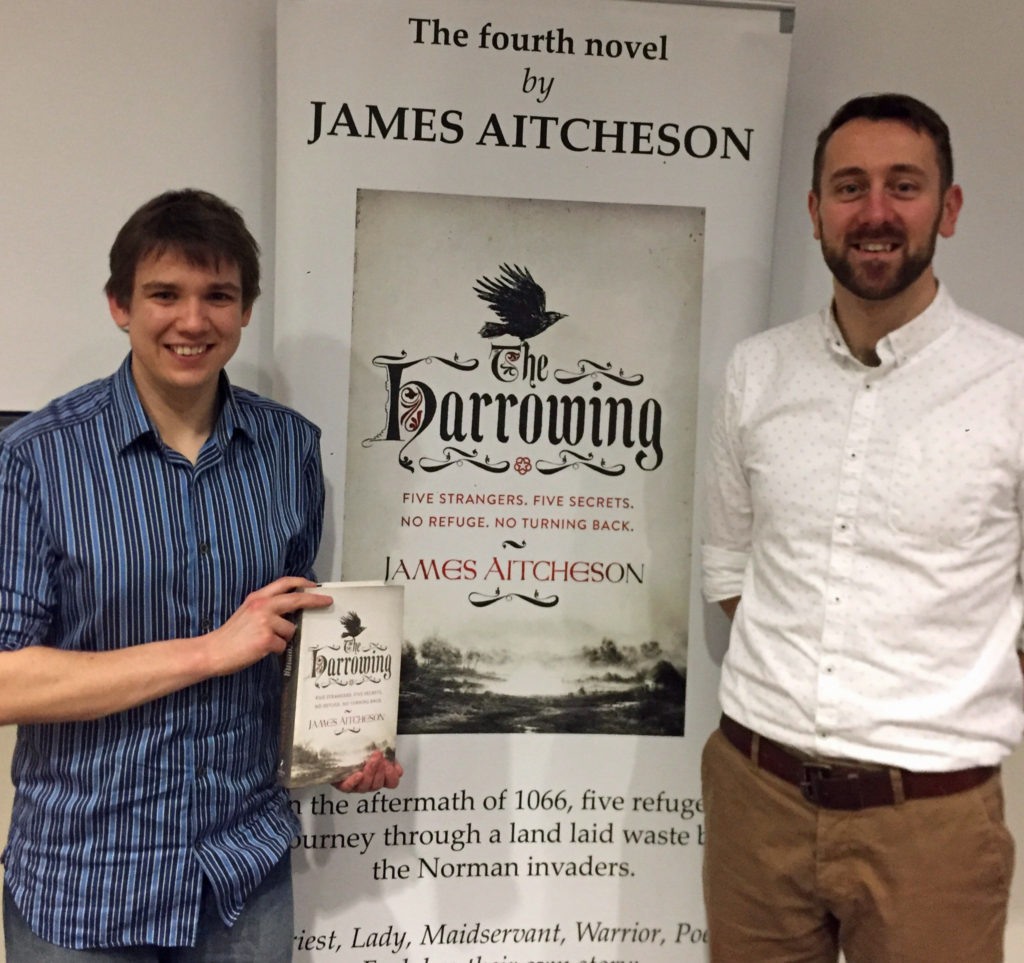

As well as visiting bookshops and libraries as part of my book tour, occasionally I’m also invited to speak about my work in universities and schools, and it’s been my pleasure in the last few weeks to present talks and chair workshops at both Swansea University and Huddersfield New College.

From left to right: myself and Dr Charlie Rozier following my public lecture at Swansea University. Photo credit: Swansea University.

At Swansea I was invited first to co-chair a workshop for medieval history students, looking at primary sources, their value and their limitations. After a short presentation by me, students used extracts relating to the Norman Conquest as inspiration for creative writing – an unusual and in many ways counterintuitive brief to give historians, for whom imaginative interpretation of available evidence doesn’t always come naturally, but an exercise that produced some interesting results.

Later I also gave a public lecture on the process of writing historical fiction, tackling a common question posed by readers, and one that has dominated the debate about the genre for seemingly forever: “Where do you draw the line between fact and fiction?” Drawing upon examples from my own work, I argued that we shouldn’t fixate, as we traditionally have done, on the issue of historical accuracy. Rather, we should celebrate fiction’s potential to understand, interpret and communicate the past in new ways, and I offered some alternative ways of framing the debate regarding the genre.

Both sessions provoked some lively discussion with staff and students, historians and writers alike. I was thrilled to be invited to speak – my thanks to Dr Charlie Rozier (pictured with me, above) for kindly organising the event and making sure the day ran smoothly.

Delivering my public lecture on historical fact and fiction at Swansea University. Photo credit: Charlie Rozier.

The following week I was delighted to return to Huddersfield New College for the third year in a row as their guest author for World Book Day. As well as speaking about the process of researching and writing historical fiction with A-Level medieval and modern history students, I also led a creative workshop based around a series of timed writing challenges designed to free up the imagination and to help writers bypass the internal editor that can sometimes hold them back.

Students were encouraged to write as much or as little as they wanted, without any obligation to share what they’d produced. The challenges varied in difficulty and structuredness, including question-based prompts for generating plots, a picture-based free writing exercise and the ever-popular (and my favourite) “word salad”. I was hugely impressed not just with the energy and enthusiasm the students brought to all of the tasks, but also the range of different responses produced, which often put my own efforts in the shade!

Me (centre, holding The Harrowing) with A-Level students at Huddersfield New College and History course leader Scott Townsend (far right). Photo credit: Huddersfield New College.

Again this year I was given the honour of presenting the certificates at a lunchtime prizegiving ceremony to the winners – chosen by College staff – of the annual short story competition, this year themed upon myths and legends. I also made myself available throughout the afternoon to chat with students about their current writing projects and give advice. It was fantastic to speak to so many keen young writers, and I wish them all the best for their future literary adventures. I’d like to thank Rebecca Hill, the College Librarian, for putting together this year’s event, as well as to Scott Townsend, Sarah Newton and the Principal, Angela Williams, for once more making me feel so welcome.

I’m always happy to visit schools, colleges and universities to speak about my work and to run creative writing sessions. If you’re a teacher, librarian or lecturer and would be interested in hosting a similar event, please do get in touch with me via the Contact page – I’d be glad to discuss some ideas.

“The sword-path is never a straight road, but rather ever-changing, encompassing many twists and turns. All a man can do is follow it and see where it leads.”

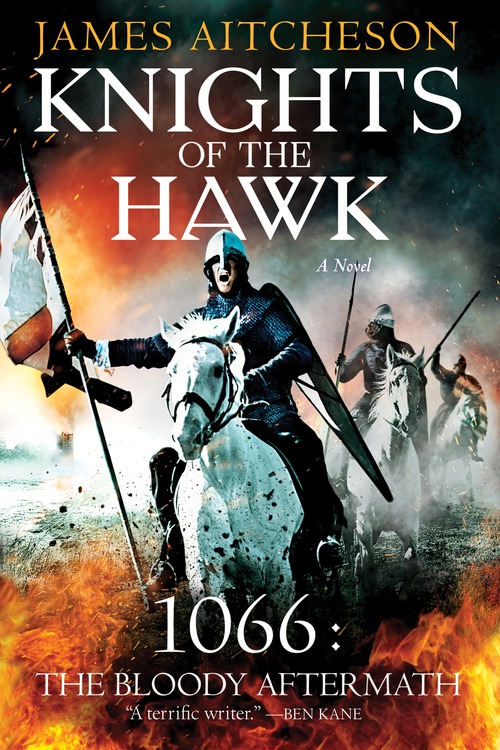

In a little less than a month’s time, Knights of the Hawk, the third instalment in my Conquest Series featuring the knight Tancred, will be released in the United States in hardcover.

Knights of the Hawk • James Aitcheson

Sourcebooks Landmark • 416 pp. • Hardcover • $24.99

Like the previous two volumes in the series, the book will be published by the excellent team at Sourcebooks Landmark, with whom I’ve had the immense pleasure of working over the last three years, and will be available from all good bookstores and online retailers from August 4th.

The cathedral at Ely, built on the site of the Anglo-Saxon monastery which Hereward and his fellow rebels established as their base in the fight against the Normans.

The novel begins during the siege of the Isle of Ely, where the infamous English outlaw Hereward the Wake has gathered a band of rebels to make one final, last-ditch stand against the Normans.

As King William’s attempts to assault the rebels’ island stronghold end in disaster, however, the campaign begins to stall. With morale in camp failing, the king turns to Tancred to deliver the victory that will crush the rebels once and for all and bring England firmly within his grasp. But events are conspiring against Tancred, and soon he stands to lose everything he has fought so hard to gain.

“It is in those final hours, when the prospect of battle has become real and the time for hard spearwork is suddenly close at hand, that a man feels most alone, and when doubt and dread begin to creep into his thoughts. No matter how many foes he has laid low, or how long he has trodden the sword-path, he begins to question whether he is good enough, or whether, in fact, his time has come.”

Also, keep a look out for the U.S. paperback edition of The Splintered Kingdom, which will be published by Sourcebooks Landmark in November. I’ll be posting more information about that in the coming months.

What makes a great first sentence? What do people look for in the opening of a novel? How do authors grab readers’ attentions and entice them to read on?

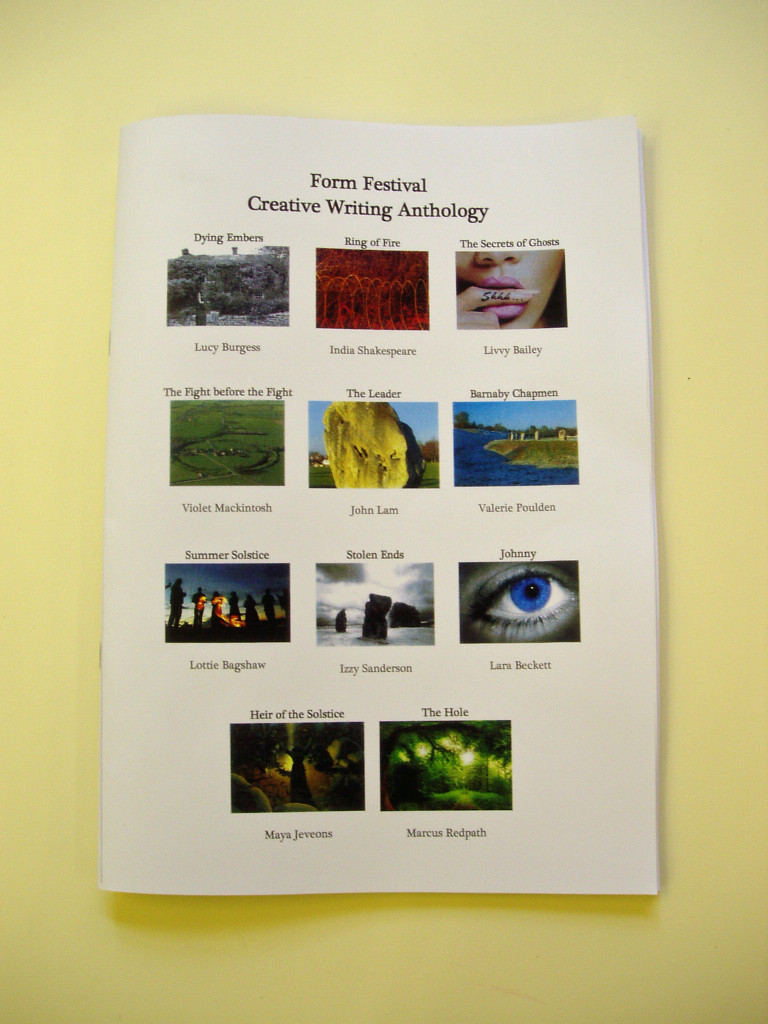

These were some of the questions I posed last week when I visited Marlborough College to lead a two-day creative writing workshop for a group of Year 9s as part of their summer term’s Form Festival. The ancient monuments at nearby Avebury provided the inspiration, the students provided the creativity, and the end result was the very smart-looking anthology pictured here!

After spending a few hours exploring the ancient stones and the museums at Avebury, and trying to imagine the kinds of people who might have lived there through the ages, we returned to the College in the afternoon armed with character concepts and the seeds for possible plots.

With guidance, suggestions and feedback from me, the students then started to use the ideas they’d come up with to write a short story or the first chapter of a novel. At the end of the second day, all the pieces, complete with blurbs and front covers, were collected into the volume shown above, which was printed for the rest of the school to read and enjoy.

One of the two Portal Stones at Avebury, Wiltshire.

Although the main focus of the workshop was historical fiction, the students were encouraged to let their imaginations run wild and to write in whatever genre they liked, so long as their stories were connected in some way to Avebury.

What emerged from the workshop was an amazing outpouring of creativity. The tales produced took place in all periods of history, from the Neolithic to the Viking Age to the modern day; they featured supernatural forces, ancient rituals, long-forgotten battles, mysterious ruins, and a diverse range of characters including druids, archaeologists and a prehistoric proto-suffragette rebelling against the traditions of her tribe.

Some of the research materials used to generate ideas, including maps, artists’ renderings and (of course) books!

Thanks to everyone at Marlborough College for making me feel so welcome over the two days I was there. It was a pleasure to work with such an enthusiastic group of writers, and I wish them the best of luck for the future.

*

Earlier this year, I was invited to give a talk about the Norman Conquest and also to run a creative writing workshop at Huddersfield New College to celebrate this year’s World Book Day.

The creative writing session was based around a series of short, fun challenges designed to help free up the imagination, spark ideas and (above all) overcome the fear of the blank page – an affliction that strikes all authors from time to time.

Here I am with the creative writing group at Huddersfield New College

on World Book Day 2015. Photo credit: Huddersfield New College.

I was blown away with the range and quality of writing produced in response to the various challenges I set. The workshop was enormous fun for me as well as for the students, as I think you can tell from our grins in the photo above, taken at the end of the workshop.

As at Marlborough, the welcome I received from both staff and students in Huddersfield was absolutely terrific. With any luck my being there will have inspired a few to go on to study History or to develop their writing further! I certainly felt very privileged to be in the presence of so many talented young authors, and I hope to be able to return in the not too distant future.

*

If you’d like to get in touch about organising a creative writing workshop at your school, college, library or festival, you can do so via the Contact page.

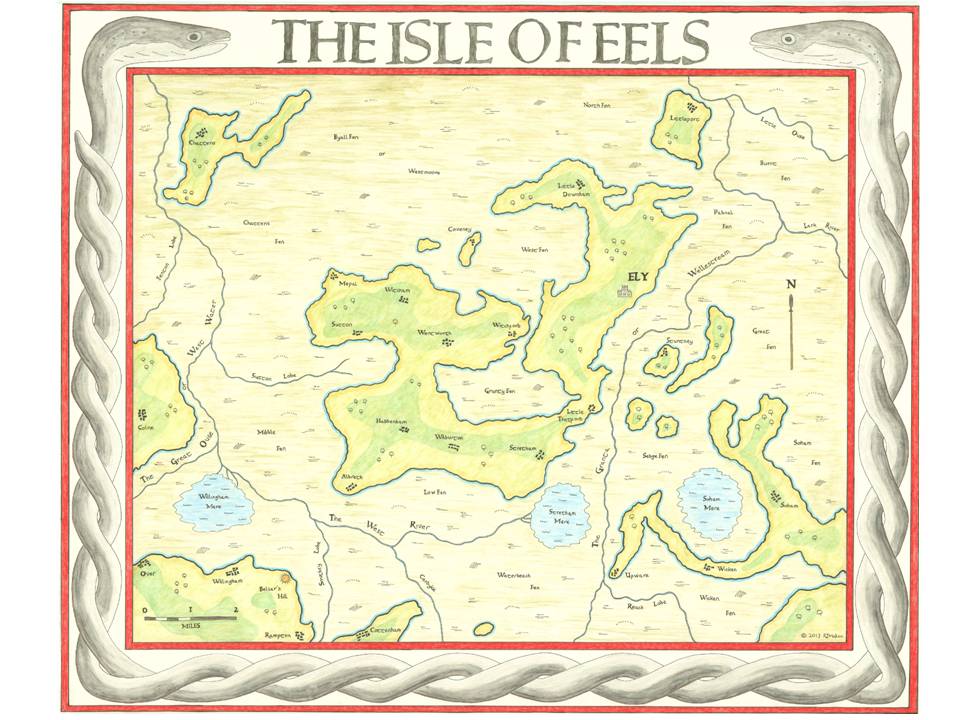

This week I’m pleased to be interviewing author and artist Rus Madon, the creator of the Isle of Eels map (below). The map reconstructs the historical geography of the Fens around Ely as they would have appeared at the time of the Norman Conquest: specifically in 1071, when Hereward the Wake and other rebels used the Isle as a base from which to conduct their guerilla war against the invaders.

Rus recently sent me a copy of his meticulously researched map, a remarkable piece of work and a wonderful resource for anyone fascinated, as I am, by the Fens and the role that they played in the years that followed 1066.

His work was also featured recently on the British Library’s blog. You can find him on Twitter at @RusMadon.

*

What was the initial inspiration for researching and creating the map, and how long did it take you to complete?

I am writing a Young Adult story about a girl who lives in modern-day Ely. She travels back in time to the year 1071 when Ely was defended against the Normans by Hereward the Wake. The more I wrote about 11th-century Ely, the more I wondered what it actually looked like. I knew that Ely had been an island, and I was having difficulty tracking where my characters were in relation to the original fens. So to help answer the question, I set about drawing a map of medieval Ely.

Including doing all the research, it took 200 hours to complete the map over an 8 month period in 2013. The original map is 1m x 1.2m and I had to make a workspace in the loft for all the materials, as it was too big to work on in the house!

Was this the first time you’d tackled a project like this?

The proper answer is yes. I do not have an artistic bone in my body, and made several attempts before ending up with the version you see. The eels in the border were particularly challenging (or should I say slippery!).

However, when I was a teenager in the mid 1970s, I spent an entire summer holiday recreating the map of Middle Earth from The Lord of the Rings. By coincidence, that is also 1m x 1.2m, and was drawn on a big piece of butcher’s paper! It hangs on the wall next to my map of Ely.

However, when I was a teenager in the mid 1970s, I spent an entire summer holiday recreating the map of Middle Earth from The Lord of the Rings. By coincidence, that is also 1m x 1.2m, and was drawn on a big piece of butcher’s paper! It hangs on the wall next to my map of Ely.

The Romans were the first to try to drain the Fens. How much evidence of their activities can still be seen in the landscape today?

Well, the Romans were first and foremost engineers, and they managed to tame many environments across Europe. But the might of Rome met her match with the fens! The landscape of the fens was too wild and impenetrable for the Romans to have any real success in their attempts to drain them.

However, the Romans did build several causeways to make travel easier, the most famous of which was the Fen Causeway, or Fen Road. This linked Denver, near Downham Market, to Peterborough, but it essentially was a road at the northern edge of the fens, which at that time would have been a coast road, as the modern coastline is many miles further north than it was in Roman times. Another causeway linked Cambridge with Ely, some of which is now part of the A10 trunk road and can be seen near Denny Abbey.

They also excavated the Cardyke (visible on my map). This canal system linked the Granta (now the Cam) to the West River and allowed movement of goods and people through the river system of the fens.

Since the marshes were drained in the seventeenth century it has obviously changed a great deal. How difficult was it to rediscover the medieval Fens?

It was harder than I expected. At first I simply tried searching online for a copy of how the fens would have looked, and that would have been sufficient for what I needed. But there were no definitive sources I could find. I also became aware that researchers had published material, but the information was not easily accessible.

What became apparent was that my task had two elements to it. The first was to try and understand how the land would have looked. This was relatively straightforward, as whilst the level of the water table has dropped since the fens were drained, the geology that created the “islands” has not changed at all (in other words, there has been no undue erosion of the landmass).

By far the most difficult part of the research was to try and understand how the waterways would have looked, and how they linked together. The river systems that people living in Ely today will recognise is very different to that of a thousand years ago. Today, the Ouse runs west to east and joins the Cam before heading North past Ely. The Cam (Granta) has not changed much since those times, but it came to light that the West River flowed east to west and joined the Great Ouse to head north to the left of Ely! This was a very different system to that seen today. The courses of the Ouse changed principally because of the two huge artificial drainage ditches that were constructed to the northwest of Ely (the Bedford Rivers), commissioned by the 4th Earl of Bedford in 1630 to help in the process of draining the fens.

By far the most difficult part of the research was to try and understand how the waterways would have looked, and how they linked together. The river systems that people living in Ely today will recognise is very different to that of a thousand years ago. Today, the Ouse runs west to east and joins the Cam before heading North past Ely. The Cam (Granta) has not changed much since those times, but it came to light that the West River flowed east to west and joined the Great Ouse to head north to the left of Ely! This was a very different system to that seen today. The courses of the Ouse changed principally because of the two huge artificial drainage ditches that were constructed to the northwest of Ely (the Bedford Rivers), commissioned by the 4th Earl of Bedford in 1630 to help in the process of draining the fens.

What sources did you use to delve into this lost landscape?

I used the resources of the British Library to look for the oldest maps of the area prior to the Dutch draining the fens in the 17th century. All maps of the area are thought to derive from a survey of the area carried out by William Hayward at the beginning of the 17th century. This map was destroyed in a fire, but it is believed that Sir Robert Cotton, a keen collector of fenland maps, had a copy made (The Cotton Map). It is an extraordinary document. Looking at the hand drawn map, you can see the lost Isle of Eels emerging from the fens, as if I was looking back in time.

I supplemented this information with a review of existing Ordnance Survey maps, using the 5-metre contour line to sketch out land that would have been above the ancient water table. In the British Library I came across a pivotal paper published by Major Gordon Fowler in 1934. This paper outlined the possible ancient watercourses of the area. Along with several other authors and notably the excellent Henry Darby, I pieced together how the rivers would have flowed around the island in Saxon times.

The final step was to add the main settlements that would have existed in 1071. For this I used a mixture of references from Domesday Book and the Liber Eliensis, the so-called Book of Ely, written in the 12th century by monks at Ely Abbey.

[NOTE: A full list of references can be found at the end of Rus’s article on the British Library’s blog.]

How much fieldwork did you have to do and what did that involve? How useful was it to be on the ground?

During the summer of 2013 I drove the back roads and lanes that criss-cross the island, making adjustments to my notes, extending the sweep of a hill, noting natural hollows in the ground, and removing the causeways and embankments that had been added much later. Without doubt, being on the ground helped add context to the map.

But for me, on a personal level, it was more than a matter of accuracy. Seeing the landscape allowed me to connect with the map, it helped guide my hand when I was back in my draughty cold loft, transcribing the information; it made the map live for me.

Were there any particularly unusual or surprising nuggets of information that you turned up in the course of your research?

Were there any particularly unusual or surprising nuggets of information that you turned up in the course of your research?

My discovery that the modern day Ouse had a completely different route and was not joined to the Cam surprised me. But to some extent, that was a matter of historical record, I simply needed the time to find the information.

However, some of the old books I read in the British Library gave vivid accounts of the fens in medieval times. The people were a breed apart; tough, independent, wary of outsiders. They wore eel skins to ward off illness and bad spirits. They would fight fiercely to defend their homes. The fens themselves were thriving with life, with bitterns, swans and eels. I read of Flag Iris, a beautiful carpet of flowers with a fragrant scent; but if a man stood on it, he would be sucked deep into the waters below. There was one account of a pod of whales that swam into the Granta from the sea. They became stuck in a small tributary and died. For many decades their skeletons were a reminder of the dangers of the fens.

So what did I do with all these nuggets? I am a writer, so I weaved them into my story, to bring it alive, to make it real.

How do you plan to use the map now that it’s finished?

Now that the map is complete (a copy of which I donated to the British Library), I can travel back in time to 1071 and see the Isle of Eels through the eyes of my characters. It has allowed me to be more credible when describing their adventures.

It is also my intention for the map to be part of the book, so that the readers can also see what Ely would have looked like in the eleventh century. Maybe one day, if my book is a success, the map will become as famous as the one of Middle Earth…