Recently I came across an article from Londonist, the online magazine, that featured a map of Anglo-Saxon London drawn by Matt Brown. It’s a terrific piece of work that depicts the geography of the area during the early Middle Ages and gives a sense of the sheer extent of the modern city. If you haven’t seen it yet, it’s definitely worth checking out. You can even download the full map to view offline.

On Thursday evening I posted a link to the map on my Facebook page. The following morning I found out that it had been shared by 19 people and reached an audience of 1,880. And that was just the start.

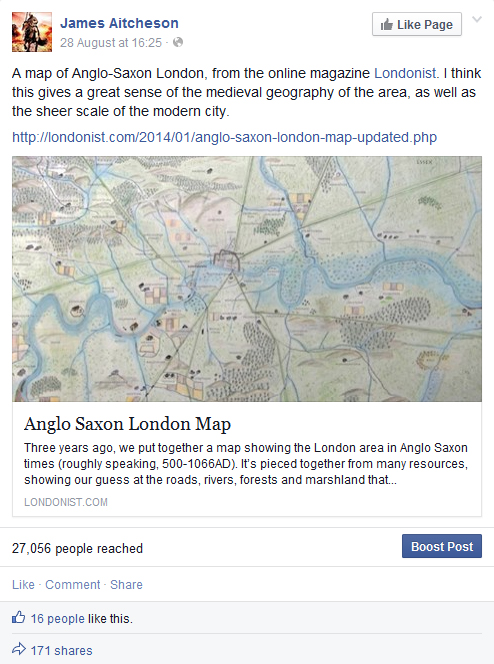

At the time of writing this article another two days later, the link has so far been shared no less than 171 times, and has been seen by more than 27,000 people on Facebook (see screengrab below).

Screengrab taken from my Facebook page (31 August 2014) of the original post that included the link to Matt Brown’s map of Anglo-Saxon London.

In the grand scheme of things, maybe 27,000 isn’t a lot. What was impressive was the speed with which the link spread, firstly as my own followers shared it, and then as it was passed on by their friends, and their friends in turn, with people adding comments at each stage as they located places where they’d lived or grown up.

What’s great is that there are obviously a lot of people out there who are interested in London’s history. Not only that, but everyone who shared the link clearly saw within the map a personal connection that brought the history to life and gave it meaning for them.

For anyone who’s interested in finding out more, Matt’s written other articles for Londonist exploring how London’s rivers and boroughs got their names, which are well worth a read. (Clue: most of them derive from pre-Conquest, Old English roots, and some are older even than that.)

And I’ve written my own piece on the history of Anglo-Saxon London: a whistlestop journey through the centuries, following the city’s evolution from the end of the Roman period to the construction of the Tower of London after the Norman Conquest.

Hot on the heels of last week’s addition to Tancred’s England, my historical guide to the kingdom as it was c.1066, I present to you another potted history for your delectation, this time focussing on the city of Durham.

Durham Cathedral, standing on the promontory above the River Wear. Construction of the Norman cathedral began in 1093 and was largely complete by the 1130s.

As you’ll be able to see by following the links above, the article on Durham is now one of five exploring some of the key places featured in the Conquest Series. In time I’m hoping to expand Tancred’s England to include not just location entries but also features on other aspects of the world in which the novels are set, and articles on various historical topics connected with 1066, the Normans and Anglo-Saxon England. Feel free to get in touch if you have any ideas that you’d like to share!

Earlier this year I launched a new feature on this website to offer you, my readers, an extra insight into the world of the Conquest Series. Entitled Tancred’s England, the idea is to share with you some of the research that goes into writing the novels, by exploring the history of some of the key locations visited by Tancred in the course of his saga.

View over River Teme valley, from Offa’s Dyke Path, north of Knighton.

It’s a part of Britain that’s particularly rich in history, much of which can be freely accessed today. Ancient hill-forts, ruined castles and abbeys all abound, while for 64 miles the great Anglo-Saxon earthwork known as Offa’s Dyke cuts across this striking landscape. Named after the eighth-century Mercian king who is traditionally thought to have ordered its construction, the Dyke delineated the default boundary between England and Wales throughout much of the Middle Ages, and even after 1,200 years it remains a powerful symbol of Offa’s authority.

The cover for the US edition of

The Splintered Kingdom, due to be published by Sourcebooks Landmark

on August 5th, 2014.

I’ll be adding more entries in due course. One of those in the pipeline is about the city of Durham, where Tancred’s tale begins on that cold winter’s night in January 1069. As always, if you have any suggestions for places I could feature in future, please don’t hesitate to get in touch via the contact form.

Knights of the Hawk • James Aitcheson

Arrow • Paperback • £6.99

A year on from the end of The Splintered Kingdom, Tancred is more driven and ambitious than ever. In this, the third instalment in his saga, he casts off some of the shackles binding him and strikes out on his own. Opening during the siege of Ely, where the infamous English outlaw Hereward the Wake has gathered a band of rebels to make one final, last-ditch stand against the Normans, Knights sees Tancred journeying overseas for the first time in the series.

Together with a host of unlikely allies, he sets out on a journey that will take him from the marshes of East Anglia into the wild, storm-tossed seas of the north, as he ventures in pursuit of love, of honour, and of vengeance. Just as in the previous two novels, battles and betrayals abound, but this time it’s personal.

Knights of the Hawk is available from all good high street bookshops and online, and also as an ebook for all major formats of readers. To celebrate the paperback release, I have a number of events lined up, with more being added to the calendar all the time, so keep checking back to see if I’ll be making an appearance in your area soon.

Ely, where Hereward the Wake and his allies made their

stand against the Normans in 1071, and where

Knights of the Hawk begins.

You can also find an entry on Ely and the Fens in my new website feature, Tancred’s England, if you’re interested in finding out more about the setting for Tancred’s latest adventure. As a special web-only bonus, I’ve included a map of how the area would have looked in the Middle Ages before the marshes were drained. There wasn’t space to include it in the book, but I think helps to illustrate the difficult nature of the terrain facing the Normans as they laid siege to Hereward’s island stronghold.

Knights of the Hawk • James Aitcheson

Arrow • Paperback • £6.99

Knights, the third novel in the Conquest Series, which is due to be published in paperback in the UK on Thursday 22nd May, sees Tancred journeying further afield than ever before, setting out across the length and breadth of Britain and making common cause with some unlikely allies as he strives for honour, vengeance and love.

Set in the autumn of 1071, Knights of the Hawk begins during the siege of the Isle of Ely, where the infamous English outlaw Hereward the Wake has gathered a band of rebels to make one final, last-ditch stand against the Normans. As King William’s attempts to assault the rebels’ island stronghold end in disaster, however, the campaign begins to stall. With morale in camp failing, the king turns to Tancred to deliver the victory that will crush the rebels once and for all and bring England firmly within his grasp. But events are conspiring against Tancred, and soon he stands to lose everything he has fought so hard to gain.

Look out for it appearing in a bookshop or a supermarket near you. As always, e-book editions are available on all platforms for the more technologically inclined. If you can’t wait until publication day to get a taste of what’s in store, you can read an extract from the beginning of the book.

And if you’re interested in finding out more about the setting and how the landscape might have looked at the time of the Norman Conquest, there’s an entry on Ely and the Fens in “Tancred’s England”, my historical guide to the kingdom c.1066. Don’t worry, there are no spoilers! As a special web-only bonus, there’s also a map of how the area would have looked in the Middle Ages before the marshes were drained, which unfortunately there wasn’t space to include in the book.

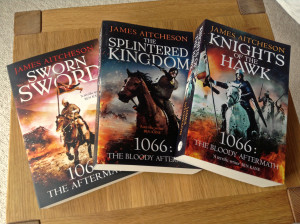

All three books (so far) in the Conquest Series:

UK paperback editions.

Readers in the US unfortunately have a little longer to wait before Knights is available, but in the meantime there’s The Splintered Kingdom to look forward to. Set in the borderlands between England and Wales, it’ll be published this August, and I’ll be revealing more about it in the coming months. Watch this space!

On this week’s edition of In Our Time, the long-running BBC Radio 4 series, the topic under discussion was Domesday Book. One of the most significant documents in English history, it is unparalleled in form and scope, and one of the greatest legacies of the Norman Conquest.

Commissioned by William the Conqueror in 1085, it is, in essence, a kingdom-wide record of who held what estates and other assets in England and how much they were all worth. The level of detail sought by the men carrying out the inquest was remarkable, even if not all of it necessarily made it into the final, edited version. As one of our key sources for the period, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, comments in its entry describing the Domesday Survey:

“…there was not one single hide, not one yard of land, not even (it is shameful to tell – but it seemed no shame for him to do it) one ox, not one cow, not one pig was left out, that was not set down in his [King William’s] record.”

Joining Melvyn Bragg to discuss Domesday Book, the circumstances of its creation, the processes of the survey that supplied the information, its contents and its lasting impact, were three eminent scholars of the Norman Conquest: Elisabeth van Houts, David Bates and Stephen Baxter. It’s a fascinating debate; even after 900 years there remain several unanswered questions as to how it was put together and the exact reason for its being commissioned.

If you missed it, you can catch up online or else download the discussion as a podcast to listen to later from the BBC website. The In Our Time archive includes many excellent programmes related to Anglo-Saxon England and the Norman Conquest, and indeed history in general. In time I plan to compile a list of the best ones and post the links here on the website for anyone who’s interested in finding out more.

For the moment, however, here are two of my favourite programmes from the archives: firstly, Alfred and the Battle of Edington, about the West Saxon king’s struggles against the Viking invaders; and secondly, if you’re looking for further insight into life in England post-1066, The Norman Yoke, exploring and questioning the idea that the Conquest was necessarily a Bad Thing that resulted in many years of harsh oppression for the Anglo-Saxons.

If you’re interested in looking deeper into Domesday Book, meanwhile, or in exploring the history of your own home town or village, you need go no further than the Open Domesday project. Combining map data with records from the survey, it’s a visual, searchable database of who held what property in England, both on the eve of the Conquest in 1066 and at the time of the survey two decades later. It’s free to access, and easy to use.

And of course I can’t talk about Domesday Book and go without mentioning my own grand historical survey of the kingdom of England c.1066, Tancred’s England. With just three location entries so far, it’s not quite on the scale of that eleventh-century masterwork, which records 13,418 places and contains over 2 million words, but I’ll be adding to it bit by bit over the coming months. Any comments, including suggestions for other places that I could feature in Tancred’s England, are welcome – just let me know via the Contact page.