In a way, it’s reassuring to know that, amidst the pandemic-induced tumult that has engulfed the world, The Archers – that famous Radio 4 institution – remains a coronavirus-free zone. Life in the fictional community of Ambridge continues miraculously as it ever has done, sans the lockdown and self-isolation measures witnessed by the rest of us.

For now, at least. Enough episodes have been recorded that the long-running radio soap will keep going in its current format until the end of this month, with (presumably) no references to the dreaded c-word being made during that time.

From May, however, all that will change. The BBC’s recent announcement reveals that coronavirus will indeed begin to feature, “in a way that the programme’s many loyal listeners might expect”, and that the format will be different, too, with individual cast members recording their parts from home studios.

But with fiction in this case taking so long to catch up with reality, there are some important questions worth raising about the relationship between the two. To what extent do we expect fiction to reflect the real world that we see around us? How important is it that fiction – whether in the form of radio drama, film and television, or novels – keeps up with rapidly developing current events?

We are, of course, primed to accept a certain level of artificiality in our fictions. We know that there is no Ambridge, no Felpersham, no Borsetshire. We know that these places – and their associated characters – exist in a setting which is not actually rural Britain but a simulacrum, an amalgam of rural Britain, and not even that but rather than insulated pocket within that imagined world.

We take these things as given. We readily accept that The Archers represents an alternate or parallel reality, a pretence, an illusion. And yet, as series editor Jeremy Howe says, one of the programme’s aims to offer “a picture of the way we live now in rural England”. That is to say, if it doesn’t bear at least some relation to the texture of real life – if it does not feel authentic – then it will not satisfy its listeners.

The BBC’s press release reminds us that topical events such as England’s progress during the World Cup have often been added to scripts, not only keeping the programme up-to-date but also sustaining the sense of authenticity required in order to render this fictional world believable.

But where does one draw the line? How much of the real world should be permitted to intrude upon the lives of these characters? Which real-world events are important enough that they must be included, and which can be disregarded? More widely, we might well ask: what do we want to see from the fiction that we consume – both during the current crisis and otherwise? Is its role to represent and respond to reality, or to offer a diversion from it?

“For nearly 70 years Ambridge has been a haven for our audience, and so it continues to be,” Howe says. “Whilst Coronavirus might be coming to Borsetshire, listeners can still expect The Archers to be an escape [emphasis added].”

On how he intends to reconcile these two apparently divergent aims, however – to provide both “a picture of the way we live now” and “an escape” – he remains tight-lipped. It will be interesting to see what course the programme steers over the coming months.

The reason these questions have occupied my attention this week isn’t because I’m a devoted listener of The Archers (sorry, Ambridge fans) but because many of the same issues arise in my own work and research, albeit in relation to the past rather than the present.

What is it that gives a historical novel authenticity? How closely must a novel set in the past adhere to real events, cultures, social customs etc., in order for it to qualify as “historical” fiction? Would it be better if we considered all works set in the past to be essentially a form of counterfactual (“what if?”) narrative – imagined, possible versions of events that bear some resemblance to reality, without necessarily making any claim to represent it?

These are the sorts of questions I’ve been asking over the past two-and-a-half years during the course of my PhD at the University of Nottingham, and which I’ve been trying to answer while working on my latest novel and the thesis that accompanies it.

Whether we’re writing about the past or the present or the future, there will always be a natural tension between fiction and reality. That said, imagining how things could be different either now or in the future, or how they might have happened (or happened differently) in the past, is what fiction has always excelled at. Moreover, the power of these alternative realities to contextualise our present situation – and allow us to see it in a different light – should not be underestimated.

Would it be a problem if The Archers were to continue blithely on its own timeline – if it remained pandemic-free indefinitely? I wonder.

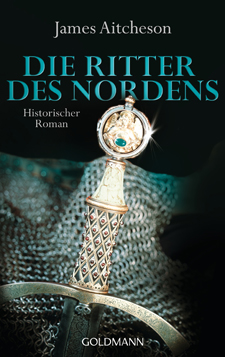

Why is there no historical note in The Harrowing? A number of readers have asked me this over the past two-and-a-half years since the novel was first published. It’s a question that, I’ve come to realise, goes to the heart of what I believe historical fiction is all about. In this post I’ll explore my decision not to include a note (no, it wasn’t down to laziness) and how this fits into my wider philosophy as regards writing fiction set in the past.

In all three of my Conquest novels, first published in the UK between 2011 and 2013, the final chapter or epilogue is followed by an appendix in which I contextualise the story by exploring the real-life events, cultures and individuals who inspired it. In this very short essay – never more than around 2,000 to 2,500 words, or roughly 5 to 6 pages in the printed book – I would offer an insight into some of my preparatory research and the primary sources I’ve relied upon, deconstruct the novel’s relationship to the historical record, and highlight particular occasions where the truth is uncertain, where I’ve used artistic licence, or where I’ve deliberately introduced a fictional element.

The historical note, or author’s note, or afterword – whatever one wishes to call it – is these days a standard element of the historical novel, especially at the commercial end of the market. It’s my general impression that it’s slightly less common at literary end, although by no means is it unheard of. Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood and Burial Rites by Hannah Kent are two prominent examples of novels containing such a note that spring to mind, being as they are conveniently placed on the shelf above my desk as I write this piece. Needless to say, historical notes vary considerably in length: in the case of Burial Rites, it’s a mere three pages; by contrast, C.J. Sansom concludes his latest Shardlake novel, Tombland, with a 60-page essay.

The key reason why I elected not to write a historical note for The Harrowing was my desire to let the story speak for itself. I won’t give any spoilers here, but suffice it to say that the novel finishes on a touching moment, balanced between optimism and tragedy, and with a complex swirl of emotions in play. It felt appropriate to give the reader space to digest the resolution and decide how they feel about the events described, rather than allow the authorial voice to intrude and puncture the atmosphere. Closing the book with Tova’s words rather than my own felt more respectful towards her, the other characters and the journey they have completed – and on which the reader has followed them.

The end, in this case, really is the end. There is no story beyond the story; the novel’s meaning is not complicated or revised by the addition of an appendix that seeks to provide a broader picture, or that brings the reader back to ‘reality’. Demonstrating the narrative’s historical underpinnings would, in this case, have severely undermined what I was trying to achieve.

After all, my rationale for using fiction rather than non-fiction to explore the Harrying of the North – the devastating campaign that saw the Normans lay waste to vast tracts of northern England during the winter of 1069–70 – was that the bare facts and figures seemed insufficient to convey the true horror of this episode. No first-hand accounts of this event have been handed down to us by its victims; their stories have been lost forever. The only way to give voices back to those people, to make sense of their experience, to see them as individual human beings and to rescue them from being relegated to mere statistics, was through fiction.

For that reason, to fall back at the end of the book upon statistics, dates and sources relating to the Harrying of the North as justification or context for the narrative would have seemed to me like an admission of defeat. It would have diminished the creative process, the act of imagination and the attempt to forge an emotional connection with the past, by implying that the story was not robust enough to stand on its own merits.

Here we come to the crux of the matter. In 2017, in an interview at the Oxford Literary Festival, Hilary Mantel criticised her fellow historical novelists who, in her words, ‘try to burnish their credentials by affixing a bibliography’. She said: ‘You have the authority of the imagination, you have legitimacy. Take it. Do not spend your life in apologetic cringing because you think you are some inferior form of historian. The trades are different but complementary.’

The historical note, it is true, offers novelists a chance to set the record straight. In it we can demonstrate the breadth and depth of our reading. In this way, we are arguing for the right to be taken seriously – a natural impulse. But by doing so we are actually asking to be judged by the standards of a different discipline, and so inadvertently diminishing our own status as writers. It is a defensive act rather than a positive statement of our own distinct and legitimate authority.

Novelists, it should go without saying, are not historians. Historical fiction, no matter how well researched, is not history. Its value as a literary genre lies elsewhere. Where? Well, that’s a weighty subject in its own right, and one that I’ll save for another day and another blog post. Suffice it to say for now that historical fiction is the product of a different set of skills, and it is those skills – the craft and technique that we have each developed as writers – that we should be celebrating and drawing particular attention to.

Historians and other scholars are required to show their workings if they are to build a convincing argument. For artists it is different: what matters above all is the final piece. I would much rather these days that my work speaks directly to the reader. That’s why, for me, the historical note has become redundant: not because I have nothing to say, but because to say it would risk dispelling the magic. Yes, it’s always fun to see how the trick is done, but we revel more in the mystery. Less, as so often, is more.

For both narrative and philosophical reasons, then, there is no historical note in The Harrowing. Will there be one in my current work-in-progress? Probably not. That’s not to say I can’t envisage a future novel that might be enhanced by such a note. For now, though, I’m content to keep separate my twin identities – the novelist and the medievalist – and to let them work freely and independently in their own respective ways.

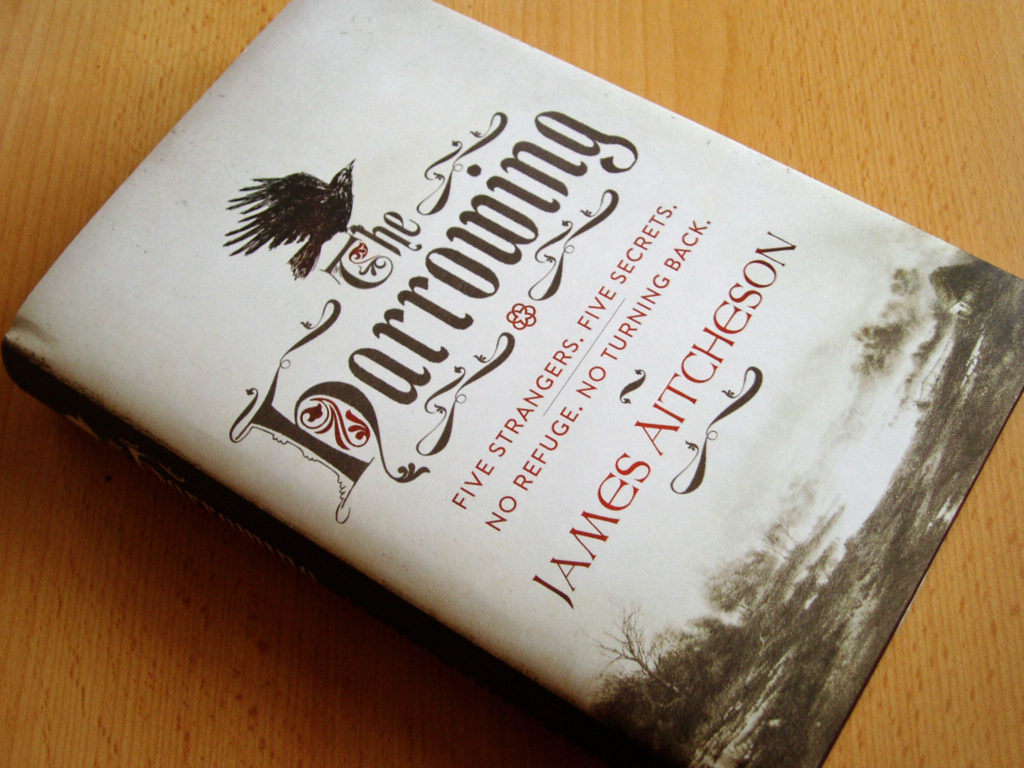

This summer, after writing professionally for eight years, I finally penned my very first short story.

To some readers of this blog this may come as a surprise. Creative writing guides often advise those getting started to begin with short fiction: it is regarded by many as part and parcel of the traditional apprenticeship that writers must undergo. The short story, according to the theory, is the training ground where we’re supposed to hone our craft, to find our voice, to tighten our prose, to learn the skills that will allow us to tackle our bigger projects.

The beach at Manorbier, Pembrokeshire, pictured here on a grey and chilly April day in 2017, offered the inspiration for one of my short stories this summer.

There’s a certain logic to this school of thought. A novel is a mountain: to scale it takes considerable planning and preparation followed by a long and arduous climb to the summit, punctuated by unforeseen obstacles that aren’t always visible from base camp. And the metaphorical descent can be just as tricky, as you return over ground already covered: editing, reassessing and rewriting, often repeatedly. The prospect is daunting, and there are any number of reasons to give up along the way. The gratification that comes with completion can seem forever out of reach; it’s easy to misinterpret the constant struggle as a sign of failure.

The short story, on the other hand, offers a quicker route to that sense of gratification. For the novice, the knowledge of having completed something is invaluable: it is validation of one’s own ability. Success breeds confidence, and confidence breeds success. It’s a virtuous circle, or at least that’s the principle. It enables experimentation without risk.

But writing short fiction has its own unique challenges. Few of us read it, and even those of us who do tend not to consume it in the same quantity that we consume novels. If we don’t read it, how can we expect to be able to write it? When in 2006 I started out on my writer’s journey I certainly hadn’t read enough short stories to understand their form and structure. I did attempt to write a few, but without a clear idea of what I was trying to achieve, and so I soon abandoned them. What I wanted was to write a novel, and so with the single-mindedness of youth I set out from the beginning to do exactly that.

It’s only now – after an MA in Creative Writing, four published novels and now the first year of a PhD – that I feel I understand my craft well enough that I’m able to graduate from the novel to the shorter form. The short story is more technical, more succinct; it requires greater precision of language and phrasing. Every word matters. What is not said can be just as important as that which is made explicit. Working out how best to exploit the negative space around the words can reap immense rewards, but takes time.

A short story doesn’t obey the same conventions as its longer counterpart. It can be a puzzle for the reader to crack; it can pose questions without the pressure of having to offer resolution. In its very brevity it offers complexity. The process of writing one is certainly shorter, but not necessarily any easier than writing a novel. It requires skills that my younger self twelve years ago simply did not possess.

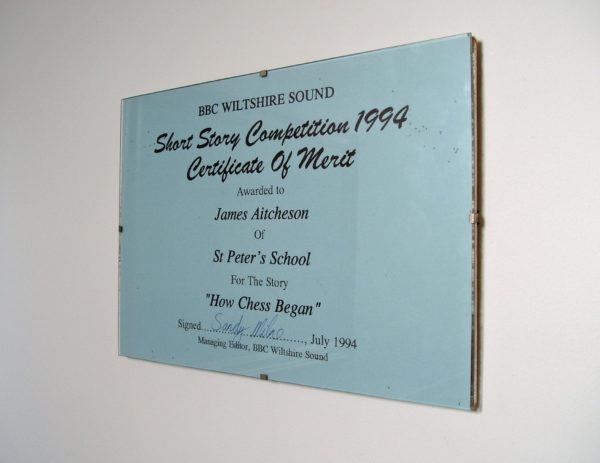

Disclaimer: in saying that I haven’t written a short story before, I’m obviously not counting the one I wrote when I was eight, which won me this lovely certificate from BBC Wiltshire Sound.

For me, writing short stories this summer has offered me a chance to experiment with voice, form and prose technique, to break away from my usual habits and comfort zones, and to test ideas for my bigger project – the novel that forms the heart of my PhD thesis. It has been liberating, allowing me to expand my horizons beyond historical fiction and try out other genres for the first time in years. (Not that I’ve ever seen myself purely as a historical novelist: that’s simply where my career has happened to take me so far.)

These past few months have been some of the most creative I’ve experienced, and the stories I’ve produced are, I believe, some of my most challenging and imaginative work. As I turn now back towards thinking about the novel, I feel reinvigorated but also increasingly aware of the possibilities of the longer form – and increasingly confident in my own ability to achieve them. More than ever I feel I’m on the cusp of something very exciting: I’m redefining myself as an author.

Get ready for James Aitcheson 2.0.

This week I wrote.

That probably seems like a fairly unremarkable thing for a novelist to say. But in fact this was the first time since last summer that I’d produced any substantial creative work at all.

Sure, I’d scribbled down musings from time to time: a phrase; a sentence; sometimes as much as two sentences in a row. I’ve put together a quick-fire story in ten minutes as part of an exercise during a writing workshop that I led recently.

What I hadn’t done in over six months was spend a full day at my computer engaged with my current novel. In fact, for most of 2017, I deliberately didn’t write, or did so only intermittently. My total word count for my work-in-progress amounted to not much more than 10,000 words – that is to say, roughly around 30 pages.

I was a writer who wasn’t writing.

Detail from the ceiling of St David’s Cathedral, St Davids (Pembrokeshire). Photograph taken during the writer’s retreat I went on in spring 2017.

Of course, there have been a few mitigating circumstances. I was busy with other things: firstly preparing to begin my PhD at the University of Nottingham, and then, from the autumn onwards, launching myself into my research, which has taken me down some fascinating avenues. (Look out for more posts about my research coming soon.) But the main reason for this extended break was simply that I needed the time to recharge my creative batteries.

By that point I’d been writing consistently for over a decade: I began working on my first novel, Sworn Sword, shortly after I graduated from Cambridge in 2006. Traditionally I’ve tried not to take very long between finishing one novel and starting the next – often no more than a couple of months. It always seemed like the best way of overcoming the fear of the blank page, and gave me a continuing sense of purpose.

What it’s meant, though, is that there’s rarely been a moment when I’ve not had one project or another actively underway. In ten years, I hadn’t allowed myself the chance to step back and think more broadly about my creative direction and what I’m looking to achieve.

Hence why I decided for once not to pitch myself into this latest novel with the same single-mindedness, but instead to let it evolve gradually. In fact, the most important imaginative work I did in 2017 was away from the computer, as I refocused my energies.

I ventured out into the field to explore the history embedded within the urban and the rural landscapes: castles, cathedrals, abbeys, churches, palaces, you name it. I invested in a replacement for my aging 2003-spec digital camera and experimented with photographing these sites, searching for new ways of looking at them and the world in general.

Odda’s Chapel, Deerhurst (Gloucestershire): a rare example of a surviving late Anglo-Saxon church, and the destination of one of my many historical field trips in 2017.

Armed with notepad and HB pencil, I sought out the ancient and medieval collections in museums across the country, and made rough sketches of the artefacts I saw: whatever inspired me, however magnificent or mundane.

I thought about writing, even though I was doing very little of it. I went on a retreat, and even though it wasn’t as productive as I hoped, I came back re-energised. I spent more time than usual in the company of other writers, talking with them about the challenges, joys and frustrations of the creative process, and revelled in that sense of community. (Writers, in my experience, tend to be solitary creatures by necessity rather than by nature.)

I read books by authors I’d never encountered before, in all sorts of genres: historical fiction; memoir; SF and fantasy; young adult; contemporary; short stories; magical realism. All the while I continued to make reams of notes for my work-in-progress – gems of insight that I could add to my treasure hoard.

When I finally came back to the novel this week, having not looked at it – or those extensive notes – for several months, I saw it at once in a new light. To put things into perspective: those 10,000 words from last year were already, in my view, a cut above anything I’d ever produced before. In purely numerical terms it might not have amounted to much, but technically and conceptually, I felt I’d made an enormous stride forward.

Once I set to work, though, I was quickly aware of how often the 2018-me was bringing out the red pen for paragraphs that the 2017-me had considered brilliant. Even though I hadn’t been actively exercising my writing muscles, my expectations had evolved. I had raised the bar; I’d become more demanding of myself, not to mention more confident in my own abilities.

Detail of the oldest castle doors in Europe, at Chepstow Castle (Monmouthshire). Photograph taken during another of my many historical field trips in 2017.

The revised draft that eventually emerged was a considerable improvement in almost every aspect: better control of voice; greater precision of imagery; a more tightly worked approach to dialogue. And this made me think.

Is it possible to become a better writer by not writing?

From the very beginnings of our literary careers, we authors put pressure on ourselves to keep busy. How-to guides on getting started in creative writing often stress the importance of establishing a routine: making it a familiar habit. Indeed, the most common piece of advice I give to aspiring writers is simply to practise, and then to practise some more. There’s no great secret to it: the more you write, the better you’ll get.

For professional novelists, too, it’s easy to feel that if you’re not actively working on something, you’re not being productive. Readers, editors, booksellers and fellow authors are all eager to know not just about the current project, but also what’s next in the pipeline. (Will there be a sequel?) And, of course, time is money: if you’re not writing, you’re not earning.

At some point, though, it’s worthwhile taking a step back. If you’re to take your craft to the next level and produce something truly original, it makes sense to pause once in a while. Only by gaining some distance from the nitty-gritty can you see the bigger picture.

Don’t be a slave to your manuscript! Give your writing the room it needs to breathe. Take stock of what you’ve achieved so far. Think about how you might do things differently next time round. Consider new approaches, new ways of challenging yourself.

Hailes Abbey (Gloucestershire): a Cistercian monastery founded in the mid-13th century by Richard, Earl of Cornwall and younger brother of Henry III.

Reflect. Refresh. Get out for a bit. See the world. Read more books. Try your hand at another creative discipline. Open yourself up to new experiences. Do anything but write, at least for a little while.

Most importantly, by stepping back you allow yourself to recapture the passion, energy and ambition that made you want to write in the first place.

You owe that to yourself. And, in the long run, it’ll be worth it.

As many of you who follow me on Twitter and Facebook will already know, later this month I’ll be beginning a brand new chapter in my literary career. In just a few weeks I’ll be starting my PhD in Creative Writing at the University of Nottingham, thanks to an AHRC-funded studentship from the Midlands3Cities DTP.

The PhD will see me explore the boundaries of historical fiction and magic realism. I’ll be looking at medieval concepts of the otherworldly and supernatural in sources ranging from Beowulf to the Icelandic sagas, and using my findings to inspire and inform a novel set in medieval England that incorporates fantastical themes. It’s something of a departure in style and subject matter from my recent work, and I’m looking forward to delving into some of the weirder and more wonderful aspects of life in the Middle Ages.

Lately I’ve found myself thinking back to the autumn of 2007, just as I was embarking on a similar adventure with the MA in Creative Writing at Bath Spa University, where I began to develop the manuscript that eventually became Sworn Sword. I’d been writing in my spare time for several years, but I’d never before taken a formal course in the subject. Like everyone else, I was hoping it would be my first step on the journey towards seeing my name in print, but at that point publication, if I’m entirely honest, was still a distant dream.

Instead what most excited me about the MA was knowing that I had a whole 12 months ahead of me to develop my writing in a nurturing environment where experimentation was actively encouraged. The sheer energy of our cohort was infectious; it didn’t matter that were each working on wildly different projects, across every conceivable genre and in all manner of prose styles. We all knew the same joys of fiction-writing, and we all had the same goals: to learn and to improve.

Bath Spa University’s picturesque Newton Park campus. In the distance is the castle, where I enjoyed many a creative writing workshop during the MA.

Now, as I prepare for this next stage in my literary career, I find that same excitement returning, in a strange reflection of that autumn ten years ago. That’s not to say, of course, that I haven’t enjoyed the process of writing four novels in the meantime: each one has been an exciting, sometimes terrifying, frequently frustrating, but always hugely rewarding adventure. But that raw passion and energy for the creative process – the thrill that comes from venturing into the unknown, exploring new horizons and discovering as-yet-untapped potential, without the burden of expectation – is something I’ve not experienced since I was a novice writer. It bodes well, I think, that I’m rediscovering those feelings now.

I’ve often said that it would have taken me ten years to learn on my own what I learned in a single year on the MA. The course transformed my prose and I emerged from it armed with the skills I needed to turn my ideas into a fully fledged novel, having opened up avenues that I’d never previously considered. Partly that was due to the support I received from tutors; partly it was the result of the considered and constructive feedback from my peers; partly it was down to self-reflection and intensive drafting, redrafting and studying.

As well as the strides I made creatively, I also made friendships to last a lifetime. I still meet regularly with many of the other writers I met on the course, to review each other’s work over coffee and cake: this has been without a doubt the most valuable legacy of the MA. I had no idea when I started just how big an influence it would prove to have on my life, and it makes me wonder what lies in store for me over the next three years…

Another door opens… the gatehouse at Newton Park, Bath Spa University.

I’ve no doubt that the PhD will be a different beast: more self-directed, more research-focussed, it will require me to use different skills, and to develop some new ones along the way. But if I can recapture and hold on to that spirit of ’07, I hope to be able to match the progress I made that year, and even surpass it. To infinity – and beyond!