One of the toughest challenges involved in writing about medieval warfare is that of describing what battle in that period was like: how it might have felt to be there, including not just the physical sensations but also the psychological and emotional. What would have been running through the combatants’ minds? What motivated and inspired men like my protagonist, Tancred, to take up arms in the first place, and what gave them the confidence to risk their lives in the fray? Was it for money or fame that they principally fought, in the name of God or one’s king, or (more probably) was it a combination of all of these things?

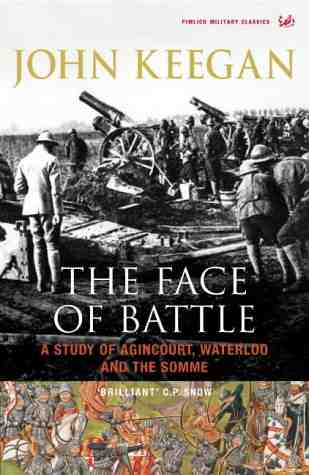

The historian John Keegan, who sadly passed away last year, explores similar themes in his pioneering book The Face of Battle, in which he analyses and compares the experience of combat in three major encounters of the last 600 years: Agincourt (1415), Waterloo (1815) and the Somme (1916). In particular he examines how the mechanics and logistics of conflict affected the psychology of the individual soldier – looking not just at the critical moments during the heat of combat, but also at the hours before battle was joined, and its aftermath once the dust has settled.

The historian John Keegan, who sadly passed away last year, explores similar themes in his pioneering book The Face of Battle, in which he analyses and compares the experience of combat in three major encounters of the last 600 years: Agincourt (1415), Waterloo (1815) and the Somme (1916). In particular he examines how the mechanics and logistics of conflict affected the psychology of the individual soldier – looking not just at the critical moments during the heat of combat, but also at the hours before battle was joined, and its aftermath once the dust has settled.

Keegan eschews analyses of strategy and tactics that many conventional military histories often involve, which – he argues – can sometimes misrepresent the ebb and flow of battle; instead he recognises the chaos and unpredictability inherent in war. The focus of his study is statedly not upon the respective generals and their abilities to lead and choose the correct course of action, but upon the lower ranks: a bottom-up rather than a top-down angle.

An advantage, too, of taking such a long view of the experience of battle is that he is able to highlight those aspects that have remained constant even over hundreds of years, in widely different fighting environments; and those which have altered as a result either of technological development – in weaponry, transport and communication, among other areas – or of societal changes.

A good example of the latter is the religiosity of the common soldier, which had declined during the age of the Enlightenment prior to Waterloo, only to re-establish itself in the Victorian age. The motivations of the men fighting in 1815 were thus vastly different to those of their counterparts only a century later. Prayer and faith in God helped many British soldiers combat their fears and reconcile themselves with the possibility of death in 1916, in a way and to an extent that their predecessors at Waterloo would not have been able to identify with, but which those at Agincourt very probably would.

One particularly ingenious feature of the book, which I can’t fail to mention, lies in the maps. Keegan juxtaposes the fields of battle firstly of Agincourt and Waterloo, and then of Waterloo and the Somme, depicting them on the same scale to demonstrate how the magnitude of battle has increased exponentially over the centuries.

Due to the outpouring of fiction in the military-historical sub-genre in the last couple of decades, accounts of past conflict illustrating the hardships and traumas faced by the front-line soldier are much more familiar than they once were. At the same time there has been a massive surge of interest in recent decades into the kind of bottom-up history favoured by Keegan: an interest that began in academia but which has filtered down into popular history as well, so that there has been an explosion in studies of this nature.

For both of those reasons The Face of Battle doesn’t seem quite quite as revolutionary a text as it probably did when it was first published in 1976. Nevertheless, it remains a thoroughly absorbing and eye-opening read, and one that I can highly recommend.

Promotional poster for the Second World War miniseries Band of Brothers, which was originally broadcast in 2001.

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother …

– William Shakespeare, Henry V, Act IV Scene iii

The idea of the “band of brothers” is central to Sworn Sword. The opening encounter at Durham sees Tancred’s conroi (the basic Norman cavalry unit, usually composed of around twenty men) shattered and his lord killed at the hands of Northumbrian rebels. Only two of his fellow knights, his close friends Eudo and Wace, survive to help him carry the stain of that defeat. The close group of warriors he once belonged to, who ate and trained and joked and fought together, is no more.

What happened to the real survivors of Durham is not recorded in the primary sources that mention the battle; indeed it is rare that the chronicles offer much by way of insight into the feelings of the people whose fates they record. Still, it is possible to imagine the grief and guilt and sense of loss those survivors had to bear, and the thoughts of revenge they must have harboured.

To capture a full sense of what it means to be part of such a tight-knit combat unit, I sometimes look to similar depictions elsewhere in fiction. One of the best portrayals I’ve come across is in the TV miniseries Band of Brothers. I first saw this series when it was originally shown in 2001, and watched it a second time a few years back when I was in the early stages of writing the novel that would become Sworn Sword.

With the second book, The Splintered Kingdom, now completed and my thoughts already turning to the next instalment of Tancred’s story, I went back to view the series on DVD again this week. Each time I’ve come to it with new eyes, and each time I’ve been able to take something away from it that either adds to my understanding of the hardships of war, or gives me ideas for fresh avenues to explore or new ways to depict the ongoing conflict that was the Norman Conquest in my writing.

The “band of brothers” of the series’ title is Easy Company of 2nd Battalion, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment in the 101st Airborne Division of the U.S. Army. Over ten episodes we follow the exploits of the various characters – all based on real-life individuals – who make up the company, from their early training to Operation Overlord, and from there through Operation Market Garden and the Battle of the Bulge to the occupation of Germany at the end of the war.

The over-arching narrative of the 1944-5 campaign in Western Europe bears some similarities to that of the Norman Conquest. The series of operations which led from the Normandy landings to Berlin was long and arduous; progress was sporadic and frequently subject to German counter-offensives. Just as D-Day was only the beginning in June 1944, so the Battle of Hastings proved merely the opening engagement, albeit a highly significant one, in the Conquest.

Even though nearly 900 years separate the Second World War from my own period, there’s still a lot that can be learnt from Band of Brothers, not least regarding the experience of war and the psychology of those individuals who make it their business to fight. It’s fascinating to follow the journeys of the various characters and see how they each respond to the situations they find themselves in, and face up to challenges both physical and emotional.

We see green and untested volunteers develop into seasoned and skilled campaigners. Some appear to be natural warriors and born leaders, and find themselves in their element from the start, while others take time to find their feet. Some are strengthened by their experience of the war; others find themselves consumed by it, to the point where in order to make it through they sacrifice some of their humanity. One thing they have in common is that they are all changed by what they have seen and done.

War exacts its toll upon the individual in different ways, as I hope The Splintered Kingdom will show. As the battle for England intensifies and the kingdom falls under siege on all sides, the Normans’ grip on their hard-fought gains grows ever weaker, and in the middle of the struggle Tancred finds his resolve put to the test as never before.