Based on real-life events, Sworn Sword tells the story of the great rebellions that swept England in the years after 1066, as seen through the eyes of a Norman knight named Tancred, who seeks vengeance after his lord is killed by English rebels.

Published by Sourcebooks Landmark, it’ll be available from all good bookstores and, of course, online as well, in both hardcover and eBook editions. Here’s the full synopsis:

January, 1069. Less than three years after the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and the death of the usurper, Harold Godwineson, two thousand Normans march in the depths of winter to subdue the troublesome province of Northumbria. Tancred a Dinant,a loyal and ambitious knight, is among them, hungry for battle, honor, silver, and land.

But at Durham, the Normans are ambushed in the streets by English rebels, and Tancred’s revered lord Robert de Commines is slain. Badly wounded, Tancred barely escapes with his own life. Bitterly determined to seek vengeance for his lord’s murder, the dauntless knight quickly becomes entrenched in secret dealings between a powerful Norman magnate and a shadow from the past.

As the Norman and English armies prepare to clash, Tancred uncovers a cunning plot that harks back to the day of Hastings itself. If successful, it threatens to destroy the entire conquest-and change the course of history.

This stunning debut sweeps readers into a ruthless, formidable world, where violent warriors seek honor in holy places and holy men seek glory in dark deeds. As the two opposing forces battle for conquest, the fate of England hangs in the balance.

Battles and betrayals abound, and there’s also a touch of romance, too – something, I hope, for everyone. And if that’s whetted your appetite, here’s the first chapter to give a further taste of what’s in store.

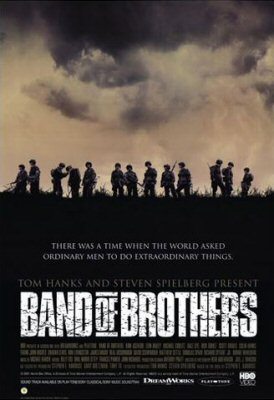

Promotional poster for the Second World War miniseries Band of Brothers, which was originally broadcast in 2001.

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother …

– William Shakespeare, Henry V, Act IV Scene iii

The idea of the “band of brothers” is central to Sworn Sword. The opening encounter at Durham sees Tancred’s conroi (the basic Norman cavalry unit, usually composed of around twenty men) shattered and his lord killed at the hands of Northumbrian rebels. Only two of his fellow knights, his close friends Eudo and Wace, survive to help him carry the stain of that defeat. The close group of warriors he once belonged to, who ate and trained and joked and fought together, is no more.

What happened to the real survivors of Durham is not recorded in the primary sources that mention the battle; indeed it is rare that the chronicles offer much by way of insight into the feelings of the people whose fates they record. Still, it is possible to imagine the grief and guilt and sense of loss those survivors had to bear, and the thoughts of revenge they must have harboured.

To capture a full sense of what it means to be part of such a tight-knit combat unit, I sometimes look to similar depictions elsewhere in fiction. One of the best portrayals I’ve come across is in the TV miniseries Band of Brothers. I first saw this series when it was originally shown in 2001, and watched it a second time a few years back when I was in the early stages of writing the novel that would become Sworn Sword.

With the second book, The Splintered Kingdom, now completed and my thoughts already turning to the next instalment of Tancred’s story, I went back to view the series on DVD again this week. Each time I’ve come to it with new eyes, and each time I’ve been able to take something away from it that either adds to my understanding of the hardships of war, or gives me ideas for fresh avenues to explore or new ways to depict the ongoing conflict that was the Norman Conquest in my writing.

The “band of brothers” of the series’ title is Easy Company of 2nd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment in the 101st Airborne Division of the U.S. Army. Over ten episodes we follow the exploits of the various characters – all based on real-life individuals – who make up the company, from their early training to Operation Overlord, and from there through Operation Market Garden and the Battle of the Bulge to the occupation of Germany at the end of the war.

The over-arching narrative of the 1944-5 campaign in Western Europe bears some similarities to that of the Norman Conquest. The series of operations which led from the Normandy landings to Berlin was long and arduous; progress was sporadic and frequently subject to German counter-offensives. Just as D-Day was only the beginning in June 1944, so the Battle of Hastings proved merely the opening engagement, albeit a highly significant one, in the Conquest.

Even though nearly 900 years separate the Second World War from my own period, there’s still a lot that can be learnt from Band of Brothers, not least regarding the experience of war and the psychology of those individuals who make it their business to fight. It’s fascinating to follow the journeys of the various characters and see how they each respond to the situations they find themselves in, and face up to challenges both physical and emotional.

We see green and untested volunteers develop into seasoned and skilled campaigners. Some appear to be natural warriors and born leaders, and find themselves in their element from the start, while others take time to find their feet. Some are strengthened by their experience of the war; others find themselves consumed by it, to the point where in order to make it through they sacrifice some of their humanity. One thing they have in common is that they are all changed by what they have seen and done.

War exacts its toll upon the individual in different ways, as I hope The Splintered Kingdom will show. As the battle for England intensifies and the kingdom falls under siege on all sides, the Normans’ grip on their hard-fought gains grows ever weaker, and in the middle of the struggle Tancred finds his resolve put to the test as never before.

This week I returned to the place where Tancred’s story begins – to Durham, where the city’s annual Book Festival has been taking place this month. An enthusiastic audience joined myself and my event host, Dr Giles Gasper, lecturer in medieval history at Durham University, for a discussion about Sworn Sword and its connection with the city.

One of the questions I was asked was why I chose Durham in particular as the place to begin the novel. In fact the battle that forms the opening chapters was a real-life event that took place on or around 28 January 1069, and it’s spoiling none of the plot to say that it marked a significant turning-point in the story of the Conquest. Indeed this was the biggest defeat that the Normans had suffered since arriving on these shores more than two years previously.

Around Christmas 1068, William the Conqueror appointed Robert de Commines, Tancred’s lord, as Earl of Northumbria, the only part of England that had thus far refused to acknowledge him as king. Together with his army – the sources disagree on exactly how many men – Robert marched to subdue the recalcitrant northerners and take the province by force. Soon after arriving in Durham, however, the earl and his forces were routed in a surprise attack under the cover of darkness. The Normans were cut down in the streets and Robert himself was killed. There were few survivors.

View of the tower and north transept of Durham Cathedral.

Walking around the city on my visit there this week, I was reminded just how dramatic a location Durham is, and how its very geography makes it a fascinating setting for a battle. The castle and the cathedral that nowadays dominate the skyline had not yet been built by 1069, but the peninsula on which they are built would have made this a naturally defensible site, protected on three sides by water and by steep inclines that would make any direct assault difficult except from the north. While there is little explicit evidence for any fortification on the site before then, to my mind it seems likely that a stronghold or fastness of some kind must have existed, as I have suggested in Sworn Sword.

Whether or not such defences existed at the time, the very fact that the Northumbrians were able to defeat the Normans here was by all accounts an impressive achievement, and a famous victory. Conversely, to the Normans this would have been seen as a major setback to their conquest of the north. The loss of so many men in one night would not only have dented their confidence but in addition must have placed a very real strain on their defences, especially once the enemy began their southwards march not long after.

The Durham connection was just the starting-point of a great discussion about the Norman Conquest and historical fiction. Topics ranged from the use of Old English place-names in the novel to getting inside the medieval mind, the importance of research and site visits, and my plans for future novels in the series. I certainly enjoyed myself and I hope that my audience did too.

Many thanks to all those involved in the organisation and smooth running of this year’s Festival. Particular thanks also go to my host for the event, Dr Gasper, who generously gave his time after the talk to give me an exclusive tour of Durham Castle’s Norman chapel, which is normally off-limits to the public. One of the earliest stone chapels of its kind known to have been built in England, it is thought to date from the 1080s when it was attached to the house of the Bishop of Durham, who probably used it as a private place of worship. It was a privilege to be allowed access to such impressive architecture, and an unexpected bonus on my northern travels.

I’m hoping to be back in Durham at some point in the New Year, and in February I’ll also be visiting York, the centrepoint for much of the action in Sworn Sword, where I’ll be giving a talk at the Jorvik Viking Festival – more details to follow in due course. Keep checking my Events page for further information about all my upcoming appearances.

*

The Durham Book Festival runs until tomorrow, Sunday 23 October, with further events for young writers continuing through half-term week to Friday 28 October. For more information visit the Festival website.

Norman knights led by Bishop Odo of Bayeux riding into battle under the papal banner. Image taken at English Heritage's annual Battle of Hastings re-enactment.

One of the most common questions that readers of Sworn Sword ask me is why I chose to write from the Norman perspective, rather than that of the English, as might be expected. In fact this was a decision that I made very early on in the novel’s development, when it was little more than a bundle of research notes and half-formed plot ideas.

I had long been fascinated by the Conquest, and I knew that what I wanted to write about were the years that followed the Battle of Hastings: a turbulent period as the Normans fought to consolidate their gains and subdue a country rife with rebellion. (The story of one of those rebellions, led by the dispossessed prince Eadgar, forms the backbone of the novel.) However, while the theme of the tragic-heroic struggle of the Anglo-Saxons against their foreign oppressors seemed to me very familiar, the Norman version of events was not generally as well known. Straightaway, then, I started to think about giving the tale of the Conquest a fresh twist, by telling it from the “other” point of view.

Every story has two sides. One man’s freedom fighter is another man’s insurgent. These sayings are so familiar as to have almost become clichés. By blurring the traditional distinction between the “good” English and the “evil” Normans, I hoped to show the period in a different light, to challenge readers’ sympathies and preconceptions. So far as I could see it was an angle that few authors had taken before, which made this a subject ripe for exploration.

Even so, to get the modern reader on the side of the foreigner is no easy task. Why this should be isn’t completely clear. After all, it goes almost without saying that the Englisc of the eleventh century are not at all the same people as the English of the twenty-first. Moreover, were it not for the Normans, we would not speak the language we do today, our systems of law and governance would be entirely different, as so too would our cultural heritage, since all are based on the foundations that they laid. The world we live in today owes as much, if not more to the Normans than it does to the Anglo-Saxons.

None of that, of course, is to deny that the Norman invasion was a brutal affair, or that it resulted in tremendous suffering for many thousands of people. In particular the campaign later known as the Harrying of the North, by which King William devastated Yorkshire in the winter of 1069-70, is testament to that. Nonetheless, to suggest that the Normans were universally bad men would be a gross oversimplification. Undoubtedly some came to England purely for self-serving reasons – out of desire for land and wealth, blood and glory – but I believe that many were also complex human beings who truly believed in the righteousness of their cause.

William of Normandy’s case for war in 1066 was built on two main pillars. The first of those was that the claim that he had been promised the succession by King Edward the Confessor in 1051. The second was that in c. 1064 Harold Godwineson had sworn on holy relics to uphold his right to the throne: a promise that he had subsequently broken when he himself seized the crown upon Edward’s death in January 1066. As far as the invaders were concerned, then, Harold was a perjurer and a usurper who had no right to the English crown. Worse than that, he was effectively made an enemy of God after Pope Alexander II gave his approval to William’s proposed invasion and sent him a consecrated banner under which to fight. To a Christian knight riding in the Conqueror’s army, there would have been little question that he was on the side of justice. William was the rightful king, anointed by God, and any who rose against him were to be crushed.

However, as Tancred finds out over the course of Sworn Sword, it is often difficult to tell who is right and who is wrong in any given situation. There are times when men will betray their principles in noble causes; on other occasions they will hold steadfastly to them even if it means the destruction of all that they hold dear. Englishmen will fight in the service of Normans and vice versa, to the extent that the “sides” become blurred and it becomes harder to talk about this period as a simple conflict between the two peoples, still less as one of good versus evil.

In reality the Conquest was a complicated and morally messy affair, and by offering a different perspective this is what I hope to show in Sworn Sword.