Why is there no historical note in The Harrowing? A number of readers have asked me this over the past two-and-a-half years since the novel was first published. It’s a question that, I’ve come to realise, goes to the heart of what I believe historical fiction is all about. In this post I’ll explore my decision not to include a note (no, it wasn’t down to laziness) and how this fits into my wider philosophy as regards writing fiction set in the past.

In all three of my Conquest novels, first published in the UK between 2011 and 2013, the final chapter or epilogue is followed by an appendix in which I contextualise the story by exploring the real-life events, cultures and individuals who inspired it. In this very short essay – never more than around 2,000 to 2,500 words, or roughly 5 to 6 pages in the printed book – I would offer an insight into some of my preparatory research and the primary sources I’ve relied upon, deconstruct the novel’s relationship to the historical record, and highlight particular occasions where the truth is uncertain, where I’ve used artistic licence, or where I’ve deliberately introduced a fictional element.

The historical note, or author’s note, or afterword – whatever one wishes to call it – is these days a standard element of the historical novel, especially at the commercial end of the market. It’s my general impression that it’s slightly less common at literary end, although by no means is it unheard of. Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood and Burial Rites by Hannah Kent are two prominent examples of novels containing such a note that spring to mind, being as they are conveniently placed on the shelf above my desk as I write this piece. Needless to say, historical notes vary considerably in length: in the case of Burial Rites, it’s a mere three pages; by contrast, C.J. Sansom concludes his latest Shardlake novel, Tombland, with a 60-page essay.

The key reason why I elected not to write a historical note for The Harrowing was my desire to let the story speak for itself. I won’t give any spoilers here, but suffice it to say that the novel finishes on a touching moment, balanced between optimism and tragedy, and with a complex swirl of emotions in play. It felt appropriate to give the reader space to digest the resolution and decide how they feel about the events described, rather than allow the authorial voice to intrude and puncture the atmosphere. Closing the book with Tova’s words rather than my own felt more respectful towards her, the other characters and the journey they have completed – and on which the reader has followed them.

The end, in this case, really is the end. There is no story beyond the story; the novel’s meaning is not complicated or revised by the addition of an appendix that seeks to provide a broader picture, or that brings the reader back to ‘reality’. Demonstrating the narrative’s historical underpinnings would, in this case, have severely undermined what I was trying to achieve.

After all, my rationale for using fiction rather than non-fiction to explore the Harrying of the North – the devastating campaign that saw the Normans lay waste to vast tracts of northern England during the winter of 1069–70 – was that the bare facts and figures seemed insufficient to convey the true horror of this episode. No first-hand accounts of this event have been handed down to us by its victims; their stories have been lost forever. The only way to give voices back to those people, to make sense of their experience, to see them as individual human beings and to rescue them from being relegated to mere statistics, was through fiction.

For that reason, to fall back at the end of the book upon statistics, dates and sources relating to the Harrying of the North as justification or context for the narrative would have seemed to me like an admission of defeat. It would have diminished the creative process, the act of imagination and the attempt to forge an emotional connection with the past, by implying that the story was not robust enough to stand on its own merits.

Here we come to the crux of the matter. In 2017, in an interview at the Oxford Literary Festival, Hilary Mantel criticised her fellow historical novelists who, in her words, ‘try to burnish their credentials by affixing a bibliography’. She said: ‘You have the authority of the imagination, you have legitimacy. Take it. Do not spend your life in apologetic cringing because you think you are some inferior form of historian. The trades are different but complementary.’

The historical note, it is true, offers novelists a chance to set the record straight. In it we can demonstrate the breadth and depth of our reading. In this way, we are arguing for the right to be taken seriously – a natural impulse. But by doing so we are actually asking to be judged by the standards of a different discipline, and so inadvertently diminishing our own status as writers. It is a defensive act rather than a positive statement of our own distinct and legitimate authority.

Novelists, it should go without saying, are not historians. Historical fiction, no matter how well researched, is not history. Its value as a literary genre lies elsewhere. Where? Well, that’s a weighty subject in its own right, and one that I’ll save for another day and another blog post. Suffice it to say for now that historical fiction is the product of a different set of skills, and it is those skills – the craft and technique that we have each developed as writers – that we should be celebrating and drawing particular attention to.

Historians and other scholars are required to show their workings if they are to build a convincing argument. For artists it is different: what matters above all is the final piece. I would much rather these days that my work speaks directly to the reader. That’s why, for me, the historical note has become redundant: not because I have nothing to say, but because to say it would risk dispelling the magic. Yes, it’s always fun to see how the trick is done, but we revel more in the mystery. Less, as so often, is more.

For both narrative and philosophical reasons, then, there is no historical note in The Harrowing. Will there be one in my current work-in-progress? Probably not. That’s not to say I can’t envisage a future novel that might be enhanced by such a note. For now, though, I’m content to keep separate my twin identities – the novelist and the medievalist – and to let them work freely and independently in their own respective ways.

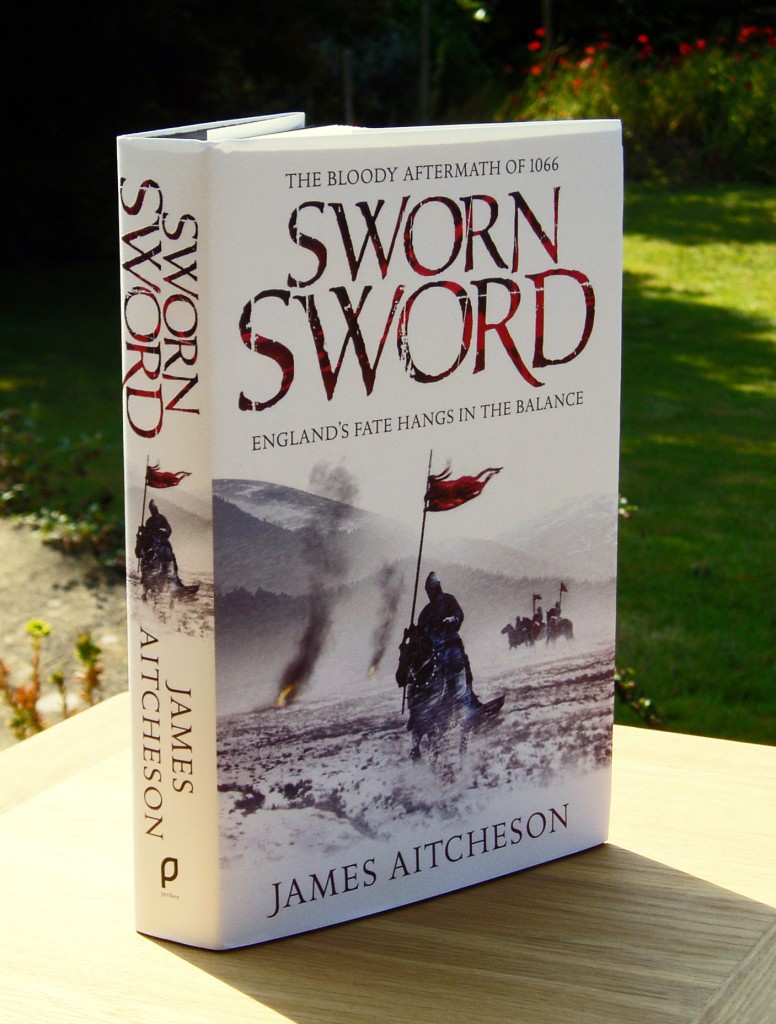

It’s hard to believe, but last month marked the fifth anniversary of the publication of Sworn Sword. My debut novel and the opening instalment in the Conquest trilogy, it arrived in bookshops across the UK for the first time on 4 August 2011.

Where has all that time gone? It seems like only yesterday that I was a wide-eyed young author preparing to release his first work of fiction into the wild, with little experience of literary festivals, book signings or radio interviews and everything else that comes with promoting a book, or indeed much knowledge of the publishing world in general.

My personal copy of Sworn Sword, seen here in pristine condition in August 2011. Nowadays it looks very well-travelled, having accompanied me to many events over the last few years!

Five years on, having just come back from chairing a masterclass on point of view in historical fiction at the Historical Novel Society’s biennial UK conference in Oxford, I realise not only how much I’ve grown as a public speaker, a perfomer and a teacher, passing on my wisdom and hard-won experience – but most especially how far I’ve travelled as a writer.

Four published novels, each very different to the one before it, sometimes in ways that might not necessarily be obvious to the reader, but which to me as the creator are very clear. Around 600,000 words in total, and that’s not including the many revisions, deleted chapters, alternate endings and discarded drafts that never made it into print, nor the pages upon pages of handwritten outlines, character sketches, diagrams or research notes.

And then there’s The Harrowing. I’m proud of all my books, but I’m proudest of this one, partly because it’s the kind of novel that I’ve always longed to write, but mainly because I feel it represents better than any of my other works the full extent of what I have to offer as a novelist. Of that five year period since 2011, more than half my time has been spent on this one project: researching, drafting, redrafting, re-redrafting, editing, polishing, perfecting.

I’ve adapted and in some aspects entirely reinvented my writing style, learnt to write in different voices, played around with unfamiliar narrative structures and devices, generally challenged myself to do things that I’d never attempted before, and (I believe) emerged from the experience a more complete writer.

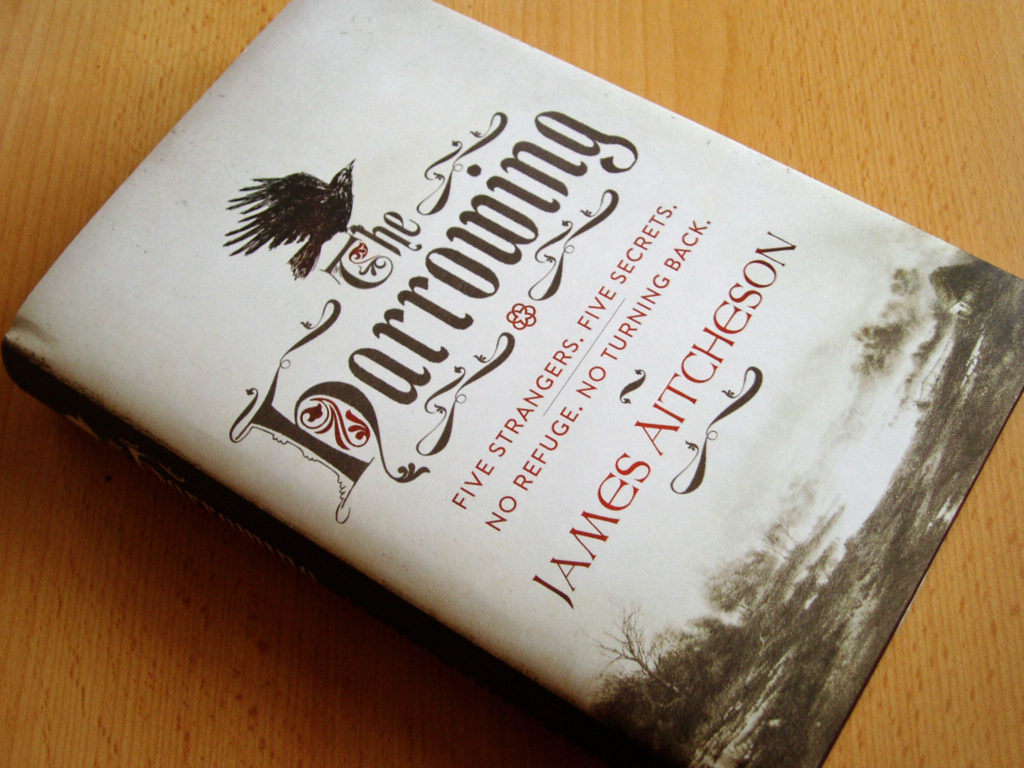

My personal copy of The Harrowing, still looking in good condition – for now!

So thank you, readers, for your loyalty and your continued support over the last few years, for following me on Facebook and on Twitter, for reading my blog and listening to my podcasts, for turning out to hear me speak at events up and down the country, and for buying each new book that’s released and thereby following me on this exciting and most rewarding creative journey.

Last year the novelist Joanne Harris presented her writer’s manifesto, making twelve promises to her readers. In a similar way, I’d like to end this blog post by outlining my personal writing philosophy and make some pledges of my own for the next five years and beyond, namely:

- to seek new ways of reaching out to my readers and providing you with insights into my writing process;

- to continue challenging myself both technically and creatively;

- to explore alternative, sometimes unconventional perspectives, as well as different narrative forms;

- to innovate in historical fiction and push the boundaries of what the genre can do;

- never to be afraid of going against the current or of breaking conventions in the name of originality;

- ultimately, to create something the likes of which has never been seen before.

Here’s to the future, and all that it may bring!

Today’s the day that The Harrowing is officially released into the big, wide world! Almost three years have passed since I first began working on it, so to see it finally in bookshops is hugely exciting.

Signed copies of The Harrowing in the London Review Bookshop.

I’d like to take the opportunity to thank everyone at Quercus Publishing who has worked on the novel over the course of its long journey from manuscript to finished product, including my editors Jon Watt and Stefanie Bierwerth, as well as Kathryn Taussig, Olivia Mead and Jeska Lyons, whose hard work has been invaluable.

Signed copies of the book are already available in several bookshops across central London, including but not limited to Foyles, Waterstones Piccadilly, Goldsboro Books and the London Review Bookshop. I’ll be continuing my book tour over the coming weeks with events across the country.

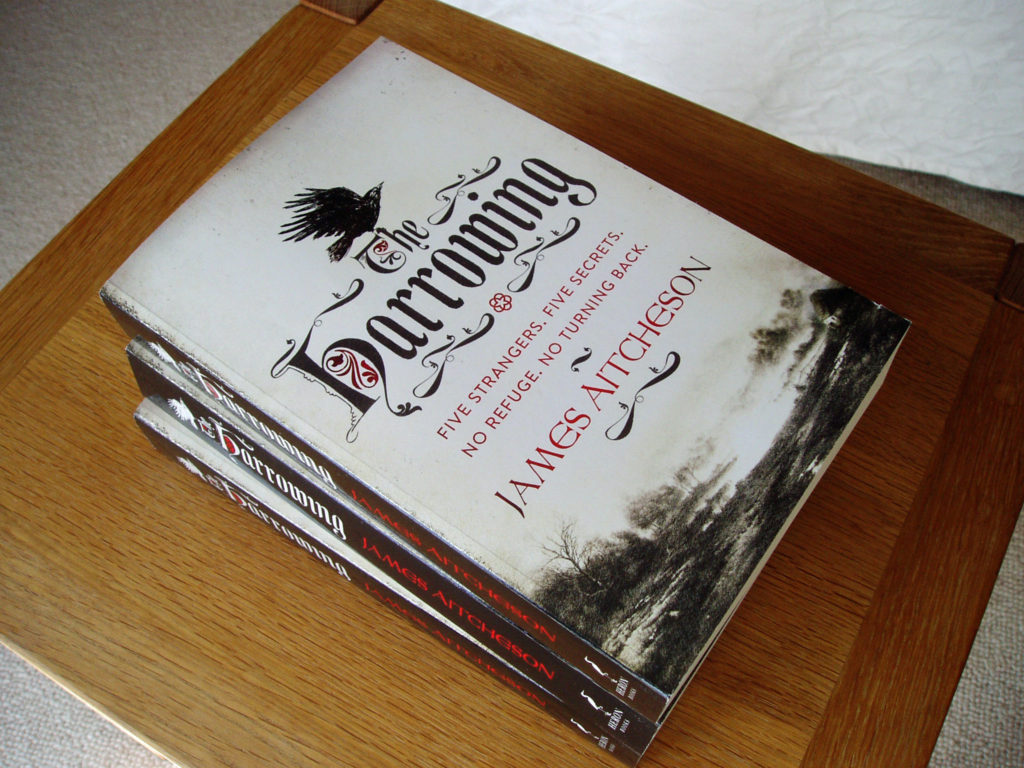

A stack of 100 signed copies of The Harrowing in Goldsboro Books

The Harrowing is also available online through all the usual retailers, and of course is published in digital formats as well to meet your e-reading needs. If you’re based outside the UK and would like to get your hands on a copy, I recommend ordering from the Book Depository, which is based in England but offers free worldwide delivery.

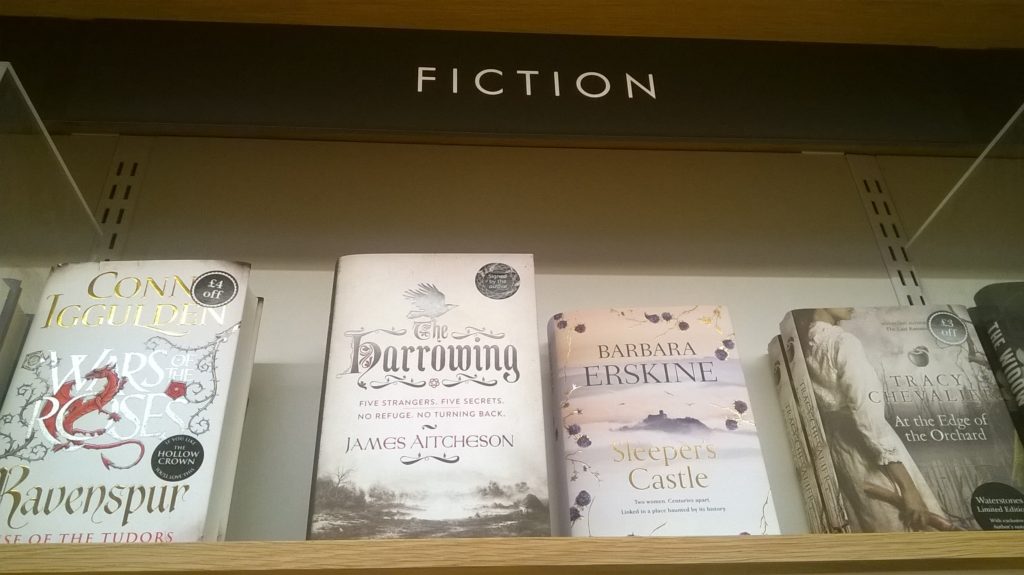

The Harrowing prominently displayed in the hardback fiction section at Waterstones Piccadilly.

I hope you enjoy reading The Harrowing as much as I’ve enjoyed writing it, and I look forward to hearing your comments and feedback over the coming weeks and months! Feel free to get in touch with me at any time, either by emailing me via the Contact page, or through Facebook and Twitter.

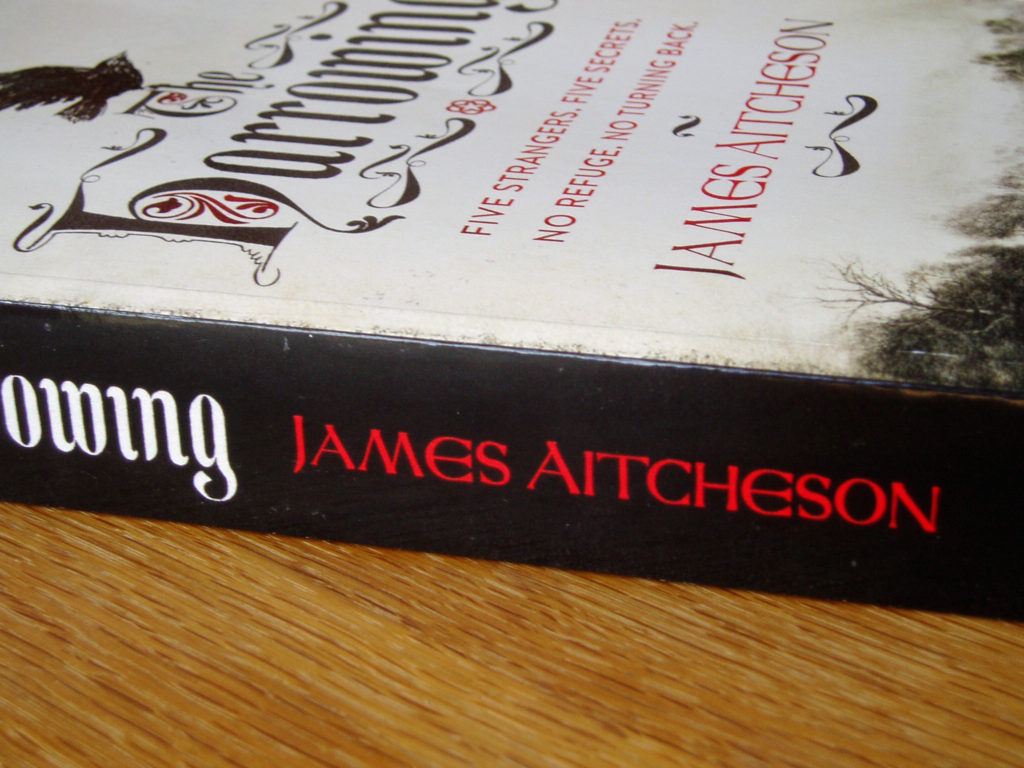

Those of you reading this who follow me on Facebook and Twitter will most likely have already seen the pictures that I posted recently of the finished hardback edition of The Harrowing, which will very soon be published by Heron Books.

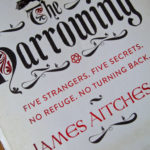

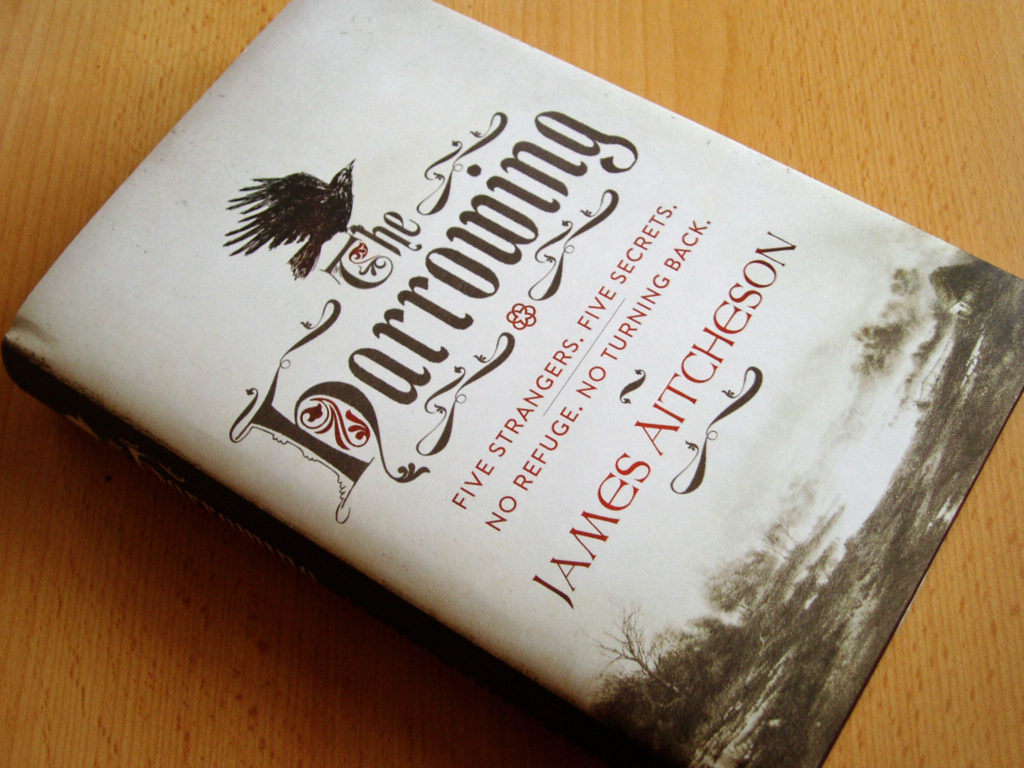

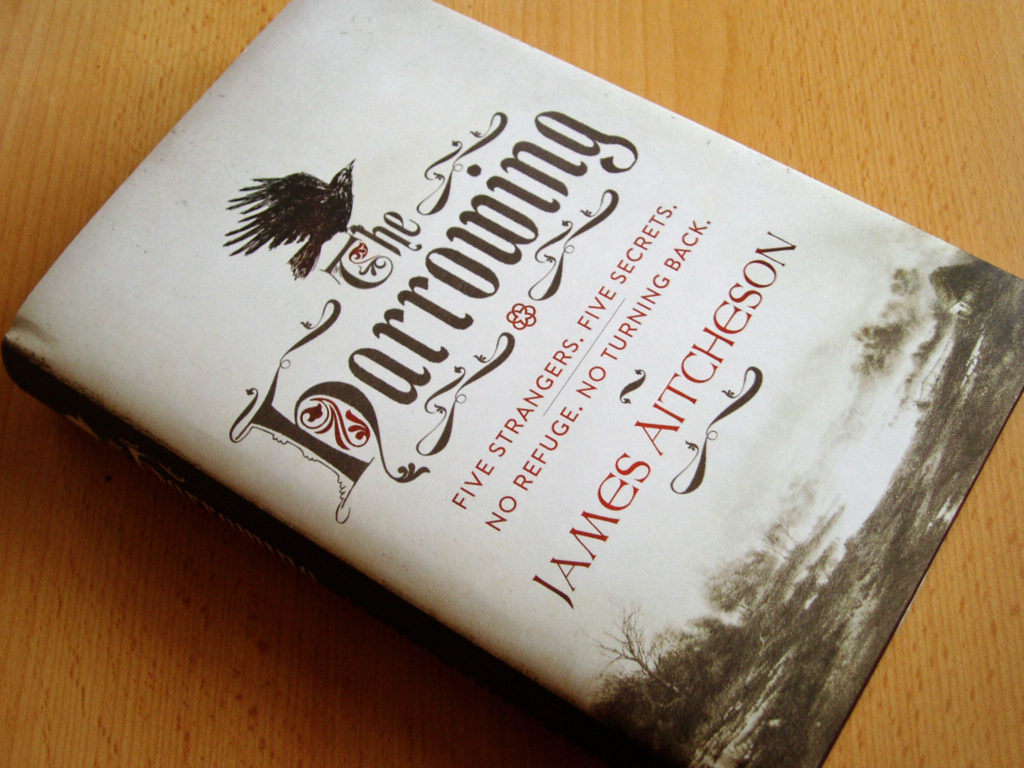

For those who haven’t glimpsed it yet, however, here it is in all its splendour:

The hardback edition of The Harrowing.

As you can see, the jacket design is quite different to those for my Conquest Series, but I feel that it fits the mood of the novel perfectly. In fact I fell in love with the design from the moment I first saw it, and the final product lives up to my expectations in every way possible.

To see this ambitious project come to fruition and to be able to hold the finished book in my hands – nearly three years after I first began work on it and knowing just how many hours’ work is represented in those pages – generates feelings that are difficult to put into words.

Even more exciting is knowing that in just a little over two weeks on Thursday 7 July, this fine tome will appear in bookshops up and down the country. (If you haven’t already done so, you can pre-order your copy either online or from your favourite high street bookshop so that it arrives on the very day that it’s published.)

The title page, where I’ll be placing my autograph at the many book signings and other events coming up in the next few months.

My events calendar for the summer and autumn is taking shape nicely, with signings and talks planned so far in Nottingham, Bath, Cambridge, Oxford, Marlborough, Newbury and Croydon among other places, and more dates to be announced soon.

If I’m not yet scheduled to appear at a venue near you, please do get in touch with your local bookshop or library and ask them if they can invite me to come and do an event.

Always eager to find new ways to connect with my readers, this week I’m launching my official podcast channel on SoundCloud. In my first podcast I talk about my new novel The Harrowing, which is due to be published in the UK in July (Heron, £16.99).

In the coming weeks and months I’ll also be discussing some of the history behind my novels, including the infamous Harrying of the North, which is the subject of The Harrowing.

I’ll also be talking about this year’s 950th anniversary of the Battle of Hastings, and about the third volume in my Conquest Series, Knights of the Hawk, which is due to be published in the US in paperback format in August (Sourcebooks Landmark, $15.99).

Stay tuned for further podcasting adventures!

The first printed copies of The Harrowing arrived in the post recently, courtesy of my excellent publisher Heron Books, to my immense delight. But this isn’t the finished edition of the book; these are what are known as bound proofs, also sometimes called advance review (or reading) copies (ARCs).

Bound proofs (ARCs) of The Harrowing.

The bound proof is the first time that the author gets to see his or her words on the page, and as such it’s an exciting moment: a preview of how the final article will look. It has a soft cover, whereas the edition that will be hitting bookshops in July will be a hardback, and the text inside doesn’t necessarily bear the author’s final changes, but the typesetting and binding are otherwise exactly as they will appear in the published version.

There’s no doubt as to who the author of this fine tome is!

So if you haven’t already done so, mark Thursday 7 July in your calendar. If you’re super-keen to read the novel as soon as it’s published, you can already pre-order your copy either online or from your favourite local bookshop.

I’m also starting to put together my calendar of talks and book signings for this summer and autumn. As always, check my Events page to see if I’m appearing at a venue near you. If not, please do get in touch with your local bookshop or library and ask them if they can invite me to come and speak.

Keep a look out for more news on The Harrowing in the coming weeks. For now, here’s one final photo to whet your appetite. And so it begins…

Here’s what it looks like on the inside.