The ruins of St Andrews cathedral. At 119 metres (391 feet) in length, it’s the largest church ever to have been built in Scotland.

Being a historical novelist is all about bringing the past to life for a modern audience, so this conference seemed like the ideal chance to meet and share ideas with like-minded people from across the academic community who also happen to have the same love of the Middle Ages. And so I found myself in the company of 175 other delegates from 15 countries – some having travelled from as far afield as Australia, Korea and Canada – discussing how various aspects of the Middle Ages are represented today in literature, music, film, TV, climate change science and almost every other field imaginable.

I was there to deliver a paper entitled Representing the Middle Ages in Fiction, drawing upon my own experiences to discuss ways in which novelists might go about presenting their subjects in a historically responsible way. How rigorous should novelists be in their research? Can and should we hold them up to the same standards as professional historians? Accepting that a certain amount of invention and distortion is unavoidable in writing historical fiction, is there a certain point at which too much becomes unacceptable, and it descends into fantasy? What can historical fiction offer that non-fiction histories alone might ordinarily struggle to do?

The town of St Andrews, as seen from the top of the 12-century St Regulus’ Tower, which stands amidst the cathedral ruins.

I also had the good fortune to meet and discuss writing with Felicitas Hoppe, a German novelist and recent winner of the prestigious Georg Büchner Prize – one of the most prestigious German-language literary awards – who gave a plenary lecture about the challenges of adapting medieval romances into fiction. Other brilliant lectures included James Robinson from the National Museum of Scotland speaking about the similarities between the cults of medieval saints and those of modern celebrities; Bruce Holsinger from the University of Virginia talking about how an extract from the Icelandic sagas has found its way into debates about global warming; and Patrick Geary from the Institute of Advanced Study, Princeton, examining how medieval ideas of European ethnicity still have political currency today.

Those were just a few of the highlights from the conference. More on those, and on the rest of my findings from my time in St Andrews, in Part Two of my report, coming soon!

During the course of 2006-7, when I was first laying pen to paper on the early drafts of the manuscript that would become Sworn Sword, I was fortunate enough to read a number of historical novels that really inspired me. In recent weeks I’ve been revisiting a few of those novels, to see if they still hold the same fascination for me five or so years on, and whether with the benefit of more writerly experience I view them any differently now.

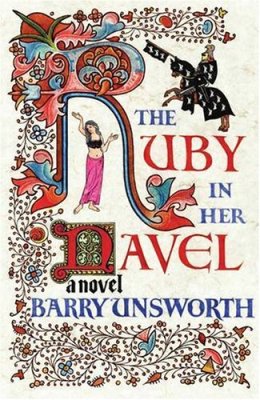

Among those books were titles by Bernard Cornwell, C. J. Sansom, and Robert Harris, set in periods ranging from Rome in the late Republic to Tudor England. Particular inspiration, however, came from The Ruby in Her Navel by celebrated British author Barry Unsworth.

Among those books were titles by Bernard Cornwell, C. J. Sansom, and Robert Harris, set in periods ranging from Rome in the late Republic to Tudor England. Particular inspiration, however, came from The Ruby in Her Navel by celebrated British author Barry Unsworth.

Longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2006, it’s set in mid-12th century Sicily in the reign of King Roger II, more than seventy years after the Norman conquest of the island, in a brief and peculiar (for the Middle Ages) period of toleration that saw various ethnic and religious groups – Normans, Italians, Saracens and Byzantine Greeks; Muslims, Jews and both Western (Latin) and Orthodox Christians – co-existing in apparent harmony despite the political fallout from the recent failure of the Second Crusade. More specifically, it’s the story, told in the first person, of a young would-be knight named Thurstan Beauchamp, who works as a purveyor of entertainments and occasional envoy and spy – for want of better terms – attached to the Diwan (Office) of Control in the palace administration.

What unfolds is a tapestry of competing nobles, royal officials, churchmen, all with their own ambitions and plans for advancement: a shadowy assortment of real and imagined foes with the means to destabilise King Roger’s realm from within and without. Through those tangled webs the trusty, proud and not a little naive Thurstan makes his way, but soon he finds himself embroiled in a plot that threatens to destroy all he holds dear. There are the added complications, too, of the two women in his life: Thurstan’s childhood sweetheart Lady Alicia, recently widowed and returned from Outremer; and the exotic and enchanting Anatolian belly-dancer Nesrin, whose troupe he employs to entertain at the king’s court.

This a carefully crafted portrait of an unusual place and time in history. Unsworth’s descriptive powers and his ability to evoke all the senses are second to none. His wide-ranging settings – from the richness of the palace at Palermo or the elaborate gardens at Favara to the dusty streets of the port of Bari in Apulia – are desribed in vivid detail. The Ruby in Her Navel showed me the power of historical fiction to evoke the spirit of a distant age and to bring the past to life, and even on a second reading it did not disappoint.

Thurstan’s world is a complex and uncertain one in all sorts of ways: politically, religiously and morally. By choosing to tell the story in the first person from his perspective, Unsworth allows us to glimpse something of the various dark forces that are at work without ever fully comprehending them, as well as to engage on an intimate level with the realities of life in that age and the burning issues of the day. It’s skilfully done, and while Thurstan is undoubtedly a flawed hero – vain, overly confident in his own abilities, and too trusting by half – he nevertheless manages to be a character with whom it is possible to sympathise.

For those with an interest in medieval fiction, there are few novels I can recommend more highly. The Ruby in Her Navel remains one of my all-time favourites.

NOTE: In an unexpected and very sad turn of events, the day after I posted this review (8 June) the news broke that Barry Unsworth had died at the age of 81 in Perugia, Italy. Even though it wasn’t my intention, I hope that my above words will stand as a tribute, however small, to his life and to his qualities and skill as a writer. He will be sorely missed by his many fans.