This week I’ll be writing what I hope will be the final scene of my latest novel – the first draft typescript is pictured below. With that in mind, I thought it would be the perfect time to reflect upon what reaching ‘The End’ means to me, to share some of my experiences and to offer some tips.

Firstly, getting to the end is rarely as dramatic or as definite a moment as is often popularly imagined. You can forget those film montages in which the writer types furiously through the night until, with the sun coming up, he gives a huge, contented sigh and types those two simple yet immortal words. This perfect moment of elation, exhaustion and fulfilment might look good on screen, but it hardly ever happens in real life.

Sometimes, it’s true, I do attack that final scene in a mad rush, but not always. Often it must be approached slowly, paragraph by paragraph, over several days. If you come at it too quickly, you risk scaring it off.

Sometimes you don’t even know you’ve reached the last sentence until you get there. It can catch you by surprise: you find yourself typing a sequence of words that you never intended but which just feel right.

At other times you know exactly the final phrase that you want to arrive at – maybe you’ve known for months already. In that case it’s especially important not to rush, but to work methodically and carefully. The End still has to be earned.

The joy of finishing can be short-lived. My experience is often one of anticlimax. I say to myself, ‘What now?’

A case in point is my second novel, The Splintered Kingdom. The words were flowing so quickly, so beautifully and easily and I felt so ‘in the zone’ that, after I’d typed that last sentence, I didn’t know what to do with myself. It was like coming back down from 200mph to a standstill in the blink of an eye. I had so much adrenaline that I desperately wanted to keep writing. But I had nothing more to say.

For these reasons, typing your final sentence isn’t always as satisfying as you feel it ought to be. What I’ve come to realise, after writing five novels, is that this is entirely normal. I no longer worry about it.

Pro tip #1: it’s about the journey, not the destination.

Another reason why The End isn’t necessarily as fulfilling as you might hope is that sometimes it turns out not to be The End after all. You can be in the middle of writing it when you realise it’s not quite what you had in mind. It’s perfectly okay to put in something provisional: a placeholder that will serve until a better idea comes along.

If this happens, it’s possible there’s a problem elsewhere in the story, or something as yet unresolved. Look for what might be missing: it’s possible that some final understanding or inner growth is still required on the part of your protagonist, for example. Resolve it. Then try again.

Pro tip #2: things rarely come out perfect first time.

You don’t have to write the whole thing in one go. What I call my ‘first draft’ sometimes only contains the first 90% or so of the novel. I add the ending later, after reading through the whole thing and giving it a thorough edit, once I’m sure of the direction of travel. This happened with my current work-in-progress. (The ‘first draft’ typescript pictured above is, in fact, incomplete.)

It’s crucial to stress, too, that The End is never the actual end of the process. Despite what those film montages might suggest, the writer still has work to do before his novel is finished: redrafts to do, edits to make, early reader feedback to take into account. He’s close, but he’s not quite there yet.

To summarise: although writing that final sentence and completing a draft is something to celebrate, for me it somehow never quite turns out to be the big moment that people seem to imagine it is. It’s just another stage in the process.

And it should go without saying, of course, that you don’t have to actually type the words ‘The End’. Others might disagree, but I find it old-fashioned and unnecessary in most cases.

In most cases. In this one I’ll make an exception.

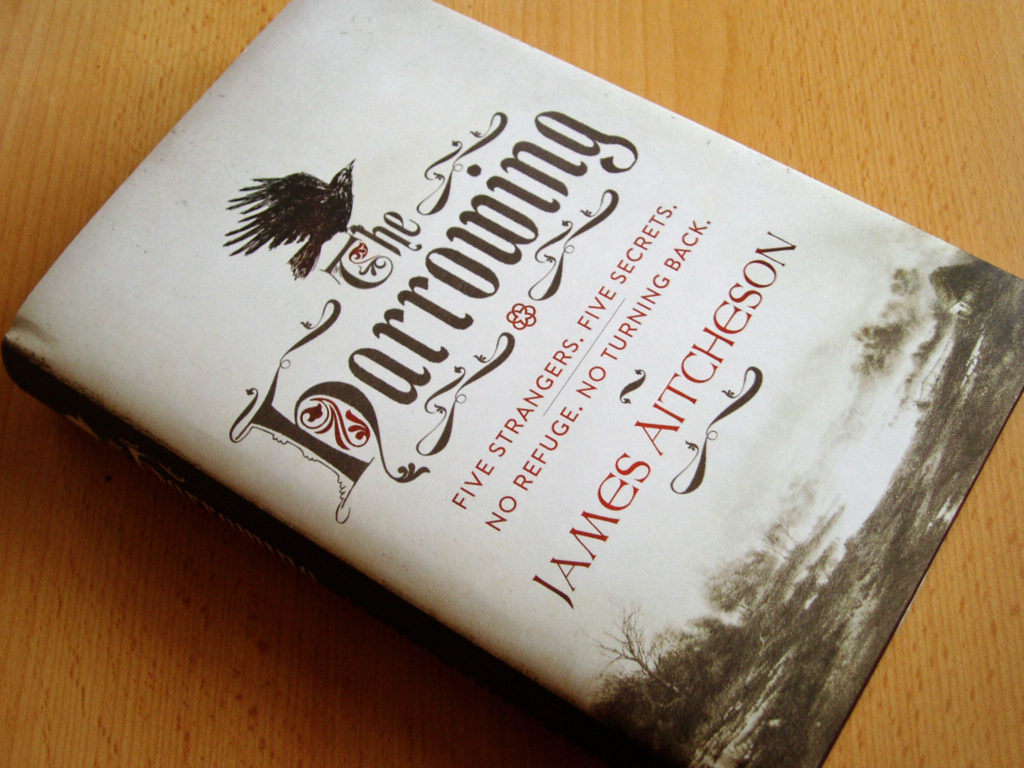

Why is there no historical note in The Harrowing? A number of readers have asked me this over the past two-and-a-half years since the novel was first published. It’s a question that, I’ve come to realise, goes to the heart of what I believe historical fiction is all about. In this post I’ll explore my decision not to include a note (no, it wasn’t down to laziness) and how this fits into my wider philosophy as regards writing fiction set in the past.

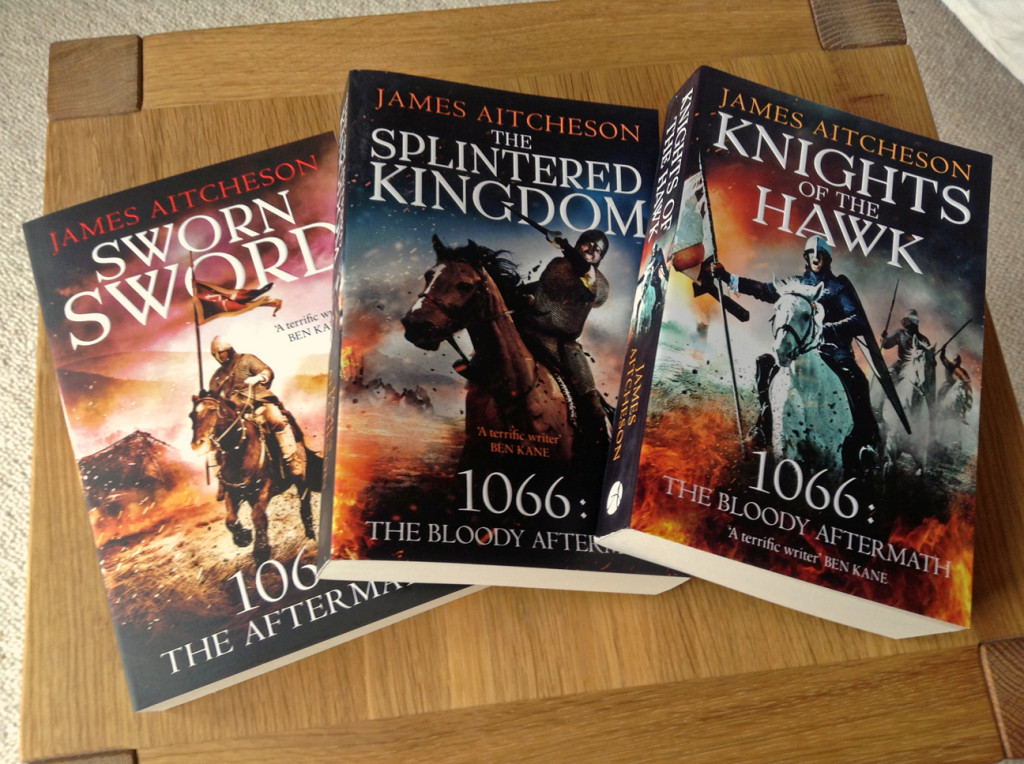

In all three of my Conquest novels, first published in the UK between 2011 and 2013, the final chapter or epilogue is followed by an appendix in which I contextualise the story by exploring the real-life events, cultures and individuals who inspired it. In this very short essay – never more than around 2,000 to 2,500 words, or roughly 5 to 6 pages in the printed book – I would offer an insight into some of my preparatory research and the primary sources I’ve relied upon, deconstruct the novel’s relationship to the historical record, and highlight particular occasions where the truth is uncertain, where I’ve used artistic licence, or where I’ve deliberately introduced a fictional element.

The historical note, or author’s note, or afterword – whatever one wishes to call it – is these days a standard element of the historical novel, especially at the commercial end of the market. It’s my general impression that it’s slightly less common at literary end, although by no means is it unheard of. Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood and Burial Rites by Hannah Kent are two prominent examples of novels containing such a note that spring to mind, being as they are conveniently placed on the shelf above my desk as I write this piece. Needless to say, historical notes vary considerably in length: in the case of Burial Rites, it’s a mere three pages; by contrast, C.J. Sansom concludes his latest Shardlake novel, Tombland, with a 60-page essay.

The key reason why I elected not to write a historical note for The Harrowing was my desire to let the story speak for itself. I won’t give any spoilers here, but suffice it to say that the novel finishes on a touching moment, balanced between optimism and tragedy, and with a complex swirl of emotions in play. It felt appropriate to give the reader space to digest the resolution and decide how they feel about the events described, rather than allow the authorial voice to intrude and puncture the atmosphere. Closing the book with Tova’s words rather than my own felt more respectful towards her, the other characters and the journey they have completed – and on which the reader has followed them.

The end, in this case, really is the end. There is no story beyond the story; the novel’s meaning is not complicated or revised by the addition of an appendix that seeks to provide a broader picture, or that brings the reader back to ‘reality’. Demonstrating the narrative’s historical underpinnings would, in this case, have severely undermined what I was trying to achieve.

After all, my rationale for using fiction rather than non-fiction to explore the Harrying of the North – the devastating campaign that saw the Normans lay waste to vast tracts of northern England during the winter of 1069–70 – was that the bare facts and figures seemed insufficient to convey the true horror of this episode. No first-hand accounts of this event have been handed down to us by its victims; their stories have been lost forever. The only way to give voices back to those people, to make sense of their experience, to see them as individual human beings and to rescue them from being relegated to mere statistics, was through fiction.

For that reason, to fall back at the end of the book upon statistics, dates and sources relating to the Harrying of the North as justification or context for the narrative would have seemed to me like an admission of defeat. It would have diminished the creative process, the act of imagination and the attempt to forge an emotional connection with the past, by implying that the story was not robust enough to stand on its own merits.

Here we come to the crux of the matter. In 2017, in an interview at the Oxford Literary Festival, Hilary Mantel criticised her fellow historical novelists who, in her words, ‘try to burnish their credentials by affixing a bibliography’. She said: ‘You have the authority of the imagination, you have legitimacy. Take it. Do not spend your life in apologetic cringing because you think you are some inferior form of historian. The trades are different but complementary.’

The historical note, it is true, offers novelists a chance to set the record straight. In it we can demonstrate the breadth and depth of our reading. In this way, we are arguing for the right to be taken seriously – a natural impulse. But by doing so we are actually asking to be judged by the standards of a different discipline, and so inadvertently diminishing our own status as writers. It is a defensive act rather than a positive statement of our own distinct and legitimate authority.

Novelists, it should go without saying, are not historians. Historical fiction, no matter how well researched, is not history. Its value as a literary genre lies elsewhere. Where? Well, that’s a weighty subject in its own right, and one that I’ll save for another day and another blog post. Suffice it to say for now that historical fiction is the product of a different set of skills, and it is those skills – the craft and technique that we have each developed as writers – that we should be celebrating and drawing particular attention to.

Historians and other scholars are required to show their workings if they are to build a convincing argument. For artists it is different: what matters above all is the final piece. I would much rather these days that my work speaks directly to the reader. That’s why, for me, the historical note has become redundant: not because I have nothing to say, but because to say it would risk dispelling the magic. Yes, it’s always fun to see how the trick is done, but we revel more in the mystery. Less, as so often, is more.

For both narrative and philosophical reasons, then, there is no historical note in The Harrowing. Will there be one in my current work-in-progress? Probably not. That’s not to say I can’t envisage a future novel that might be enhanced by such a note. For now, though, I’m content to keep separate my twin identities – the novelist and the medievalist – and to let them work freely and independently in their own respective ways.